Regulatory | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Column: Mexican Natural Gas Business, Smartly Played, Could Help With Economic Recovery

Editor’s Note: NGI’s Mexico Gas Price Index, a leader tracking Mexico natural gas market reform, is offering the following column as part of a regular series on understanding this process, written by Eduardo Prud’homme.

Prud’homme was central to the development of Cenagas, the nation’s natural gas pipeline operator, an entity formed in 2015 as part of the energy reform process. He began his career at national oil company Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex), worked for 14 years at the Energy Regulatory Commission (CRE), rising to be chief economist, and from July 2015 through February served as the ISO chief officer for Cenagas, where he oversaw the technical, commercial and economic management of the nascent Natural Gas Integrated System (Sistrangas).

The opinions and positions expressed by Prud’homme do not necessarily reflect the views of NGI’s Mexico Gas Price Index.

A month has passed since the start of phase 2 of the Covid-19 pandemic response in Mexico, during which time the government has promoted measures of social distancing and limited nonessential economic activity. The truth is that even before that, many companies and schools began the practice of working from home. As a result, the patterns of economic production and consumption have been gradually changing, and their effect on the energy sector is beginning to be significant.

With the start of the second quarter in Mexico, economic activity usually leaves behind the sluggishness of the colder start of the year. In a typical year, once the Easter holiday period has ended, the demand for electricity begins to rise and this leads to a higher gas consumption used for generation because of warmer weather.

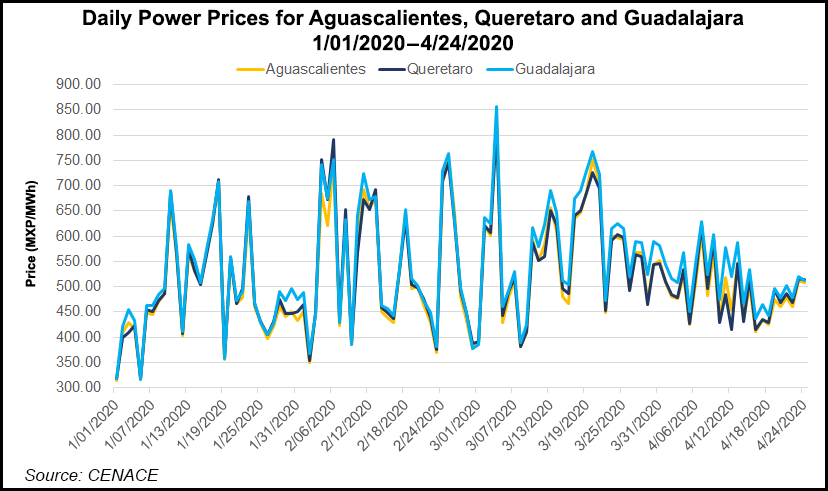

Cenace data on electricity demand is reported with a couple weeks of lag, so it is not yet possible to fully quantify the demand effect attributable to the Covid-19 restrictions. However, by contrasting the available data from last year, it’s possible to estimate a drop of around 5% in power consumption. This decrease is already notable in the gas system.

The measurement data for March is not yet available in the Cenagas electronic bulletin, but confirmed volumes for the extraction points are. The behavior of the nodes associated with electricity generation plants is not uniform, but consumption centers where gas decreased from March to April is around 20%. In addition, electricity demand in Sistrangas is 12% lower than the levels normally observed since the capacity reserve regime began.

To measure effects on the integrated system, it is important not to lose sight of the fact that the South Texas-Tuxpan marine pipeline has been replacing transportation within Sistrangas, but significant volumes enter Sistrangas through the Montegrande interconnection. Even with these considerations, demand for gas from the electricity sector has decreased, and this is attributable to the pandemic.

The decrease in gas demand is also evident in the industrial sector. On average, the central areas of the country and in the Bajío, where there are numerous industrial users, show a downward trend compared with last year, and in comparison to the previous quarter. In the industrial area from Puebla to Querétaro, consumers have stopped taking 10-20% of their normal gas from the Sistrangas. Since such volumes are small at each extraction point, the added effect is not as pronounced, and its operational consequences are minimal. An example of this situation is the extraction associated with the Fermaca-owned pipeline, Tejas Gas Toluca, which supplies the city of Toluca, west of Mexico City. The volume transported this month has fallen 12 MMcf/d from March, a small volume but significant for a gas pipeline that usually transports 70 MMcf/d.

Similar data can be found when analyzing other areas of the country. In the city of Saltillo, gas consumption in April is down 17% from March. Gas deliveries to an industrial profile distribution zone in Monterrey have decreased 12% in the same period. In the southeastern part of the country, within the Minatitlán and Pajaritos area, the decreases are around 30%. The volume transported in one of the systems of Sistrangas, Gasoductos del Bajío, is almost 10% off. The explanation is very simple: companies have decreased their gas consumption because they have reduced their production.

The coronavirus has exaggerated the sluggishness of the economic performance since the start of the government of President López Obrador. The partial closure of activities implies a reduction in the income of many companies, which leads to layoffs and even bankruptcies in some instances. Private initiative has clamored for a plan for economic reactivation by the government, but such a plan does not appear to be happening. In the last week, the president has said he is sticking to his original investment plans, which include converting a military base into a commercial airport serving Mexico City; constructing a rail system through a tourist corridor in the Yucatan peninsula; and the constructing the Dos Bocas refinery.

The controversy around continuing these projects has grown as the public would like to see financial resources committed to medical equipment to attend to the pandemic, as well as to alleviate the effects of the shutdown that may extend through May.

That being the case, energy demand will remain stagnant and could even drop further. Ironically, in a year in which the gas infrastructure conditions have improved substantially, the use of the new transport capacity will not be used as planned. The economic consequence is serious, although its implications are still not being felt. The fact that volumes are lower does not change the financial obligations of the pipelines in operation, however. Fixed costs will be diluted on a lower rate basis, and they will have to be paid.

In terms of medium-term effects, the disruption from the pandemic may see a rebound “J” curve in consumption. The question is the magnitude of the recovery. The Finance Ministry will see less collections from the drop in economic activity and in oil revenues. Meanwhile, social demands for health and rehabilitation will mount.

In this framework, and in the prevailing logic of astringency in spending, the López Obrador government has tools available to improve the energy outlook.

CFE has a contracted capacity to transport natural gas that far exceeds its requirements associated with electricity generation. It has more than 9 Bcf/d capacity, but demand of only about 3.5 Bcf/d. State oil company Petroleos Mexicanos (Pemex) mainly markets gas that is not produced in its fields. CFE and Pemex, in their oligopolistic intermediation, appropriate an income to the detriment of the well-being and productive capacity of gas users. The commercial margins charged by both companies do not always reflect the opportunity cost of supply at all points of consumption in the country. Hoarding capacity on import pipelines is a major barrier to entry that prevents gas users from effectively reaping the benefits of being a neighbor to Texas, the cheapest gas-producing area in the world.

CFE and Pemex have served as anchor clients for most of the existing gas pipelines in the country. However, in a scenario that is shaping up to be difficult for public finances, it is sensible to understand contractual commitments not only as a source of long-term liabilities but as an opportunity to take advantage of the value of the assets acquired.

Part of the transport capacity in Sistrangas, in the marine pipeline, together with the pipelines that make up the Wahalajara line and in other private systems, may well be placed into a secondary market. That would provide liquidity to the natural gas market and provide state companies with economic resources to alleviate their spending pressures. In a secondary market, with adequate rules and limited periods, both Pemex and CFE can obtain margins above the conventional rates paid to the owners of the pipelines and at the same time retain the ownership of the capacity by giving a temporary character to assignments. This exercise, with due foresight, can also contribute to improving energy security to Mexico, providing of course the nebulous concept of “energy sovereignty” publicized by the government is seen in a new light.

The Mexican government can broaden the discussion regarding the regional energy balance in North America. The press and social networks spent much time debating Mexico’s participation in the agreement to reduce crude output by the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries and their allies. Supporters and opponents of the government clashed in their interpretation of the events. Removing the political noise, it is clear that Mexico has a different geopolitical weight in global energy markets if it participates as a solitary agent, or if it plays together with its partners in the North American region.

In this context, CFE’s excess capacity may be used to improve the economic recovery of the region. Ports on the Mexican coast may be the gateway to move Waha gas from West Texas to the Pacific Rim. The contracted capacity, which today is a liability for being idle, could inject dynamism into Mexico’s coffers and the natural gas industry. The use of the pipelines, and with it their amortization, can improve their performance in the long term by not being limited to internal consumption and their respective fluctuations.

Put like this, the gas network’s medium and long-term future may continue to be operationally and financially viable without being a fiscal burden in an environment of recovery from the economic crisis. The opportunities are waiting to be seized. A little less ideology and more imagination can create a lot of value for the economy, but it is important to change the nuance of energy policy. An opening of this type would give access to more and new players, and would undoubtedly receive the applause of many, inside and outside the country.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |