NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report | Infrastructure | NGI All News Access

Combined-Cycle Plants Dominate Mexico’s 2019-2033 Power Sector Plan

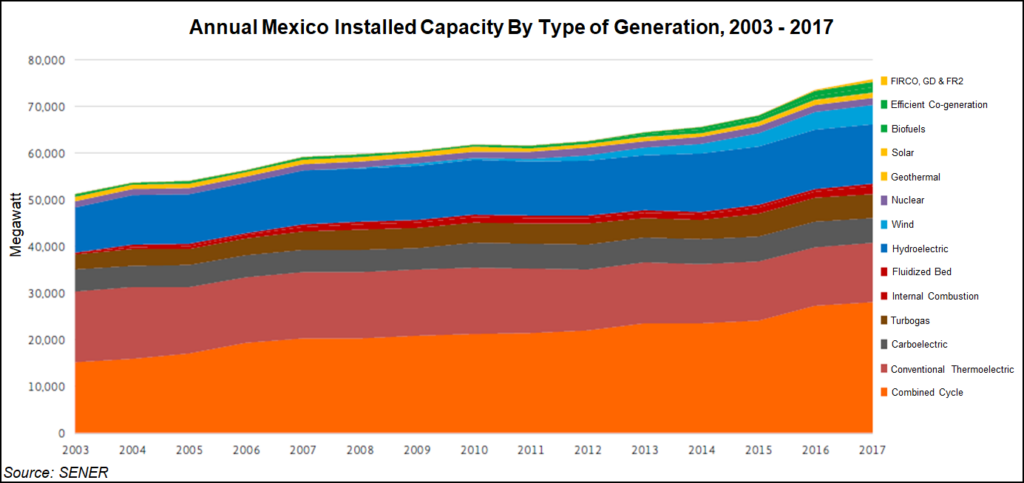

Mexico expects to add an estimated 29,294 MW of combined-cycle gas-fired power generation capacity over the next 15 years, according to the 2019-2033 Prodesen power sector development plan published in late May by energy ministry Sener.

The projected capacity additions compare to a forecast of 28,105 MW for the 2018-2032 period outlined in last year’s Prodesen plan under the previous government. Sener is required to update the document every year.

The latest combined-cycle figure accounts for 41.6% of the 70,313 MW of total capacity seen coming online from 2019-2033, trailed by photovoltaic solar (29.4%), wind (18.9%), hydroelectricity (4.2%) and cogeneration (3.4%).

Amid surging production of inexpensive gas in the United States, Mexico has undertaken a massive buildout of gas pipelines since 2012, and has sought to switch from fuel oil to gas in the power sector. Imports accounted for 67% of Mexico’s gas supply in February, according to Sener.

While last year’s Prodesen report extolled the benefits of attracting private sector investment via long- and medium-term electricity auctions with state-owned utility Comisión Federal de Electricidad (CFE) as the offtaker, this year’s report argued that CFE must be the protagonist of the generation segment.

A list of the document’s guiding principles and priorities leads with “national energy sovereignty, security, and sustainability,” and mandates the application to CFE of “all the regulations that apply to private producers, to ensure competition, equity and equality of conditions.”

“I think that you can start to see what is implied by ”equity,’” Infraestructura Energética Nova (IEnova) CEO Tania Ortiz said last week at the Gulf Coast Power Association’s Mexico Electric Power Market Conference in Mexico City. “There is worry in the new administration that CFE is breaking up and losing efficiency.”

CFE general director Manuel Bartlett has repeatedly expressed opposition to the idea of CFE purchasing electricity via the auctions, arguing that it should instead produce power.

At Sener’s instruction, independent system operator Centro Nacional de Control de Energía (Cenace) has suspended long- and medium-term electricity auctions indefinitely. Freezing the long-term auctions was seen as a blow to the renewable energy segment.

Expansion of Mexico’s power generation fleet, therefore, “most likely will come from natural gas-fueled plants, and those are going to be developed by CFE entirely,” GMEC energy consultancy founder Gonzalo Monroy told NGI’s Mexico GPI. “They’re going to bid out turnkey projects, and the operator will be CFE.”

CFE has 6,234 MW of projects in either the construction or in the testing phase that are scheduled to enter operation from now through 2020, according to the Prodesen report. Of these, 2019 projects include Empalme I (770 MW), Empalme II (791 MW), Topolobampo II (887 MW), Escobedo (857 MW) and Valle de Mexico II (615 MW). The 2020 projects include Topolobampo III (765 MW), Norte III (907 MW) and Centro (642 MW).

Another five proposed CFE combined-cycle projects totaling 3,822 MW of capacity, some of which have entered the tendering phase, are slated to enter operation between 2022 and 2023. They include Salamanca (757 MW), San Luis Potosí (740 MW), San Luís Río Colorado (450 MW), Lerdo (911 MW) and Tuxpan (964 MW).

Monroy warned, however, that transmission bottlenecks and uncertainty over gas infrastructure projects such as the Cempoala compressor station reconfiguration could hinder CFE’s expansion plans and lead to an increase in blackouts, particularly on the Yucatan Peninsula, which relies almost entirely on gas-fired power generation.

“Right now…the peninsula, especially for the following year and a half, is completely exposed,” Monroy said. “There is no backup plan to increase more transmission lines, there is not enough natural gas to supply the existing plants, and there is also no clear path to development of other alternatives [such as] solar power.”

Another major difference between this year’s and last year’s reports relates to the decommissioning of power generation infrastructure. Last year’s report projected the retirement of nearly 12,000 MW of aging capacity, including 7,426 MW conventional thermal, 1,656 MW combined-cycle, 1,400 MW coal, and 1,174 MW of turbo-gas plants.

The 2019-2033 Prodesen report, meanwhile, stated, “In the present planning exercise, in conformity with the new energy policy of the federal public administration,” it did not “consider the retirement of power plants.”

Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador and Bartlett have accused the previous government of seeking to prematurely close CFE’s power plants instead of investing in the plants’ maintenance and modernization.

“Not one more plant will be closed,” the president said last December. “The policy of closing the CFE’s power plants is over.”

By keeping CFE’s most inefficient plants in operation, CFE will almost certainly see a rise in the marginal cost of producing electricity, Monroy said, making it more difficult to fulfill the president’s pledge of lowering electricity prices for end-users.

CFE, Monroy said, is “in a really tight spot.”

The Prodesen report follows the publishing by Mexico’s Centro Nacional de Control del Gas Natural (Cenagas), operator of the Sistrangas national pipeline grid, of the Consulta Pública, a non-binding survey of natural gas market participants to gauge future demand for the fuel.

Respondents from the power sector said that their combined natural gas demand could increase more than six-fold from 2019-2024.

CFE produced 54.2% of Mexico’s electricity in 2018, with the private sector supplying the remainder, according to this year’s Prodesen report.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |