E&P | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Finally Toppled by Debt, Chesapeake in Bankruptcy

Chesapeake Energy Corp., once a symbol of the American natural gas industry’s revival and a disruptive leader that helped spark the nation’s unconventional boom, filed for Chapter 11 protection on Sunday to wipe out $7 billion of debt.

The move follows months of speculation and years of cost-cutting initiatives at the Oklahoma City-based independent, which has at one time or another operated in nearly all of the Lower 48’s major plays. The company started warning last year that persistently low commodity prices and its mountain of debt could lead to insolvency.

“We are fundamentally resetting Chesapeake’s capital structure and business to address our legacy financial weaknesses and capitalize on our substantial operational strengths,” said CEO Doug Lawler.

Chesapeake filed for protection in the U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of Texas. Under a restructuring support agreement reached with creditors, the company has arranged for $925 million of debtor-in-possession financing to support its operations.

The company and some lenders have also agreed to the principal terms of a $2.5 billion financing package for when it exits bankruptcy, consisting of a $1.75 billion revolving credit facility and a $750 million term loan. The company has also gained support from term lenders and secured note holders for a $600 million rights offering upon exiting bankruptcy.

Chesapeake said it would continue to operate normally throughout the restructuring process, primarily aimed at strengthening its balance sheet and realigning legacy contractual obligations.

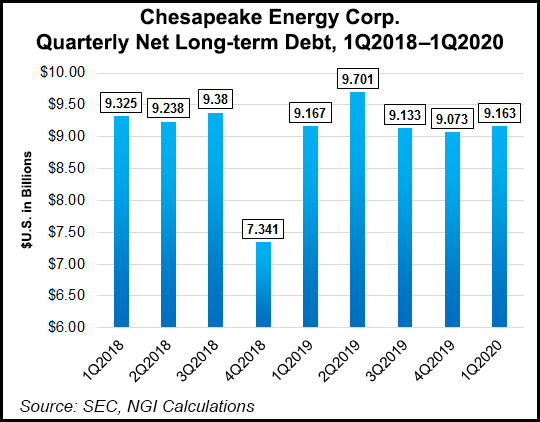

The bankruptcy is representative of the struggles the Lower 48 industry has faced amid the Covid-19 pandemic. Chesapeake has for years struggled with debt and had more than $9 billion on the books at the end of the first quarter. However, the virus outbreak crushed demand and tanked commodity prices, creating more uncertainty for the one-time giant.

Co-founded by the late Aubrey McClendon and Tom Ward, Chesapeake at one time had more than 100 rigs operating across the Lower 48 and was valued at nearly $40 billion.

“It’s difficult to point to another company that made more of a widespread impact on the U.S. shale sector than Chesapeake,” said Wood Mackenzie analyst Alex Beeker. “Chesapeake showed the market — and its competitors — how quickly production could grow, how fast projects could develop, and what the updated U.S. model for engaging with stakeholders looked like. Remember they brought international upstream investors back to the U.S. onshore.”

Still, the portfolio became burdensome and carried billions in expenses that couldn’t be tamed, creating an unsustainable path.

“The massive financial burden of investing first into the shale gas boom, then its failed attempt to grow a similar strong position on oil plays, have brought the giant to its knees,” said Rystad Energy’s head of analysis Per Magnus Nysveen.

The company has more recently focused on whittling its asset base, transforming from a natural gas juggernaut into an oil producer under the leadership of Lawler, who took over in 2013 and focused on cost-cutting. The bankruptcy comes even after $20 billion of leverage and financial commitments were eliminated in recent years.

Chesapeake still has an expansive asset base, with operations in the Eagle Ford, Haynesville and Marcellus shales, along with the Midcontinent and Powder River Basin (PRB). Third parties were already moving quickly on Monday to reassure investors that their operations wouldn’t be impacted by the restructuring.

Crestwood Equity Partners LP, which has midstream assets in the PRB and Marcellus supported by Chesapeake acreage, said it was prepared to continue offering the producer services during the bankruptcy and said it anticipates no changes to this year’s financial forecast.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |