NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report | Coronavirus | LNG | LNG Insight | Markets | NGI All News Access

Coronavirus Threat Scrambling Markets to Gauge Oil, NatGas Demand Destruction

Global energy markets are struggling to gauge the potential impacts of the coronavirus, which has continued to spread rapidly, raising the specter of what could be a major demand disruption at a time when worldwide oil and natural gas supplies are abundant.

China, the world’s second largest economy, which according to the World Bank accounted for 15.8% of global gross domestic product in 2018, has been increasingly isolated as other countries scramble to contain the outbreak. Travel and other restrictions in China and across the world are posing major economic risks that are also weighing on financial markets.

While the mortality rate is far lower than the 2003 SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) outbreak, the coronavirus has already impacted more people at a time when China’s economy is far larger than it once was. China is the second largest crude importer in the world and is the second largest liquefied natural gas (LNG) importer.

Brent crude, the global oil benchmark, has plummeted since mid-January when reported cases more than tripled, falling from $64.05/bbl at that time to $53.96 on Tuesday, its lowest point since 2018. West Texas Intermediate (WTI) prices settled below $50.00/bbl for the first time in a year on Tuesday, settling at $49.61/bbl. Early last month, the U.S. benchmark topped $65.00/bbl.

The Japan Korea Marker (JKM), a benchmark for LNG in Northeast Asia, is in uncharted territory, with the spot month settling at $3.700/MMBtu on Tuesday on oversupply and fears over how the virus may impact demand.

While China is an important end-market for LNG, it grew slower in 2019 than it did in the two previous years given trade tensions with the United States and slower coal-to-gas switching, among other things. However, the market impact remains difficult to determine how much the coronavirus could take out of the global gas trade.

In 2003, Chinese LNG imports were essentially nonexistent. Last year, the country imported 73.5 billion cubic meters (2.6 Tcf), according to BP plc’s annual Statistical Review of World Energy.

“It is hard to quantify but given the size of China’s consumption now relative to 17 years ago, the impact could be an order of magnitude greater on the broader LNG market than SARS had on analogous markets,” including liquefied petroleum gas, said Evercore ISI analyst Sean Morgan.

“The biggest question is how long any related economic slowdown in China will be due to this nascent outbreak,” he told NGI. “If it is contained quickly we might be able to weather this relatively well.”

Despite a phase one trade deal between the United States and China that was signed to ease tensions last month, “there is still no indication of Chinese buying of U.S. cargoes,” said Energy Aspects’ James Waddell, senior global gas analyst in London.

“The impact of the coronavirus is therefore unlikely to dent Chinese buying of U.S. cargoes specifically,” he said Monday. “But the likely slowdown in demand will further detract from the already depressed demand in” North Asia, which has been “offering unprofitable netbacks to U.S. export facilities since the middle of last month.”

The globe is awash in LNG. The JKM spot month is actually higher than European benchmarks, which finished at about $3.00/MMBtu on Tuesday. Prices in Northeast Asia, which have in recent years been above $10 or higher, are practically unthinkable.

Waddell said cargo tracking indicates that Chinese LNG imports are currently poised to fall compared to data for the same time last year. Reports surfaced on Monday of at least one vessel turning away from mainland China. According to ClipperData, however, a number of ships carrying more LNG is still on their way to the country.

“A slowdown in demand downstream of terminals after an already mild winter will test the storage capacity” at Chinese import terminals, Waddell added.

It’s likely that Chinese buyers will first try to defer other cargoes that haven’t yet shipped or are still far away, said ClipperData’s Kaleem Asghar, director of LNG analytics. If that fails, he said, buyers could try reselling them — a tough prospect in an oversupplied market. It’s also unclear if China’s major state-owned importers would declare force majeure if they can’t fulfill their contractual obligations.

Complicating the outlook for energy markets is China’s Lunar New Year, which in more than a dozen cities and provinces, including Beijing, has been extended. While manufacturers have long bemoaned a slowdown during the holiday, the coronavirus and shuttered businesses have blurred things even more. Hyundai halted manufacturing operations in South Korea on Tuesday because of problems in its supply chain related to the outbreak. The Lunar New Year is also an active period for travel and consumers.

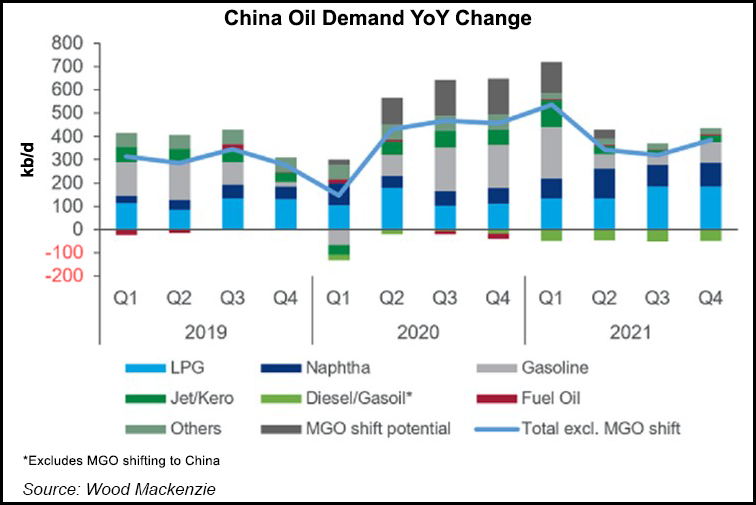

“With respect to the impact on oil demand, as preventive measures focus mainly on aviation and public passenger transport, jet fuel will be the most susceptible,” said Wood Mackenzie consultant Yujiao Lei. “The experience during the 2003 SARS outbreak suggests a severe and one-off impact on China’s demand for jet fuel and, to a lesser degree, gasoline and diesel.”

Analysts at Raymond James & Associates Inc. noted last week that global oil demand slowed for one quarter in 2003 during the SARS outbreak. That virus originated in China and ultimately spread to five continents, but it was declared contained within about three months. China appears to be headed toward a more time-consuming approach of mitigating the coronavirus. What’s more, China’s economy was growing more quickly in 2003 and its oil demand was growing faster too.

Given the differences between then and now, demand destruction estimates for oil have varied widely, ranging anywhere from 200,000 b/d to 3 million b/d over first quarter or full-year time periods.

BP CEO Bob Dudley said Tuesday during a quarterly conference call “there is no question coronavirus, I suspect, will impact demand this year. We’re currently seeing for the year, something around 300,000-500,000 b/d impact on demand growth than we were looking at…coming into this year. Of course, that will unfold as the year progresses. It may be more or less than that, but that is our current estimation.”

China imported 9.3 million b/d of crude oil last year, according to BP’s annual review, most of which came from the Middle East. In a sign of growing fears about demand, the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries was scheduled to meet Tuesday and Wednesday to discuss cutting output, with a possible decision expected sometime next week.

In the United States, given the decline in WTI prices, oil-directed drilling activity could fall in the Lower 48 and impact associated gas volumes. Genscape Inc. senior natural gas analyst Rick Margolin said Tuesday the firm’s “expectations for 2020 gas production growth have been curtailed by nearly 1.4 Bcf/d versus our previous main forecast update from six weeks ago.”

He said “2021 production expectations were reduced by more than 2.3 Bcf/d versus the previous forecast. As a result, 2021 production is now expected to post a year/year decline.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |