Fracking, Monterey Not Expected to Boom in California, Scientists Say

As a third piece of an ongoing scientific assessment of California’s oil and natural gas sector mandated as part of the new well stimulation rules called for in SB 4, a team of earth scientists is examining the Monterey Shale, but their early observations released on Wednesday indicate they don’t expect their work or the new rules to change much near term in the state’s oil/gas patch.

“There is a lot of speculation about the Monterey’s ability to change the producing profile of the state,” said Jane Long, a scientist with the California Council on Science and Technology (CCST) and the co-leader of the California SB 4 independent assessment, adding that her team’s work will determine how imminent or realistic large reserves might be in the Monterey. “We’ll be looking at the scenario of if it ever does get developed, what kind of impact would that produce.”

Her conclusion for now is that no past or current estimates on the Monterey are very reliable, and the data doesn’t exist now to understand the potential of the Monterey formation. The Long analytical team, which includes scientists from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, also examined possible natural gas formations in the state and concluded that there isn’t anything like the Marcellus looming on the horizon.

The statewide assessment will look at three technologies called out in the state’s well stimulation rules: hydraulic fracturing (fracking), acid fracturing and matrix acidation. “Acid fracturing isn’t used much in California because it only works when you have the kind of rocks that can be dissolved easily by acid, and we don’t have those kinds of rocks in California,” Long said. “Those are found in carbonate reservoirs and we don’t have them.”

Matrix acidation is used, but only about 10% as much as fracking. Thus, Long said the focus of the assessment will mostly zero in on hydraulic fracturing, which in recent years has been associated with about 20% of the oil and gas produced in the state.

About half of the wells drilled each month (300) use fracking, she said. “The reason only 20% of the production involves fracking is because wells hydraulically fractured are not as efficient as other forms of production,” Long said. “We fracture a lot more wells and get less than a proportional amount of oil out of those wells.”

A source with small independent Santa Maria Energy told NGI‘sShale Daily earlier in the month that there is too much emphasis on fracking, and zero emphasis on cyclic steam which has been safely used in Santa Barbara County for the past 60 years by companies such as Santa Maria Energy. There is no fracking taking place in Santa Barbara.

Long and state energy officials maintain that the oil/gas operating practices in California are a lot different than what is done in the high-profile shale plays in the Bakken, Eagle Ford, Utica and Marcellus. “The wells in California tend to be fairly short and vertical; we tend to use a thick gel-like fracking fluid, and the purpose is to open up one short fracture that connects to a series of other fractures, compared to the long-reach horizontal wells with multiple fracking stages in other states.”

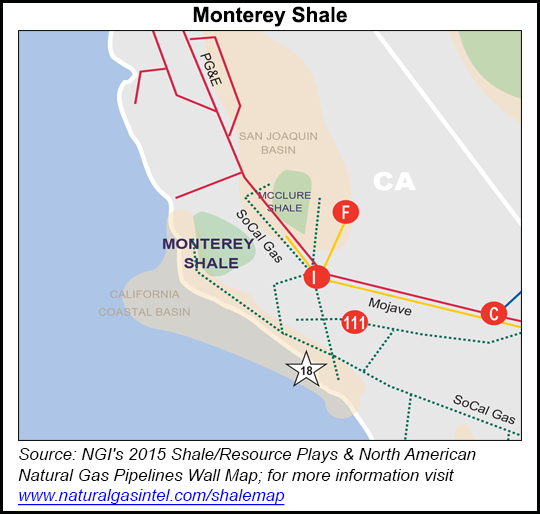

So, since California operators are using fracking in what Long called “a very different way,” the “conclusions people have drawn about hydraulic fracturing are not true in California,” she said, adding that 96% of the fracking in the state is done in the San Joaquin Valley, and 85% of it is done in four fields.

Long expects the future for California oil/gas operations will look a lot like it does today, and the Monterey Shale will continue to be somewhat of an untapped resource. “The Monterey Shale is much more unlikely to be a target going forward,” said Long, citing the change in estimates by the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA).

Last spring, EIA cut its estimate of recoverable oil in Monterey Shale to 600 million bbl, a 96% decrease from previous estimates (see Shale Daily, May 21, 2014). The revision came nearly three years after EIA had estimated Lower 48 technically recoverable shale oil resources at 23.9 billion bbl, including 15.4 billion bbl in the Monterey/Santos play, then believed to be the nation’s largest shale oil formation (see Shale Daily, July 11, 2011).

Long said that unlike the “deep rock” resources that EIA was originally counting, most oil produced in California today comes from “migrating oil supplies” that travel from deeper formations. “The shales in the Monterey are in large part deep, where the oil was formed,” she said. “Basically, we don’t think [Monterey production] is imminent, but we think it is possible.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |