NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report | E&P | Markets | NGI All News Access

‘Epic’ Deepwater Oil, Gas Cost Reductions Facing Inflationary Headwinds, Says Wood Mackenzie

The deepwater oil and gas industry has come out of its sustained downturn, but it now faces impending cyclical cost inflation that could wreak havoc on its work to cut expenses, according to Wood Mackenzie.

Since 2013, the cost to develop new deepwater oil and gas barrels has fallen by more than half, as project costs have fallen and returns improved.

“One of the key drivers in cost reduction in deepwater projects is lower rig costs, which is a cyclical factor,” Wood Mackenzie research director Angus Rodger said. “But more importantly, there have also been big structural changes, such as the faster drilling of wells. For example, in the U.S. Gulf of Mexico it now takes half the time to drill a deepwater well compared to 2014.”

Reduced costs have come as some operators downsized projects or focused more on subsea tiebacks and brownfield projects. Project lead times have been reduced, along with well counts.

Larger developments now are phased in, while technology gains have led to faster well completions, better project execution and lower rig and oilfield service sector costs.

According to Wood Mackenzie, the “most competitive” deepwater region is the Americas, and in particular the Gulf of Mexico (GOM), Brazil and Guyana, where more than 50 billion boe of pre- and post-sanction developments may be profitable at an average oil price of $60/bbl, based on break-even costs.

Better project execution also has reduced overspend and improved returns.

“The average deepwater project sanctioned between 2014 and 2016 has started up around 5% under budget, compared to projects from 2006 to 2013, when cost overruns between 10% and 15% were the norm,” researchers said.

Encouraged by the progress and the future need for deepwater oil and gas, the industry has been increasing its investments in the sector.

Total annual deepwater capital expenditure (capex) is expected to reach nearly $60 billion by 2022, up by about $10 billion from today, according to Wood Mackenzie. The increase is to be driven by big projects offshore Brazil, Guyana and Mozambique.

However, the capex increase and additional development likely will accelerate a return to cyclical cost inflation. Total deepwater rig capacity is forecast to decline over the next few years as older, less efficient units are stacked. That means day rates could double by the early 2020s.

“The return of cyclical inflation could see this epic period of deepwater cost reduction come to a close,” Rodger said. “The question now is how much of the ‘structural’ cost savings we have seen through the downturn will prove sustainable through the investment cycle,” and how many are only short-term company adaptations.

“We believe that many cost savings are not as ‘sticky’ as industry suggests, and are skeptical that many will stand the test of time during a sustained cyclical uptick.”

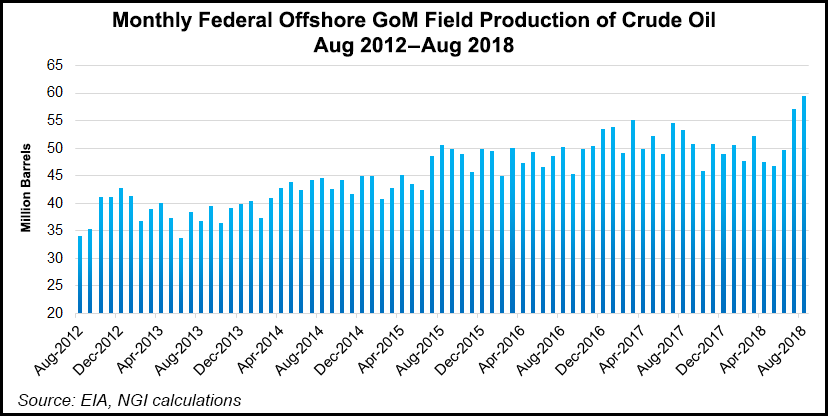

Earlier this month the Big Foot deepwater project offshore Louisiana, led by Chevron Corp., ramped up. It is expected to produce copious oil and natural gas, according to the Energy Information Administration (EIA).

Big Foot, which may hold up to 14 Bcf, is one of 10 gas-rich producing fields ramping up in the GOM this year, EIA said. Eight more gas-heavy fields are scheduled to begin producing in 2019, according to information reported to the Department of Interior’s Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement.

“These new field starts may slow or reverse the long-term decline” in U.S. offshore output, EIA researchers said. “The 16 projects starting in 2018 and 2019 have a combined natural gas resource estimate of about 836 Bcf.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |