NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report | Coronavirus | Markets | NGI All News Access

Coronavirus Wreaks Havoc on Markets; Enverus More Optimistic on Oil Demand

An oil price war launched by the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and Russia battered crude oil and stocks Monday, but the long-term ramifications may not be all doom and gloom for natural gas, especially in the Permian Basin, according to analysts.

West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude plunged as low as $27.34/bbl early Monday but bounced back several dollars before midday. “With WTI prices now in the low $30s, there aren’t too many plays in the Lower 48 that are now economic,” said NGI’s Patrick Rau, director of Strategy & Research.

Enverus analysts also said Monday’s price action would put most crude-focused areas in the Lower 48 out of the economic window for operators to drill, without hedges in place. “Should the market see these prices for an extended period of time, it could ultimately prop up gas prices as associated gas production would likely decline.”

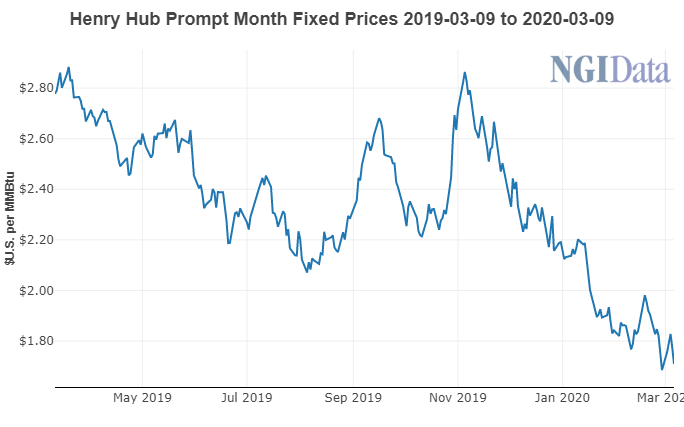

That potential appeared to play out Monday in natural gas futures trading. The April Nymex gas contract, which plunged as much as 9.8 cents from Friday’s close to an intraday low of $1.610/MMBtu, went on to settle in positive territory.

More than any other market, the Permian could see a meaningful rebound in gas prices in the wake of lower crude. Permian gas prices have remained under pressure for the last couple of years as rampant liquids drilling has resulted in increased associated gas production in the region. A lack of gas takeaway, however, has resulted in steep discounts throughout the basin, with gas trading well into negative territory and sinking to record lows last spring.

While there may be some areas of the Permian that may be “slightly in the money, those areas would be the best acreage, and who is going to want to deplete their best inventory in this environment?” Rau asked.

Last week during the annual analyst meeting and before the Russia-OPEC price war, ExxonMobil CEO Darren Woods said the company is pulling back on dry natural gas production in North America and evaluating the pace of near-term development activities in the Permian “in response to market conditions…”

“This could very well lead to a material negative impact on U.S. oil production in the months ahead,” Rau said. However, any significant pullback in crude drilling, especially in the Permian, should help slow U.S. natural gas production. “That may not cause a sudden rush into positive territory for West Texas gas prices, but it should surely help slow the oversupply in that region.”

Goldman Sachs analysts estimated if its covered producers invest on the basis of $30-45 WTI over the next five quarters, “we will see more than 1 Bcf/d (net) less U.S. gas production.”

Meanwhile, for smaller exploration and production (E&P) companies that already were under pressure to consolidate, the deterioration of oil prices accelerates the timeline for integration, according to Rau. The majors and independents with strong balance sheets and a long-term view on oil could be presented with a number of opportunities to pick up assets on the cheap, particularly those drowning in debt.

“This is especially true since unlike the last downturn five years ago, financing by and large is no longer available to the small-to-mid cap names.”

RBN Energy LLC CEO Rusty Braziel acknowledged that these will be hard times for U.S. E&Ps, with the weaker among them facing bankruptcy and the stronger hunkering down to weather the storm. However, “even though we are witnessing unprecedented market conditions, it’s not Armageddon,” Braziel said.

Backing up his rationale, the RBN chief noted that it may take some time for lower prices to have a significant detrimental impact on crude oil production. Also, U.S. producers can get very creative when in survival mode, as they did during the last oil price crash in late 2014. “Though, it’s got to be acknowledged that market conditions this time around do look formidable and many of the E&Ps’ rabbits may already have been pulled out of their hats,” Braziel said.

Furthermore, low prices do not make oil and gas in the ground disappear, Braziel noted. They simply make it less profitable to extract therefore less of it gets extracted. “In effect, low prices motivate owners of that oil and gas (producers holding reserves) to put that production on hold — to ”store it in the rock,’ you might say — and wait to withdraw it until the price is right.”

Braziel said the market likely is facing a similar situation to the collapse nearly six years ago, when low prices cut production for a time, but a subsequent rebound in prices spurred producers to renew drilling programs and improve productivity. “Sadly, it may not be the same E&Ps, since the weaker among them are unlikely to survive the 2020 downturn. But others will. They’ll pick up the assets left behind by the shuttered companies for a song, and be well-positioned for an eventual recovery.”

In the long term, the Lower 48 E&Ps will win the war, Braziel prognosticated. “Because there is just too much oil and gas sitting in U.S. shale plays that is ready and able to be produced in short order when the time, and the price, is right.”

Enverus’ Sarp Oksan, director of Energy Analytics, said even before the coronavirus and oil price crash, operators indicated they were open to further activity reductions if prices deteriorated further. “Now it is a race to the bottom with very different implications for shale this time around than the initial price war of 2014-2016,” Oksan told NGI.

Operators that are not hedged would certainly reconsider their capex plans and revise downward, especially since most plans were set in place with $50-55 crude and $2-plus gas prices in mind, according to Oksan. Should U.S. production declines follow close to natural decline levels, meaning all activity is decimated, 40-60% declines could be expected in the first year, which would turn the market into a supply deficit and help prices rebound, he said.

“Russia and Saudi Arabia both have rainy day funds that mean that at $30 crude, they can meet budgetary obligations” for at least one year. “This means they are unlikely to back down,” Oksan said.

Last week, the coronavirus, officially named Covid-19, was the biggest issue looming over the oil market, but now the market share war has dominated concerns, according to Oksan, with virus demand worries just adding “insult to injury.”

However, some of the spending and activity cuts implemented by producers would be partially offset by efficiency gains and operators choosing to drill in core areas with more of a development plan that could impact productivity to the upside, he said. Some of these areas have transitioned into development mode, however, and there have been parent-child issues in which some areas post deterioration in type curves.

“Should our operators be able to address spacing as more of a science, rather than a science experiment, we should be able to mitigate a lot of the interference issues, space correctly and actually see a bump in production again this year although we have a lower capex spend across the board,” Oksan said.

Meanwhile, real-time measures of global traffic congestion and power consumption, as well as other data, in the wake of the coronavirus were pointing to a less dire scenario for global oil demand this year before the all-out oil price war was launched.

Ahead of the weekend’s developments, Enverus Vice President Al Salazar projected that total world oil demand would grow at a modest 600,000 b/d in 2020, which was considerably higher than some no-growth, or decline, scenarios offered by other analysts.

However, the OPEC price cuts “add a significant wrinkle to the discussion,” Salazar told NGI. “This is truly a unique point in the market’s history, as normally such low oil prices would incent demand. However, Covid-19 has effectively handcuffed such a response from occurring, at least until the virus subsides to a point where the greater populace feels safe.”

The Enverus analyst said based on the number of people on lockdown as of late last week, whether voluntary or involuntary, China is “easily” shedding more than 1 million b/d of oil demand in the first quarter. That estimate is based on a projected loss of 1% in global gross domestic product (GDP) growth this year compared to the firm’s pre-coronavirus case, which also is the midway point between the best- and worst-case scenarios for GDP growth issued by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development earlier this month, ahead of the failed deal to trim output.

“It’s important to note that data on the Chinese economy and oil demand are opaque to begin with,” said Salazar. “At this point, there is no authoritative count for how much Chinese oil consumption is offline.”

The International Energy Agency (IEA) unsurprisingly said Monday demand is expected to decline this year. In its central base case, demand this year is seen declining for the first time since 2009 because of the “deep contraction” in China’s oil demand, as well as major disruptions to global travel and trade.

“The coronavirus crisis is affecting a wide range of energy markets — including coal, gas and renewables — but its impact on oil markets is particularly severe because it is stopping people and goods from moving around, dealing a heavy blow to demand for transport fuels,” said IEA Executive Director Fatih Birol.

However, during a webinar last week exploring the impact of the coronavirus on global oil demand, Salazar noted that IEA data often is revised several months later and other data sets don’t reflect the full picture. “Some analysts point to drastically reduced Chinese refinery runs, reduced Chinese imports and other one-off measures, but the problem is none of these equate to actual consumption,” he said.

Although Salazar said that the outbreak situation remains “very fluid,” there are some real-time indicators that paint a more holistic view for projecting oil demand. One of these is the Chinese Purchasing Managers Index (PMI), which provides an early indication each month of economic activities in the Chinese manufacturing sector.

The PMI plunged to 35.7 in February 2020, down from 50 in January and the lowest level since the survey began in April 2004, “which is a clear, loud warning about Chinese manufacturing sentiment deteriorating,” according to Salazar.

The TomTom Traffic Index, a real-time measure of global traffic congestion, showed that for Wuhan, the epicenter of the virus in China, traffic was 40% less congested than the same time last year. However, for other areas under some form of lockdown, there has been increased congestion since mid-February and in some cities, traffic congestion is back to normal.

“In the past two weeks, we’ve seen a 10-20% improvement/increase in traffic congestion,” Salazar said. “Overall, this data suggests that Chinese gasoline consumption in March should be higher than last month and could be back to normal in the second quarter.”

Other factors also point to an improvement in Chinese economies. Power consumption data remains roughly 30% lower year/year, but is slowly improving, according to Enverus. Salazar noted that less mobility in China due to the coronavirus has had the unintended consequence of improved air quality, which has been confirmed in satellite images from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

Salazar said he doesn’t believe the market is pricing in some of the more positive trends being reflected in the TomTom and power consumption data. “That, to me, is almost a counter-consensus viewpoint…that things could be back to normal in the second quarter.”

He also noted that the Chinese government has pledged to meet this year’s economic targets as well as China’s obligations under phase one of the U.S.-China trade deal. “Despite the shocks on the economy, a significant catch-up is needed to achieve this,” Salazar said. “China has a history of persevering under difficult economic conditions.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |