Markets | E&P | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

China Facing Headwinds in Goal to Double Natural Gas Output

China is forecast by some prognosticators to become the world’s third largest natural gas producer by 2027 but imports still could increase because of lower shale and coalbed methane (CBM) production.

“Production is still expected to double from 149 billion cubic metres (bcm) in 2018 to 325 bcm in 2040, but that is 39 bcm lower than its previous outlook,” Wood Mackenzie Ltd. consultant Xueke Wang said in a recent report. “While we are positive on conventional and tight gas output, the long-term growth of CBM and shale production looks to be challenging.”

Shale gas production grew to 10 Bcm in 2018 from about zero in 2010 and now accounts for around 7% of total output. In addition, comprehensive costs per well in the Fuling field operated by China Petroleum & Chemical Corp., aka Sinopec, have fallen by about 40% since the first exploration wells in 2010 and are 25% below the first commercial wells in 2014.

However, success at Fuling may be difficult to duplicate because of geological heterogeneity, according to Wood Mackenzie. Even PetroChina Co. Ltd.’s three shale gas projects in the same basin have not been achieving the same economics as Fuling.

Other shale gas-rich basins in China, including Ordos and Tarim, aren’t expected to be commercialized in the mid-term, while the desert environment and limited infrastructure is adding to the list of challenges.

Beijing-based Caixin Group said about half of China’s shale reserves are buried at least a prohibitive 1.86 miles (3 km) down. For the 19 firms with exploration contracts, an initial failure to discover extractable resources may have made persuading investors to spend more on funding more difficult, analysts said.

Since shale formations in China are usually deeper and more tectonically fractured than U.S. shale plays, operators face higher drilling costs and difficulties in maintaining wells.

Beijing has reduced resource taxes on shale gas and the government has urged its oil and gas producers to upgrade drilling plans. This year Sinopec is spending $8.3 billion on shale exploration, a 41% increase over last year, with a substantial amount earmarked for an expansion of its Fuling operations.

Challenges also remain for CBM development. Since 2017, 22 CBM blocks have been offered for bidding to national oil companies (NOC). Yet, commercialization of these blocks has been slow since many were of medium to low quality. More important, the overlapping of mining rights between CBM and oil and gas has obstructed CBM’s development, according to Wood Mackenzie.

With output limited by project economics, and technical and regulatory conundrums, CBM production is expected to reach 15 bcm in 2040, a 40 bcm reduction from a previous forecast.

According to the National Energy Administration, the country has 36.8 trillion cubic meters of CBM reserves, the third largest after Russia and Canada.

China’s tight gas development has proven more successful because of mature technology, reliable geological data and overlapping distribution with conventional gas.

Positive developments also are seen in China’s conventional gas production. In 2018, domestic gas production in China increased 7% year/year, mainly from conventional plays in the Ordos, Sichuan and Tarim basins. To help reduce gas import reliance, China’s NOCs have formulated seven-year plans (2019-2025) to raise budgets and stimulate upstream exploration.

PetroChina plans to allocate $700 million annually on venture exploration. China National Offshore Oil Corp., aka CNOOC, plans to increase exploration activities to double proven reserves by 2025.

Still, while Wood Mackenzie expects overall output to double by 2040, a source who works with an oil major in China told NGI that the 325 bcm projection by 2040 appears overly optimistic.

“Even though CBM, shale and tight gas finally received subsidies this year, CBM targets were never achieved and I have a difficult time believing shale gas targets will be met without major reforms in domestic gas markets and gas prices,” he said.

A recent Oxford Institute of Energy Studies report said the Chinese government faces a challenge of choosing between low domestic gas prices to stimulate demand and improve the environment or high prices to encourage domestic production.

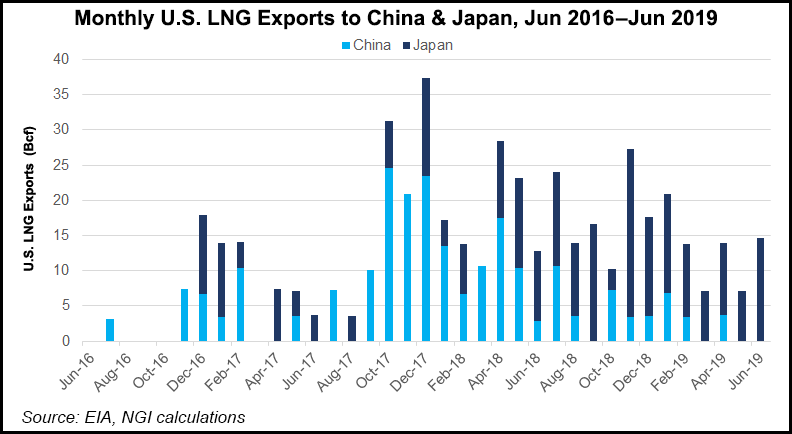

China has 21 LNG import terminals in operation, with a total capacity of 80 million metric tons/year. Japan by comparison operates more than 30 import terminals, including expansions and satellite terminals.

China’s NOCs have also invested heavily in LNG production projects globally, including in Australia, East Africa, Western Canada, and in Russia’s Arctic. The country’s producers have also signed numerous long-term LNG offtake agreements around the world.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |