View more information about the North American Pipeline Map

Background Information about the Rogersville Shale

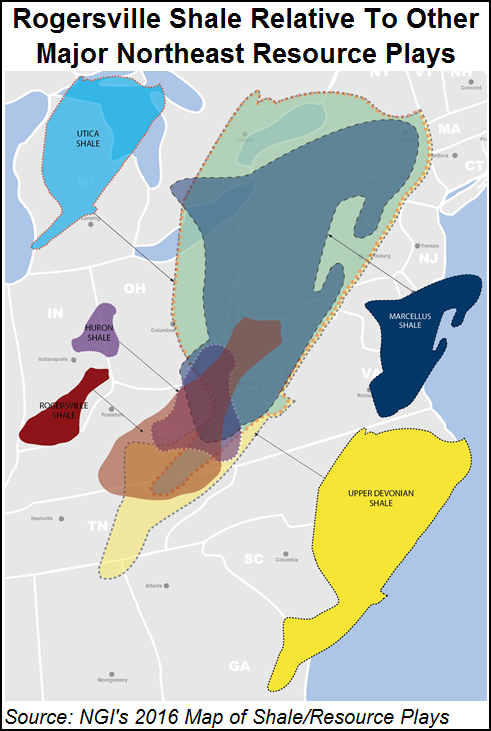

Located in a deep sub-basin known as the Rome Trough, the Rogersville Shale is one of six formations in the Conasauga Group, which includes the Pumpkin Valley Shale, Rutledge Limestone, Maryville Limestone, Nolichucky Shale and the Maynardville Limestone. Other shales in the group have tested poorly for hydrocarbons. But there exists a limited body of evidence that suggests the Rogersville could be comparable to the Marcellus and Utica Shales (see Shale Daily, July 24, 2015).

From 1999-2002, researchers at the Kentucky, Ohio and West Virginia Geological Surveys refined the stratigraphic framework of the Rome Trough, which underlies the Appalachian Basin. Furthermore, in a 2005 U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) report that utilized some of the states’ research, and was authored in part by EQT Corp. and the Kentucky Geological Survey (KGS), researchers said the Rogersville is likely the hydrocarbon source rock for producing sandstone reservoirs in the Rome Trough of West Virginia and Kentucky.

Commercial production from the Rome Trough includes the Homer Field in Elliott County, KY, where sandstone reservoirs have produced more than 2 Bcf of natural gas, according to KGS. But the impetus for today’s interest in the Rogersville is based on a series of documented wells drilled to deeper targets in the 1960s and 1970s.

The sub-basin is narrow, extending from Kentucky northeastward into Ohio, Pennsylvania and Southern New York. It remains unclear what it, or other shales in the Conasauga could hold for producers north of West Virginia. The organic rich Rogersville is thought to be confined to Kentucky and West Virginia. At a depth of roughly 9,000-10,000 feet in Kentucky and 12,000-14,000 feet in West Virginia, the formation is essentially no deeper than some Utica wells that have been drilled, making it a conceivable target. It has what KGS says is a “suitable thickness,” ranging from 200 to more than 1,000 feet in both eastern Kentucky and southwestern West Virginia. Moreover, according to the KGS, the Rogersville’s mineralogy, organic content and thermal maturity are all right to produce gas or liquids if “fractured to improve permeability.

“Challenges in developing a Rogersville Shale play include interpreting structure and stratigraphy in the deeper, fault-segmented parts of the Rome Trough and predicting the distribution of organic-rich intervals,” KGS said. “The play concept has been proven, and economic viability will depend on the production rates established and fluid type.”

As of November 2015, six modern Rogersville test locations had been permitted, with all but one of those located in eastern Kentucky’s Lawrence and Johnson counties. Just five test wells had been drilled at the time of this writing. Only one of those was a horizontal well, drilled by EQT Corp. subsidiary Horizontal Energy Technology Inc. in Johnson County. Plans for more sites appear to be on the rise as other stratigraphic permits that omit the operator’s name have been issued in these areas.

Chesapeake Energy Corp. has drilled two vertical Rogersville tests in Lawrence County, while Cabot Oil & Gas Corp.’s No. 50 Amherst Industries vertical Rogersville well in Putnam County, WV, was said by KGS to be producing dry gas to sales in November 2015 (see Shale Daily, Nov. 13, 2015). But Denver-based Cimarex Energy Co., a company that primarily operates in the Permian Basin and Midcontinent, has been a pioneer in the play. Through its subsidiary, Bruin Exploration LLC, the company obtained the first Rogersville permits in 2013 and in 2014. It drilled a vertical test well — the Sylvia Young No. 1 — in Lawrence County.

In August 2015, a completion report released by the Kentucky Division of Oil and Gas showed initial test volumes of only 19 b/d of oil and 115 Mcf/d of natural gas (see Shale Daily, Aug. 20, 2015). It’s unclear for how long the well flowed, but it was drilled to a depth of 11,967 feet and state records show the company has since been issued a horizontal permit to kick the well out. Cimarex also has permitted a second Rogersville well to the south of the Sylvia Young, while Chesapeake has received another horizontal permit for one its test wells in Lawrence County. Head of the Energy and Minerals Section at the KGS David Harris said while Cimarex’s “volumes are modest, the first vertical well may not reflect the potential of the zone.”

None of the larger exploration and production companies that are currently active in the Rogersville have publicly discussed their operations there. But in a 2Q2015 earnings call with financial analysts, Cabot CEO Dan Dinges said the company has nearly one million acres in West Virginia. Although he didn’t provide specifics about any particular formation, he added that the company has ongoing exploration efforts south of Wood County, WV, in the western part of the state, looking at a “deeper section” there. “We’re usually cautious when it comes to discussing exploration efforts…We have a couple areas that we’re continuing to look at that we think have exploratory opportunity anyway,” Dinges said. “…We have enough reason to believe that it merits further capital at some time.”

The viability of the play was proven decades ago. In the mid-1960s, the Inland No. 529 White well drilled in Boyd County, KY, — north of Lawrence County — yielded the first commercial oil production from Cambrian-age rocks in the Rome Trough, producing 10,000 bbl of oil and associated gas from the Maryville Limestone. Another test well drilled to the Maryville in Jackson County, WV — just north of Putnam County — produced natural gas at 6-9 MMcf/d. It was an ExxonMobil Corp. predecessor company that drilled several deep wells in the Rome Trough at the time that revealed more about the Rogersville, coring the formation with its No. 1 Smith well in Wayne County, WV, southwest of Putnam County.

As part of their efforts to refine the Rome Trough’s framework, researchers at the Kentucky, Ohio and West Virginia Geological Surveys analyzed that core. They found that while the total organic content (TOC) of other cores from shales in the Conasauga Group was less than 1%, Exxon’s Rogersville core showed a TOC of nearly 5%.

“A lot of this has been sort of developed off of what was seen in that core, in that old Exxon well,” Harris told NGI. “That was the key evidence that there was organic content and there was also big gas shows when they drilled through that zone. We have those records and mud logs that show potential hydrocarbons in the zone.”

Given the depth of the shale in West Virginia, the industry believes that the Rogersville is likely a dry natural gas play there, while shallower depths in Kentucky are expected to yield both oil and gas. Most agree that Rogersville exploration likely has been impeded by the commodities downturn and while leasing activity slowed heading into the end of 2015, land records show interest among a suite of producers and land brokerage firms. From January 2014 to June 2015, across a three-county stretch in Eastern Kentucky, including Magoffin, Johnson and Lawrence counties, 3,863 leases were signed for the Rogersville, according to data compiled by the mineral management firm Global Natural Resource Management Co., which works in the state. Of those, 2,127 of them were executed in Magoffin County.

At the end of June 2015, land brokerage Gulfland Appalachian Energy Inc. had the most leases with 1,073; EQT had 400; Cimarex had 378; Chesapeake had 105, and land management company Exterra Resources LLC had 466. “I’ve worked in the state since 2002. Cimarex came in in 2012 under the radar with [Gulfland Appalachian] and started the leasing activity in Lawrence County, but didn’t expand into Magoffin until later,” said Global Natural Resource’s Executive Vice President Wesley Cate in a July 2015 interview with NGI. “I would not be surprised if you see the same kind of activity spread into Wolfe, Lee and Estill counties, KY. Just through the rumor mill, I’ve heard there’s already some leasing activity in Lee County.” West Virginia Oil and Natural Gas Association Executive Director Corky DeMarco also has confirmed that joint ventures, farm outs and land deals have been common in southwest West Virginia where the Rogersville is thought to be viable.

With so few drill bits having gone through the Rogersville, there is no reliable resource estimate. As part of work for the Colorado School of Mines’ Potential Gas Agency, a group of Appalachian experts gathered in 2015. They determined that there was not enough information to estimate the resource base adequately, but one official said for now it is “quite small,” adding that it would likely change as more production information is released. That is not likely to happen for a year or more as operators have either have been granted or have asked for confidentiality to protect that information under West Virginia and Kentucky state laws (see Shale Daily, Sept. 23, 2015). The USGS has said it does not have an ongoing assessment of the Rogersville or any personnel with extensive knowledge of its resources or geological characteristics.

Counties/Parishes

Because little is known about the Rogersville’s areal extent and exploration is nascent, prospective counties listed here are based on current activity and historical production.

Kentucky: Boyd, Elliott, Estill, Johnson, Lawrence, Lee, Magoffin, Wolfe

West Virginia: Jackson, Putnam, Wayne

Local Major Pipelines

Natural Gas: Columbia Gas, Columbia Gulf, Dominion, Tennessee

More information about Shale Plays:

Utica | Permian | Bakken | Tuscaloosa Marine Shale | Haynesville | Montney | Arkoma-Woodford | Eastern Canada | Barnett | Cana-Woodford | Eaglebine | Duvernay | Fayettville | Granite Wash | Horn River | Green River Basin | Lower Smackover / Brown Dense Shale | Mississippian Lime | Monterey | Niobrara – DJ Basin | Oklahoma Liquids Play | Marcellus | Eagle Ford | Upper Devonian / Huron | Uinta | San Juan | Power River | Paradox

Shale Daily

Shale Daily