Marcellus | E&P | NGI All News Access | Utica Shale

‘Incumbents,’ PE Deals Dominating Appalachian NatGas Consolidation

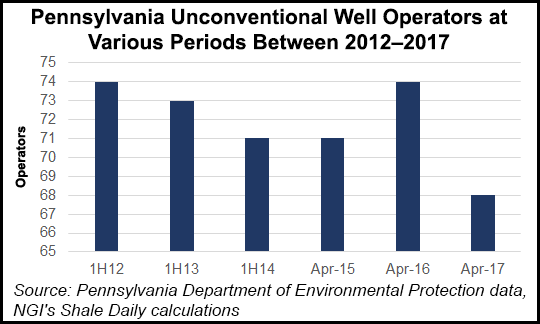

After years of relative inactivity, dealmaking in the Appalachian Basin is once again healthy but tenuous, as the region’s larger natural gas producers and private equity (PE) firms reassert their dominance in a market filled with both opportunities and risks.

Consolidation has accelerated for roughly a year now, culminating on Monday with EQT Corp.’s $8 billion deal to acquire Rice Energy Inc. — a milestone that some agree marks a new era in the basin’s development. It’s unclear when — and how big they’ll be — but there are rumblings of other deals in the works, industry sources said over the last week at a series of conferences in Pittsburgh.

“You definitely see the incumbents dominating the activity…that’s what I see as the next chapter right now,” said Art Krasny, managing director of acquisitions and divestitures at Wells Fargo Securities LLC, during a panel discussion at Hart Energy’s Dug East conference on Wednesday. “I see the incumbents consolidating around the cores and private equity picking up positions that have become noncore for the guys that are exiting and focusing elsewhere. We are kind of at that interesting place in the market where it feels like it’s pivoting right now and we don’t know where it’s going to go.”

Escalating Deals

Since the beginning of 2016, EQT has added 485,000 net acres to its Appalachian-plus portfolio, acquiring Rice, Trans Energy Inc. and Stone Energy Corp.’s Appalachian assets. It also completed another deal last year with global heavyweight Statoil ASA. Antero Resources Corp. has bolted-on acreage in several deals, including a smaller one with Rex Energy Corp. in southeast Ohio.

The EQT and Rice merger was a chain reaction of sorts. In May 2016, Vantage Energy Inc. outbid Rice for a large acreage package near its core in southwest Pennsylvania in a bankruptcy auction for coal producer Alpha Natural Resources Inc.’s natural gas assets. Months later, Vantage was acquired by Rice. Operational philosophies are also coming into play as companies like EQT want room for longer laterals and more efficiency, or as producers turn their attention elsewhere.

Noble Energy Inc. and Anadarko Petroleum Corp. recently exited the basin in $1 billion-plus deals, selling to companies backed by PE firms such as Quantum Energy Partners and the Blackstone Group. Those producers left to focus on oil and liquids production in areas such as the Denver-Julesburg Basin, the deepwater Gulf of Mexico and the Permian Basin, among others.

“You’re going to see companies that have not reached a critical mass in the play exiting,” Krasny said of the Marcellus and Utica shales. “We’re beginning to see the elements of that happening. Noble is a great example. You see private equity coming and kind of swooping in and playing that angle right now.”

Infrastructure Affects Dealmaking

Production in the Northeast has grown tomore than 23 Bcf/dfrom less than 8 Bcf/d five years ago. There are 20 pipeline projects being developed to serve growing volumes, which could reverse production constraints and create a new problem by not having enough gas to fill them, according to RBN Energy LLC.

Kalnin Ventures LLC’s Christopher Kalnin, managing director of the energy investment firm, said the infrastructure build-out is creating a need to drill and a need for capital that’s influencing the mergers and acquisitions (M&A) market throughout the basin. Speakers on Wednesday’s panel agreed that the EQT/Rice tie-up, along with the other deals that have been completed over the last year, may be a precursor of what’s to come.

“This is one of many future consolidations that we’re going to see in the play if you look at the upstream players versus the midstream players; I really do see a lot of fragmentation on the upstream side,” Kalnin said. “I think it’s really inevitable that the upstream consolidates over the next three to five years.”

The midstream sector is forcing producers to redistribute the deck, he said. “We are in a window of time right now where transactions are going to really pick up as a function of companies needing to rethink their strategies and portfolios and their commitments to a lot of these takeaway capacity pipelines.”

Krasny said pipeline projects in the Northeast are also tempering the market. Buyers are “still very cautious” of basis differentials and midstream contracts.

Northeast growth and the recent consolidation has found prospects for smaller producers narrowing. “We sold our Marcellus rights several years ago in the early stages of the play,” said Carbon Natural Gas Company CEO Patrick McDonald. “We came to the conclusion that it was going to become a big boy play and we didn’t have the capital to properly compete.”

Carbon operates mostly conventional oil and gas wells in West Virginia, Kentucky and Tennessee. It’s focused on workovers and recompletions now because “it’s really hard to make the economics work” for a new well, McDonald said.

Consolidation is expected to continue not just in Appalachia, but across the U.S. onshore. For example, money has poured into the Permian Basin, which along with Oklahoma’s stacked reservoirs, should surpass all onshore areas for oil drilling and activity this year.

PwC said in a recent survey that U.S. oil and gas industry M&A activity set a record in 1Q2017 at $73 billion, increasing 160% over the year-ago period. The upstream segment remained “red-hot” during the first quarter, the firm said, with a total of 32 deals worth $36.60 billion. PwC said the market was stoked by President Trump’s pro-energy policy, steady oil prices and advances in shale technology.

Oil has since slumped and natural gas prices have seen little movement. But the price deck has given natural gas buyers and sellers something to coalesce around. Kalnin said the “lower for longer” expectations for natural gas are being built into valuations and providing something for the market to agree on in the Northeast.

Stacked Pay

For the Appalachian Basin’s long-term prospects, McDonald pointed to the past. “There’s a saying from the old timers — I’m not sure if it’s really still true today — they said the Appalachian Basin is the most heavily drilled, but least explored basin in the United States.

“It’s a basin that has stacked hydrocarbons throughout the stratigraphic section. We believe there are deeper plays in the Cambrian and Ordovician that are going to become viable here as time goes on.” He highlighted the Rogersville Shale in West Virginia and Kentucky, where larger independents like EQT and Cabot Oil & Gas Corp. have drilled test wells with varying results.

At $50/bbl oil, and natural gas prices stuck in limbo, the Rogersville is unlikely to take off anytime soon, but conference speakers said it can’t be overlooked in the conversations that shape the future of development across the basin.

“It’s a multi-bench play, there’s no question about that,” Krasny said. “It will take time for the industry to advance delineation to where the markets start recognizing” some of those horizons in valuations.

For now, it’s likely that the larger independents and the PE firms that have come and gone throughout the basin’s cycles are going to shape the next phase of development in the coming years.

“I think it’s true in any play; operational and geographical focus is the key to successful outcomes. It’s essential. When we acquire things that have disparate parts, we do the best we can to hive off those parts until it makes sense for the overall strategy,” McDonald said. “There seems to be a willing buyer for things that one doesn’t want. But at the end of the day, we think the only way to achieve right sizing and honest economies of scale, is to be very, very closely focused.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |