Can the United States Really Send More LNG to Europe?

The United States has a chance to deliver on its pledge to move more liquefied natural gas (LNG) to Europe, but it won’t be easy in a tight global market that is expected to be short on supplies in the coming years.

The White House and European Commission offered few specifics about how the U.S would send another 15 billion cubic meters (Bcm) of LNG to the continent this year and 50 Bcm annually through at least 2030. The White House pledged to expedite approvals for LNG projects, which take years to build.

In a joint statement Friday, the governments said they would work with international partners and ensure demand for the super-chilled fuel. The continent is aggressively trying to reduce its reliance on Russian energy imports amid a conflict in Ukraine that has threatened supplies.

“I’m not sure what the mechanism is in the short-run to accomplish that, aside from Europe being the best market, or Europe being willing to pay to essentially buy LNG away from Asia-Pacific buyers,” said Poten & Partners Jason Feer, global head of business intelligence.

A Fighting Chance

In theory, the United States could hit the aspirational targets. The country has driven global LNG supply growth for years, putting it in a position to better aid Europe as it looks to break away from Russia. U.S. terminals have been operating at or near capacity for months.

If the Calcasieu Pass LNG terminal enters full service this year as scheduled, the United States would have the largest peak LNG export capacity in the world at nearly 14 Bcf/d, or roughly 140 Bcm/year. The bulk of Calcasieu Pass’ supply contracts were signed with European buyers and global portfolio players.

“Those contracts should begin this year, and if they do, Europe will for certain get additional cargoes,” LNG Allies CEO Fred Hutchison told NGI.

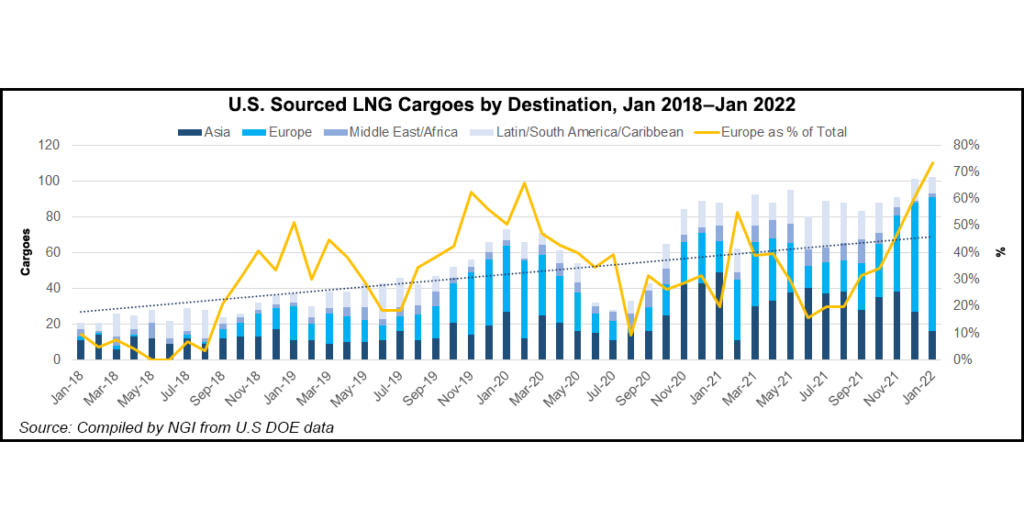

The U.S. supplied Europe with 25 Bcm of LNG last year, or roughly 35% of its peak capacity at the time. U.S. exports to the continent have surged this year, accounting for about 70% of all deliveries as European prices have soared amid a supply shortage and fears that Russia could cut off flows to Europe in retaliation for Western sanctions.

Europe imported about 45% of all its natural gas imports from Russia in 2021 and is aiming to cut them by two-thirds before the end of the year and gain independence from the pariah state before 2030.

Assuming the U.S. can deliver 50 Bcm to Europe after 2022, that would amount to about 35% of the peak capacity that’s expected to come online by the end of this year – roughly in line with the proportion of volumes purchased by European buyers in 2021.

“If I were asked to guess, I’d figure it would be north of 50% next year,” Western LNG CEO Davis Thames told NGI, referring to the amount of U.S. cargoes that are likely to go to Europe. “The economics will be overwhelming, and there is always coal and oil substitution in Asian markets to replace LNG that gets repositioned in Europe.”

After that, the outlook is murkier. Along with Train 6 at Cheniere Energy Inc.’s Sabine Pass terminal in Louisiana, Calcasieu Pass adds another 20 Bcm of U.S. capacity this year. But American volumes aren’t expected to grow all that much again until late 2024 or 2025 once the Golden Pass LNG terminal comes online in Texas.

At that point, the United States would have a peak capacity of 16.3 Bcf/d or roughly 168 Bcm. There are another 17 applications for additional U.S. LNG capacity pending approval at the Department of Energy.

Feer told NGI that Poten expects just 28.7 Bcm of new LNG supplies to come online across the world this year. The total drops to about 14 Bcm annually between 2023 and 2025.

“There is virtually nothing anyone can do about that just in terms of the amount of time it takes to build an LNG plant,” he said. “The absolute minimum is three years, but it usually takes four or five.”

Sold Out

Other top suppliers such as Australia and Qatar are largely sold out. Moreover, 85% of U.S. LNG volumes are already spoken for under long-term contracts that don’t restrict destinations. In other words, U.S. export terminal operators don’t have control over their volumes, the LNG buyers that come from overseas decide where those shipments go.

“U.S. LNG exporters are not a charity, so in the end, they will send more volumes to whoever pays the highest price,” Rystad Energy’s Carlos Torres Diaz, head of gas and power markets, told NGI.

Since late last year, European natural gas prices have largely been the world’s priciest, which has attracted an influx of LNG cargoes. Historically, however, Asia has been the premium market. Warmer weather and strong storage inventories ahead of winter have diminished competition from Asian buyers in recent months.

But, Feer said that isn’t likely to last.

“For a lot of Asian buyers, if they don’t take natural gas, if they don’t take LNG, they may not have any other options,” Feer said. “This idea that Europeans are going to take it all, runs into the reality that Asian buyers are highly motivated buyers as well.”

Although Asia has moved some cargoes to Europe in recent weeks, the West’s effort to divert more supplies from the region has largely fallen flat given how coveted the super-chilled fuel is in Asia.

Europe Union (EU) leaders have outlined a series of proposals to boost energy supplies on the continent, but LNG is one of the few stop-gap measures the country can utilize to cut its consumption of Russian gas in the short-term. The continent is aiming to reduce Russian gas imports from 155 Bcm last year to 101.5 Bcm by the end of 2022.

Further complicating matters to bring in more of the fuel is available capacity at regasification terminals that take in cargoes. European Import terminals have been running above 90% capacity this winter and storage inventories remain below the five-year average.

There is not enough infrastructure to push additional LNG into the grid or storage during times of peak demand. Additionally, excess import capacity in Southern Europe cannot be utilized for other parts of the continent because there is not enough pipeline capacity to move more supplies north.

An effort is underway to build more import terminals or bring in floating regasification and storage units offshore. EU leaders have also proposed filling storage to 80% of capacity by the beginning of November and more aggressively in the coming years.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |