NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report | Markets | NGI All News Access

COLUMN: To Improve Natural Gas Balance in Mexico During Trying Times, Open Capacity

Editor’s Note: NGI’s Mexico Gas Price Index, a leader tracking Mexico natural gas market reform, is offering the following column as part of a regular series on understanding this process, written by Eduardo Prud’homme.

Prud’homme was central to the development of Cenagas, the nation’s natural gas pipeline operator, an entity formed in 2015 as part of the energy reform process. He began his career at national oil company Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex), worked for 14 years at the Energy Regulatory Commission (CRE), rising to be chief economist, and from July 2015 through February served as the ISO chief officer for Cenagas, where he oversaw the technical, commercial and economic management of the nascent Natural Gas Integrated System (Sistrangas).

The opinions and positions expressed by Prud’homme do not necessarily reflect the views of NGI’s Mexico Gas Price Index.

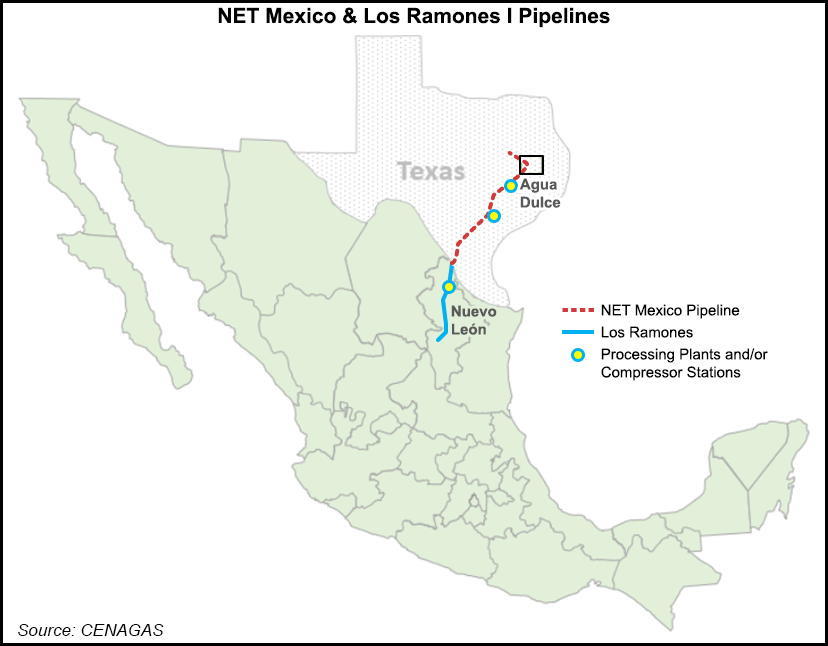

Since its start of operations, the 2.3 Bcf/d Net Mexico pipeline has had enormous weight in the overall gas balance of Mexico. This pipeline, originally sponsored by the international arm of Pemex Gas y Petroquímica Básica (PGPB), is the first segment of the Ramones project.

At 634 miles, it was the largest gas infrastructure developed since the 48-inch trunk pipeline of the National Gas Pipeline System (SNG) was built in the 1970s. The business model was conceived at the end of President Felipe Calderón’s administration as the solution to the regional supply-demand imbalance of natural gas, or critical alerts, observed in various areas of the SNG.

From its original conception, the recovery of its cost was foreseen through a roll-in tariff typical in the then Integrated National Transportation System (STNI), forerunner of the current Sistrangas system. This meant that, although PGPB did not participate directly in the investment in new infrastructure, its commercial control of the transport capacity in the SNG ensured the financial viability of the project through a long-term capacity contract.

The urgency to resolve bottlenecks in the center of the country and the search for redundancy transcended regulatory discussions regarding allocation of costs. However, with the start of the Peña Nieto government, the Ramones project was fragmented into two phases. The second phase in turn was divided into Phase II North and Phase II South. The entries into operation of each of them were scheduled for December 2014 and December 2015, respectively.

In a scenario in which the volume transported in 2012 in the STNI was 4.8 Bcf/d, the promise of increasing the flow rate above 7 Bcf/d in 2016 seemed to be a panacea to all the country’s gas supply problems. But reality always has the last word.

Many events coincided with the start of the Net Mexico pipeline, Gasoductos del Noreste, TAG Pipeline Norte and TAG Pipeline Sur, the systems that ultimately formed the whole project.

First, a structural change occurred with the 2013-2014 reform, which led to the birth of Cenagas, an independent operator that would not only manage Pemex’s pipelines but the capacity contracted by Pemex in private pipelines. Suddenly, Cenagas became the shipper of the pipelines contracted by Pemex in Mexico. And although the new hydrocarbons law endowed Cenagas with powers to manage the capacity of cross-border pipelines such as NET Mexico, the feverish momentum of legislators was limited by the fact that it is only effective up to the border. North of the Rio Grande, contracts in Texas are generally respected beyond government changes, so Pemex simply continued to be the original owner of the capacity.

The second event consisted of the gradual start of operations of Ramones Phase II and the gradual management of the operating balance of Sistrangas and the commercial management of systemic capacity by Cenagas. The operational coordination between these actors and the reconfiguration of financial commitments helped consolidate the vertical disintegration at Pemex that facilitated open access, not only in these pipelines but throughout the integrated system. Financial viability no longer depends on the dominant nature of Pemex’s commercial activity, but rather on Cenagas achieving a robust mass of users who want to transport gas throughout the entire network.

The third occurence is perhaps the least helpful for building a market: Gas balance was badly hit by falling natural gas production by Pemex. The hot summer months of 2016 saw a race against time in which at the same time that the flow injected from Net Mexico increased, the volume that the processing centers in the southeast sent out dropped. The largest increase in infrastructure in history coincided with the most dramatic drop in domestic production.

Day after day, the interconnection between Net Mexico and Gasoductos del Noreste in Río Grande became the main injection point in the entire Mexican gas system. The most important strategic point for Mexican energy security is not the Cactus and Nuevo Pemex processing points, but rather the Agua Dulce Hub in Texas. The gas consumed in the main consumption centers of the country, Monterrey, the Valley of Mexico, Querétaro, Bajío and Puebla come from one of the nine pipelines that flow into the Agua Dulce header. This fact means that the system is hurt every time a scheduled maintenance occurs on Net Mexico.

In 2019, a flow reduction of around 800 MMcf/d for almost a week left the country with a deficit of around 5 Bcf. Similar situations occurred in 2017 and 2018. The way to maintain the balance in the past was through a strategy composed of various measures including the continuous filling and emptying of the Altamira and Manzanillo LNG terminals with the intermediation of CFE and an energy policy that gave priority to gas consumption in conditions of scarcity to the private sector over the electricity sector controlled by CFE.

The Sur de Texas-Tuxpan marine pipeline now helps out in the Sistrangas. The Montegrande interconnection allows the addition of 0.5 Bcf/d to the 48-inch Gulf trunk near Tuxpan. In the injection via Naranjos, the gas that flows through Transportadora de Gas de la Huasteca can replace in Tamazunchale the gas that was previously supplied from the injection in Ramones and can inject between 400 and 500 MMcf/d in the Sistrangas in Pedro Escobedo, near Querétaro.

But effectiveness depends on the consent of CFE so that the capacities contracted throughout the gas network are used, and their willingness to maintain the policy of sacrificing their consumption of gas for the sake of transferring it to the rest of the users. In past columns, I have already pointed out the predominant role that CFE plays in the gas sector. In critical situations such as the one ahead, the differences that exist between CFE and Cenagas can be clearly seen.

While conducting a commercial approach with significant operational and financial leeway in its transactions, the actor responsible by law for achieving continuity and reliability of supply – Cenagas – lacks binding contractual or regulatory instruments that allow it to implement extraordinary measures. Thus, achieving open access that is not unduly discriminatory becomes evident. In a world with multiple shippers, without hoarding and with continuity of routes in transit in different networks, the risk of shortages is mitigated through diversification. The timely information of a scheduled maintenance gives time and space for marketers and users to make forecasts and carry out transactions that allow them to transcend the crisis.

Regardless of the public supply coordination policy assumed by the Energy Ministry, in a strict sense, Cenagas has few means of its own to overcome the capacity restrictions of the Net Mexico Pipeline. According to what Cenagas announced in different forums, the reconfiguration of the Cempoala station should already be in a position to modulate its use and improve the distribution of gas that comes from Texas or from the Tamaulipas and Veracruz fields to the central and southeast.

There is no way to significantly increase imports via Argüelles or Reynosa, although the Libramiento Reynosa project is in the works. Kinder Morgan Monterrey cannot alleviate the reduction on the same scale as what the Ramones and Nueva Era system loses; it is not interconnected with Sistrangas and if it were, the continuity of routes also requires the consent of CFE given its capacity ownership.

In the first two months of 2020, consumption in the Sistrangas has been below that observed in 2019 by approximately 300 Mcf/d. Consumption in the first two months of 2019, in turn, was less than that of 2018 by around 150 MMcf/d. Trying to quantify what will be the drop in gas demand in April given the impacts of the coronavirus is impossible. Most likely, further economic drowsiness will occur leading to lower consumption, but energy efficiency will also decrease in homes. In this context, the annual April maintenance of the Net Mexico pipeline may well occur without problems. The coronavirus will help alleviate the risk of critical alerts, unless of course Pemex’s production continues the rapid downward trend that led it to cease being the country’s main source of supply.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |