Regulatory | LNG | LNG Insight | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

FERC Approves Three LNG Export Projects, Additional Liquefaction Train in South Texas

FERC on Thursday approved three liquefied natural gas (LNG) export projects proposed for Cameron County, TX, and certificated an additional liquefaction train to be located at Cheniere Energy Inc.’s existing South Texas export facility.

The projects, proposed by Texas LNG Brownsville LLC, Rio Grande LNG LLC and Rio Bravo Pipeline Co., Annova LNG Common Infrastructure LLC, and Cheniere all have applications pending before the U.S. Department of Energy seeking authorization to export gas to countries without free trade agreements with the United States.

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission approved Texas LNG Brownsville LLC’s proposal for a 4 million metric ton/year (mmty) LNG export terminal on the Brownsville Ship Channel in Cameron County, TX. [CP16-116]. The terminal would be fed via a yet-to-be-constructed intrastate pipeline accessing gas supplies from the Agua Dulce hub near Corpus Christi and about 150 miles to the north of Brownsville. The pipeline would potentially serve other LNG export terminals as well as industrial and power generation facilities and export markets in Mexico, according to Texas LNG.

The Agua Dulce hub interconnects with interstate and intrastate pipelines such as Texas Eastern Transmission, Tennessee Gas Pipeline, facilities of Energy Transfer Partners and Enterprise Products Partners, Natural Gas Pipeline Co. of America and Transcontinental Gas Pipe Line.

FERC also approved Rio Grande LNG and the Rio Bravo Pipeline’s proposal for an LNG export terminal to be built on a 1,000-acre industrial site in Cameron County at the Port of Brownsville [CP16-454, CP16-455]. According to FERC documents, the terminal would have 27 mmty of export capacity and six liquefaction trains, each with a nominal capacity of 4.5 mmty. It would also have four LNG tanks each with a capacity of 180,000 cubic meters; LNG truck loading facilities with four loading bays, each with a capacity to load 12-15 trucks per day; and a new marine slip for two LNG vessel berths, with capacities of 125,000-185,000 cubic meters.

The pipeline system would include two 42-inch diameter pipelines running in parallel for 137.5 miles from the Agua Dulce market area near Corpus Christi to Brownsville.

In addition, FERC approved Houston-based Annova’s proposal to construct an LNG export terminal to include six liquefaction trains, each with a nameplate capacity of 1 mmty, for an aggregate nameplate capacity of 6 mmty and a maximum output at optimal operating conditions of 6.95 mmty on the Brownsville Ship Channel [CP16-480]. Annova, a unit of Exelon Corp., has said the project would meet the requirements of multiple foreign purchasers whose annual demand is best met with increments of 1 mmty.

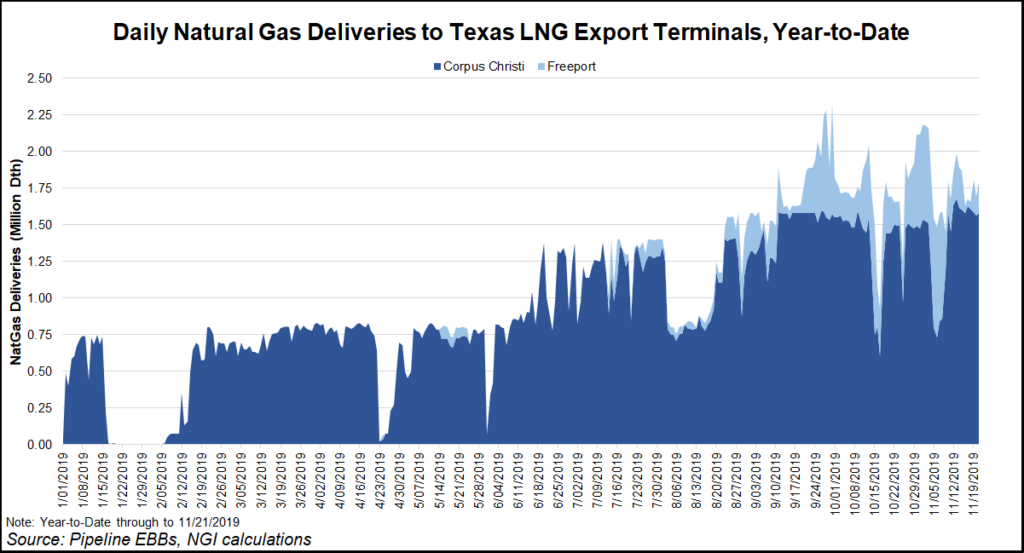

Also approved Thursday was Cheniere’s request to build a third train at the Corpus Christi natural gas export project [CP18-512]. The project would allow Cheniere to liquefy for export an additional 11.45 mmty at the Corpus Christi Liquefaction LNG terminal now operating in San Patricio and Nueces counties in Texas, FERC said.

Approval of the projects “marks a significant addition to the number of LNG export facilities approved by FERC this year,” the agency said.

“Since the beginning of calendar year 2019, the commission has certificated 20.2 Bcf/d of liquefaction capacity, and 2.8 Bcf/d has entered service,” said Chairman Neil Chatterjee. “At this time, there’s 32 Bcf/d of liquefaction capacity that has been authorized, with 13 Bcf/d of that capacity already under construction, commissioning or preparing for development.”

The applications prompted commissioners Richard Glick and Bernard McNamee to renew their long-running debate over FERC’s responsibility to consider each project’s potential effects on greenhouse gas emissions and climate change. The Rio Grande LNG project alone would emit more than 9 million metric tons of CO2 annually, Glick said.

“I still can’t understand why we’re treating climate change different than all other significant environmental impacts associated with projects,” Glick said. “Actually, I can understand it — because everyone in this room knows why, everyone watching on the internet knows why — it’s because it’s climate change. That’s the subject that no one wants to talk about. That’s the third rail of regulatory politics.

“The irony is a commissioner can say, ‘I don’t believe in climate change, that 95% of the world’s scientists are wrong here.’ Everyone has the right to do that, and then you can say, ‘therefore, I’m deciding there’s no significant environmental impacts associated with the greenhouse gas emissions associated with the project.’ But we’re not even doing that. We’re just saying ‘we can’t consider the significance.'”

McNamee, on the other hand, sees FERC’s role as something of a balancing act between regulations that bind FERC, including the Natural Gas Act (NGA) and National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and more recent court decisions.

“My view is as a commission we’re still bound by the text of the NGA and NEPA as enacted by congress, and by the interpretations of those acts by the U.S. Supreme Court as well as the D.C. Circuit, and that our obligation is to read those statutes and the case law in harmony,” McNamee said. “Therefore, my concurrence is an attempt to articulate how we can read all those pieces in harmony, and why the commission continues to follow the requirements within the limitations imposed on us by the acts and the courts on what we can do in relation to measuring greenhouse gas emissions and the conditioning of whether we approve such a facility.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |