NGI All News Access | Infrastructure | LNG Insight

COLUMN: The Promise and Peril of a Changing LNG Market

NGI has for nearly 40 years now covered the evolution of North American natural gas. From deregulation and the rise of a highly competitive market, to the collapse of Enron Corp. and the dawn of unconventional development, the organization has adapted and pressed ahead to what’s next.

While the oil and gas industry faces unprecedented challenges, not the least of which include mounting pressure to better address its climate impacts and disaffected investors, it also has opportunities. In recent years, it’s become increasingly clear that one of the next growth horizons for North American natural gas lies in the export market.

This is why we’ve launched NGI’s LNG Insight: to provide more news, data and context on the rapidly evolving global gas market, and particularly, North America’s role in it. The LNG market of today is far different than the one of the past. For a variety of reasons, the way the super-chilled fuel is bought and sold globally also differs from the way natural gas is traded in much of North America.

Today, there are six export facilities operating in the United States and more under development across the country, as well as in Canada and Mexico. Operational facilities on the Gulf Coast and in Maryland were specifically built or repurposed to export cheap unconventional natural gas.

But liquefaction projects also have long been built to monetize stranded gas, which was historically marketed to buyers that otherwise had little or no access to the commodity, like those in Asia. Such projects were financed by long-term, take-or-pay contracts that were linked to oil and typically included diversion clauses that restricted delivery from one point to another and discouraged the retrade of cargoes that’s becoming dominant in today’s market.

With the 21st century, the European and U.S. markets have been integrated into the LNG world. The abundance of spot trading and healthy futures markets they brought with them first attracted merchants, then investment banks and ultimately major commodity traders such as Gunvor Group Ltd., Trafigura Group Pte. Ltd. and Vitol Inc. The trading houses have had an outsized influence in transforming the global market from one that was built on a rigid model into a more dynamic one that’s becoming increasingly liquid.

The advent of U.S. LNG producers also has led to more spot trading and accelerated a trend that had been gaining momentum. U.S. facilities are underpinned by long-term contracts that are far more flexible. Essentially, they give buyers the option to do what they want with their volumes. For example, a long-term buyer might have sold the right to lift a cargo to somebody else two or three times before it ever gets lifted.

As the market has expanded and become more liberal, it’s created more exposure for benchmarks in Asia, Europe and the United States. While most of the world’s contracts are still linked to crude prices, cargoes are also sold based on U.S. and European gas pipeline benchmarks. But perhaps more tellingly, the Japan Korea Marker (JKM), a pure LNG price, is gaining ground.

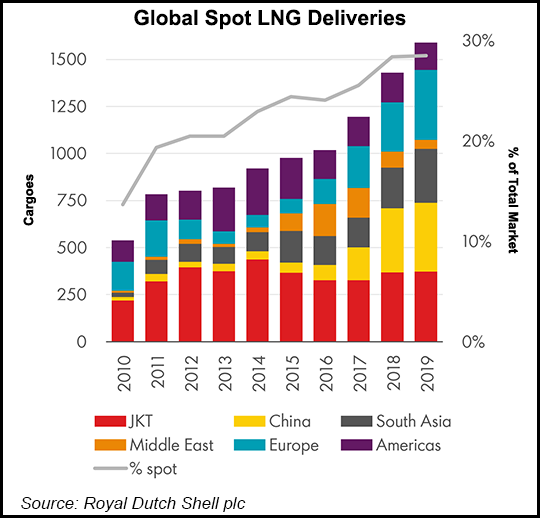

According to Royal Dutch Shell plc, the world’s largest LNG trader, 600,000 lots were traded using the JKM futures contract in 2019, compared with less than 200,000 lots in the prior year. In its fourth annual LNG outlook, Shell in February said spot trading accounted for 30% of all deliveries in 2019, another indication of a rapidly evolving market.

A debate continues over which of the benchmarks in Asia, Europe and the United States best represents the global value of LNG. Will new points emerge and make the current benchmarks irrelevant? Should more effective indexes be developed? Such questions have spurred efforts to find better financial tools for hedging risk and bring more transparency to the marketplace.

The coronavirus has only complicated matters. The outbreak has spread across the globe and tested an LNG market that already faced softening demand. Price volatility has also accelerated since last year, further demonstrating the necessity of more transparency.

“I sort of joke over here that no matter who you are in the market these days, it’s moved against you, it’s moved in the wrong direction…at least once,” said Poten & Partner’s Jason Feer, global head of business intelligence, during a webinar last week. “I think what this highlights is the difficulty the market is facing relying on benchmarks that aren’t really LNG benchmarks. You have so many moving pieces and managing this kind of risk is very difficult, very expensive.”

In the last week alone, Asian spot prices fell to record lows, as did the prompt month for the Dutch Title Transfer Facility, with both dropping below $2.50/MMBtu. Meanwhile, U.S. benchmark Henry Hub has remained in the basement at around $1.60 as all three points seem to converge.

The extraordinary slide in oil prices has narrowed the spread between spot prices and long-term prices linked to oil, which still account for the bulk of global contracts. Suppliers once protected from the weak spot market by oil-linked term prices are now exposed as they’ve fallen well below $5. So a buyer’s market persists, yet for many, the virus appears to be limiting the ability to absorb incremental volumes as economic activity remains in decline in most parts of the world.

Efforts to enhance price discovery and risk management are to be expected in a market that’s still very much being formed, but the pandemic has created another sense of uncertainty in the global gas trade, exacerbating the tectonic shifts that were underway. Headwinds are only expected to intensify, which could imperil even more projects, alter the terms of contracts to better insulate parties from the turmoil of the current market or even change project financing depending on how creditors react.

Going forward, we will be dedicated to explaining these changing dynamics, various elements that have always impacted the global LNG trade and sharing more of what NGI editors learn about the sector in this column.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 |