Marcellus | E&P | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report | Utica Shale

Industry Panel Debates Best Way to Get Marcellus/Utica Gas to Northeastern Markets

As natural gas production from the Marcellus and Utica shales in the Northeast continues to soar, the industry faces a delicate balancing act on what types of pipelines or liquefied natural gas (LNG) projects make economic sense to construct in order to get the gas to market, a panel of industry executives said Monday.

The LDC Gas Forum Northeast panel mostly focused on the risks, challenges and opportunities facing the oil and gas industry in the Marcellus and Utica shales, at a time when production is increasing amidst regulatory uncertainty.

Statoil Natural Gas LLC President Jan Rune Schopp told the Boston audience Monday that production in the Marcellus has “gone beyond our wildest expectation, and it’s increasing by the day.” But he cautioned that companies need to look 10-20 years down the road to ensure that any proposed projects make economic sense. For instance, a current moratorium against high-volume hydraulic fracturing in New York may complicate some projects.”

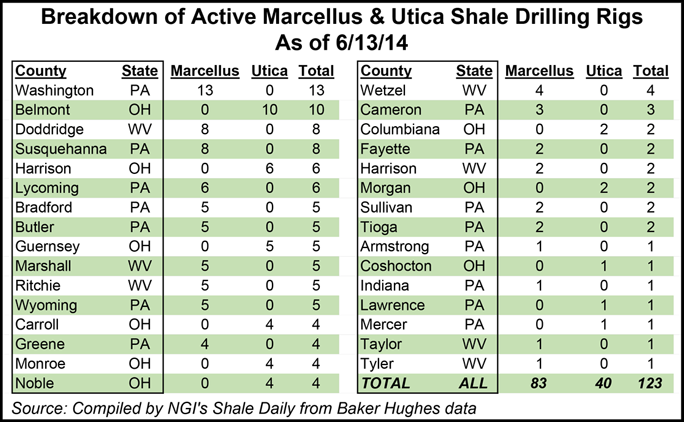

And activity in the Marcellus and Utica shales continues to grow. According to Baker Hughes, as of June 13 there were 83 rigs active in the Marcellus, which marks an 11% increase over the 75 rigs that were in operation one year ago. Similarly, the 40 rigs active in the Utica for the week ending June 13 represents a 21% increase over the 33 rigs active one year ago.

“The entire region in the Northeast is blessed with that resource,” Schopp said. “Whether or not New York is going to do something with the moratorium, I don’t have any opinion on. I just register that the processes are set in place to handle this issue the way New York wants to handle it.

“My biggest concern, aside from ensuring timely infrastructure to move the gas from the Marcellus, is how to get the gas and power markets to work in an efficient manner to provide the correct investment signals so that we can have a balanced fleet of generation.”

GDF Suez Gas NA LLC’s Anthony Scaraggi, vice president of operations, said the main issue facing New England has always been a lack of local natural gas supplies.

“The gas in New England is always going to be tied to transportation between wherever the supply point is and New England,” Scaraggi said. “Getting the gas from where it’s located to us in New England through long-haul pipelines is a very expensive proposition. Whether or not it can done for the various NIMBY [not in my backyard] reasons that we always experience around here is another whole story.

“But that being said, there are a certain series of pipelines that make absolute sense to build, and those are the ones that are economic and bring incremental gas to people who are looking to use gas today, who are just not located close enough to anything.” But there are some long-haul pipes that are just too costly. “They just don’t really make economic sense. The markets themselves would not choose those options.”

He added that it wouldn’t make sense to add liquefaction facilities to GDF Suez facilities in Everett, MA. But LNG could be produced elsewhere, for instance in the Marcellus and Utica shales.

“I don’t think that makes any sense for us in New England,” Scaraggi said of LNG facilities. “There’s really no supply. The only type of liquefiers you have in New England are liquefiers to essentially take any excess gas off the pipeline during times of underutilization, to have it for times of peak utilization.

“The interesting thing about shale gas areas is that you could build liquefiers in the shale gas areas and transport that LNG to any place in the U.S. Now we all know what’s happened recently in Canada with crude oil, so that’s all been kind of slowed down by regulation. But building liquefiers in the U.S., in areas where you would really not normally considered them built, is a realistic thing these days. But not necessarily in New England.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |