Regulatory | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Column: New Electricity Rules in Mexico Might Have Far-Reaching Consequences Across Energy Sector

Editor’s Note: NGI’s Mexico Gas Price Index, a leader tracking Mexico natural gas market reform, is offering the following column as part of a regular series on understanding this process, written by Eduardo Prud’homme.

Prud’homme was central to the development of Cenagas, the nation’s natural gas pipeline operator, an entity formed in 2015 as part of the energy reform process. He began his career at national oil company Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex), worked for 14 years at the Energy Regulatory Commission (CRE), rising to be chief economist, and from July 2015 through February served as the ISO chief officer for Cenagas, where he oversaw the technical, commercial and economic management of the nascent Natural Gas Integrated System (Sistrangas). Based in Mexico City, he is the head of Mexico energy consultancy Gadex.

The opinions and positions expressed by Prud’homme do not necessarily reflect the views of NGI’s Mexico Gas Price Index.

The ideological root of Obradorismo, or the philosophy of Mexican president Andrés Manuel López Obrador, comes from the political currents of the Mexican Revolution that shaped the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), which monopolized power for most of the 20th century. One of the symbolic events of this was the oil expropriation carried out in 1938 by president Lázaro Cárdenas, whose bust looms over the courtyard of Pemex headquarters.

Since then, Pemex and sovereignty have been slapped together in political speeches, government programs and in public policy; in the three energy reforms that occurred between 1995 and 2013, it was always unthinkable to put the privatization of Pemex up for discussion. In the 1960s, the electricity industry was nationalized through pressure from trade unions, and power firm CFE joined the list of state companies whose role included helping out society. Both Pemex and CFE, given their economic muscle and geographic omnipresence, have since served as instruments of political and electoral control. They belong to all Mexicans and therefore are manifestations of the nation’s sovereignty, or so the story goes.

Today, energy sovereignty is one of the central pillars of government policy. The neoliberal, free market in its volatility creates winners and losers and is the natural enemy of sovereignty, violating the control that the state has over the energy sector. Moreover, the idea goes, the market has been the breeding ground for corruption and has allowed economic power to hijack political power.

Obradorismo seeks to bring order to the sector. Using this as a framework, the government recently took what may be its most controversial, economically costly and politically risky public policy decision regarding energy. If remediation measures are not taken, long-term private investment in the sector could well stop flowing into the country for what remains of this government’s cycle that ends in 2024.

At the end of April, grid operator Cenace published a decree to guarantee “the efficiency, quality, reliability, continuity and security” of the power sector given demand fluctuations due to the coronavirus lockdown. To start with, the process to convert the decree into public policy was seen as highly dubious. Being a general measure, it would have had to have been evaluated by the Conamer commission tasked with such work. Notwithstanding, the Energy Ministry (Sener) skipped this step. The Conamer director, who had been undersecretary of electricity in Sener during the Peña Nieto government and was responsible for starting the wholesale electricity market (MEM), subsequently resigned the day the decree was published in the Official Gazette, May 15.

The policy basically gives the state the power to select generation options based on the condition of ”reliability,’ overriding market rules. As such, the Cenace decree is seen among companies that participate in the electricity sector as hostile to investment in generation plants, in particular renewable energy. It is the latest assault against green projects by a government that has criticized the presence of wind turbines in various locations in the country for causing visual pollution. The barriers imposed on renewable power contrast with the enthusiasm and massive allocation of financial resources to the construction of a new refinery in Dos Bocas, in Tabasco, the president’s home state.

The media attention has focused on the government’s scant commitment to the energy transition, but the less conspicuous but more important aspects of the scandal lie in the decrease in the technical independence of Cenace, and the alteration of the objectives of the Energy Regulatory Commission (CRE) which include regulating against monopolistic practices.

With the principle of giving precedence to reliability over any other criterion, the market loses its ability to give adequate economic signals to actors in the electricity sector. The distortion of attributions is clear when Sener instructs CFE to participate proactively in the planning of the national electricity system and in determining the guidelines and criteria of ”reliability,’ overriding both Cenace and CRE. Renewable power companies will now take their grievances to the courts, with the rightful argument that the law is on their side.

The distortion of economic incentive in the MEM has a very significant impact on the Mexican gas market too. Simply, the economic conditions favoring natural gas along with the improvement in gas pipeline infrastructure will not serve as the spur to investment under this new environment. Natural gas power will require investment promotion that focuses on independent power producer (IPP) schemes, in which the sale of electricity to CFE is the necessary guarantee to encourage a private investor to venture into a risky market.

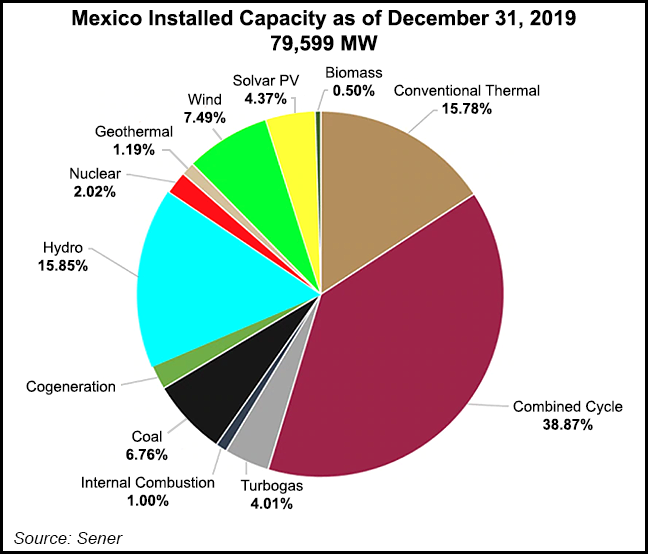

In fact, the precarious conditions of reliability are explained precisely by the delays in the investment programs for combined cycle and turbogas plants that CFE programmed for the 2014-2019 period, which were considered in Cenace planning scenarios and that simply did not occur due to a lack of public resources. And with the fiscal condition as it is in 2020, public investment will be slow, at best.

The Cenace agreement is bad news for the renewables sector, but it is also bad for the gas sector. And the real truth is that Sener’s strategic vision is actually about fuel oil, the fuel oil that has built up in Mexico recently, and is better, according to this vision, than natural gas imported from Texas because of Sener’s aforementioned ”energy sovereignty’ philosophy.

Fuel oil has for decades been the symptom of a national refining system that can’t properly process Mexican heavy crude. Today, the six refineries in the country churn out 125,000 b/d of low quality bunker fuel. The sluggishness of the global economy and the consequent conditions in the market for crude oil and its derivatives puts Mexico in a difficult logistical situation. There is no place to send the fuel oil and there is no place to store it. One option is to further lower crude oil processing in refineries, but that would collapse upstream operations.

Fuel swaps have occurred in this and in past administrations. The lack of natural gas in previous decades led to the use of fuel oil. In the present case, it is the abundance of an undesirable oil, and not the problems of natural gas availability or electrical reliability that underlies the motivation of Sener’s policy, even as the responsiveness and thermal efficiency of gas-based generation is clearly preferable to Cenace engineers.

Mexico’s energy matrix suffers from a serious problem of balance, but this is not due to the stability of the electricity grid, but instead the logistics and refining restrictions seen in the hydrocarbon sector. The pandemic has provided new justification for the implementation of actions aligned to the recovery of ”energy sovereignty.’

President López Obrador himself has suggested that Mexico should stop exporting oil and dedicate its production to satisfy internal energy demand. The construction of the Dos Bocas refinery is a key part of his strategy of displacing gas and oil imports. Economic efficiency has been thrown out the window.

The government will assume the political cost of limiting the penetration of renewables, but without financial resources for the state to become the sole energy provider again, the bet will end in a failure and then we will see real instability in the sector. It will be then that the stubborn reality will reveal private investment as the solution. But perhaps it will be too late by then and true sovereignty, understood as the power to face external interference in domestic affairs, will be truly diminished.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |