Column: Don’t Let Start of Mexico’s Largest Import Pipe Halt Advancing Modern Natural Gas Market

Editor’s Note: NGI’s Mexico Gas Price Index, a leader tracking Mexico natural gas market reform, is offering the following column as part of a regular series on understanding this process, written by Eduardo Prud’homme.

Prud’homme was central to the development of Cenagas, the nation’s natural gas pipeline operator, an entity formed in 2015 as part of the energy reform process. He began his career at national oil company Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex), worked for 14 years at the Energy Regulatory Commission (CRE), rising to be chief economist, and from July 2015 through February served as the ISO chief officer for Cenagas, where he oversaw the technical, commercial and economic management of the nascent Natural Gas Integrated System (Sistrangas).

The opinions and positions expressed by Prud’homme do not necessarily reflect the views of NGI’s Mexico Gas Price Index.

On Sept. 17, the 800-kilometer, 2.6 Bcf/d Sur de Texas-Tuxpan marine pipeline began operating, and in doing so became the pipe with the most import capacity into Mexico. The media attention has surpassed any other pipeline project in the country, including the Ramones system. The climax and outcome of contract negotiations with anchor client, the Comisión Federal de Electricidad, or CFE, was talked about often nationally by President López Obrador. But no one is talking about the pipeline’s commercial and operational implications.

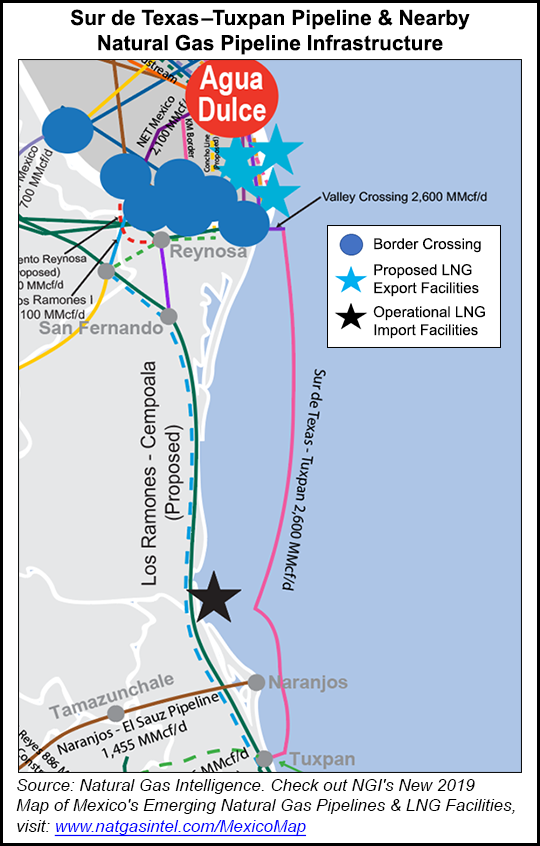

Marine Infrastructure of the Gulf (IMG), the official name of the project as set out in the permit granted by the CRE, starts in Brownsville, TX, where it connects to the Valley Crossing Pipeline. It then travels underwater to the port city of Altamira, where the pipeline can deliver about 190 MMcf/d of natural gas to the 800MW Altamira V power plant. There is no connection to the Sistrangas here, despite its proximity. The reason for this is that the anchor client is the CFE, not Cenagas, so both the design and operating philosophy of the marine pipeline are in the interests of the former, not necessarily those of the market as a whole. For practical purposes, Altamira and its surroundings will see limited operational flexibility.

The pipeline then traverses back to sea, and continues south. Around Tuxpan, it comes ashore and splits in two. Heading north, it reaches “Los Higueros” from where gas flow can continue through the Naranjos-El Sauz pipeline, owned by TC EnergÃa. IMG gas will replace the flow that has come from the Sistrangas to cover demand of the 1,135 MW Tamazunchale combined-cycle power plant and to complement gas supply for CFE through the interconnection known as Pedro Escobedo. The entire pipeline capacity of about 800 MMcf/d will be used. In physical terms, the gas that feeds Naranjos-El Sauz cannot come from Sistrangas, which limits supply options for users other than CFE in Tamazunchale.

Heading south, the IMG pipeline delivers gas to two pipeline systems. In Montegrande, an interconnection with the Sistrangas will allow Cenagas to receive up to 0.5 Bcf/d. The marine pipeline will also connect with another TC system, the Tuxpan-Tula gas pipeline. According to Cenagas’ 2015-2019 Five-Year Gas Pipeline Plan, this system will receive about 900 MMcf/d of gas from Texas. Along a sequence of gas pipelines, the gas would cross from coast to coast to supply CFE generation plants in the Central, BajÃo and western parts of the country.

But an important segment of the Tuxpan-Tula pipeline remains stalled because of various reasons. Thus, in the foreseeable future, the gas that transits from IMG to Tuxpan-Tula will only serve the Tuxpan II and Tuxpan V generation plants, a volume of up to 250 MMcf/d.

According to electronic bulletin board data, as of last Thursday (Sept. 19), there was slightly more than 600 MMcf/d confirmed for transport by the marine pipeline destined for Pedro Escobedo. The expectation is that in the coming weeks, the interconnections at Montegrande and the extraction point in Altamira will begin to be used.

This new flow is good for the Mexican gas system, and promising in solving operational problems. In terms of continuity of service, the inclusion of a new interconnection diversifies supply. In terms of economic efficiency, U.S. gas supplied to the Gulf of Mexico from the Agua Dulce hub in South Texas is clearly cheaper than the liquefied natural gas (LNG) that is regasified at the Altamira and Manzanillo import plants. However, from the perspective of energy security, one of the concerns reiterated by the government has reason to be reinforced: Mexico’s dependence on gas from Texas intensifies.

The marine pipeline also poses a series of complications that will require new operational criteria, important capacity management measures, and even additional projects.

Until the marine pipeline went into operation, Mexico had seven points of natural gas connection with Texas. Five of them are direct international interconnections with integral systems. In the Reynosa-Arüelles areas, Cenagas offers gas transportation routes from the Tennessee Gas Pipeline Company, Texas Eastern Pipeline, Energy Transfer LP and Kinder Morgan Inc. border systems. The gas received by these points goes down the Tamaulipas gas pipeline owned by Ienova and continues through the 48-inch diameter pipeline owned by Cenagas. There is little gas that can move from that border region to Los Ramones and the vicinity of Monterrey.

Under certain consumption conditions between the compression station Los Indios and Tuxpan, it’s quite possible that confirmations of 500 MMcf/d by Montegrande would overpressure the pipeline, making it necessary to cut off the flow of nominations that are above daily maximums of primary injection in Reynosa, Argüelles and Burgos. If a flow cut occurs at these points on firm capacity, the cause would be preference being placed on the marine pipeline gas injected into Montegrande.

Today, imports into Camargo from NET Mexico remain the largest injection of natural gas into the Mexican pipeline system. But at 2 Bcf/d, this huge project, which is almost always fully utilized, has moved to second place in nominal import capacity. A slight variation in the integrated volume that NET Mexico carries will lead to a cascade of needed adjustments that puts systemic balance at risk and, in the absence of operational storage, means LNG would be needed for adequate pressure.

Half of the volume of natural gas imported into Mexico stays in the northern part of the country, from Monterrey to southern Chihuahua, with transportation provided by Gasoductos del Noreste and the National Gas Pipeline System. The other half travels through the Ramones system, serving a number of industrial users and electricity generators in the states of Nuevo León, San Luis PotosÃ, Guanajuato and Querétaro. The remaining flow is still significant when it reaches the interconnection with the National Gas Pipeline System in Apaseo el Alto.

Thanks to this gas, from mid-2016 onwards there haven’t been any critical alerts in the BajÃo area and in the states of Michoacán and Jalisco. This should not be affected by the marine pipeline. However, the continuation of the gas flow through the Naranjos-El Sauz pipeline was previously intermittent and marginal, and is very likely to see flows higher than 0.5 Bcf/d into Pedro Escobedo, where Naranjos-El Sauz interconnects with the Sistrangas.

This injection will improve the availability of gas for generation in various plants in Querétaro and Guanajuato. But it will also replace in part the volume that the Ramones phase II pipeline delivered in the area. If no additional consumption occurs between San Luis Potosà and Querétaro Industrial Park, a domino effect will impact flows upstream. Like the volumes imported by Reynosa, it may be necessary to cut off natural gas flows that are above the maximum daily primary injection capacity in Camargo. It will be important to understand the relationship of gas reception confirmations from Net Mexico and from Pedro Escobedo. Just as important will be to understand the relationship of these behaviors with the way capacity is reserved on the routes that depart from these points.

Meanwhile, the suspension of construction on the Tuxpan-Tula pipeline, if drastic measures are not taken, can mean leaving about 1 Bcf/d of capacity on the marine pipeline idle because the nonavailability of the pipeline as planned leads to a fraction of the marine pipeline ending in a dead end. The reason for the Tuxpan-Tula pipeline was to avoid saturation of the Sistrangas in central Mexico. To maximize IMG’s capacity, CFE will need to send gas to central parts of the country via Naranjos-El Sauz. The effect will be a blockage of the systems because of a saturation of flows in the east-west system.

Another issue is how to manage capacity. The way firm capacity was offered in the first open season conducted by Cenagas was based on prevailing conditions resulting from the start of the Ramones project. The 6.3 Bcf/d capacity was calculated from a hydraulic model that represented these flow conditions. It is clear that after a couple of years of physical adjustments and given the entry into operation of the marine pipeline and the prospects of having new injection capabilities from the Fermaca pipeline system, Waha-Guadalajara, it’s pertinent to review the capabilities of the Sistrangas and its routes. This analysis should be the first step in a process of reallocating routes through a transparent and competitive mechanism.

There also needs to be a revision of the Sistrangas rate design. The new transport fee list must include zoning that is in harmony with new routes.

The energy sector must advance in consolidating the capacity system, including open seasons, and advance in infrastructure development. On an individual level, energy security means that the probability that a user’s supply is interrupted is zero. The relative abundance of marine pipeline gas should not hide the need to strengthen the gas network. This must occur at the level of following industry practices. All participants must also be active promoters of the creation of new services — parking, loaning, backhauling — and the development of strategic projects such as operational storage, the development of physical hubs, and more interconnections between systems.

In sum, the marine pipeline should not be seen as the panacea of the gas system, but rather a milestone toward the development of a robust and modern market that requires yet more investment.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 |