NGI Archives | NGI All News Access

British Columbia Ready to Topple Alberta As Top Gas Supplier

When natural gas markets make a comeback, an extended foray into horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing shows British Columbia will be ready to fulfill expectations of taking over Alberta’s fading role as Canada’s top source of supply growth.

Sustained success with the drilling and well completion methods imported from the United States is described in a new geological atlas that the British Columbia Oil and Gas Commission (BCOGC) is circulating to industry as a treasure map to lure investment in the province. The high expectations, expressed by an array of official observers from the National Energy Board (NEB) to BC Premier Christy Clark, are echoed in a new 25-year industry forecast from the Conference Board of Canada, titled “The Role of Natural Gas in Powering Canada’s Economy” (see Daily GPI, Dec. 18).

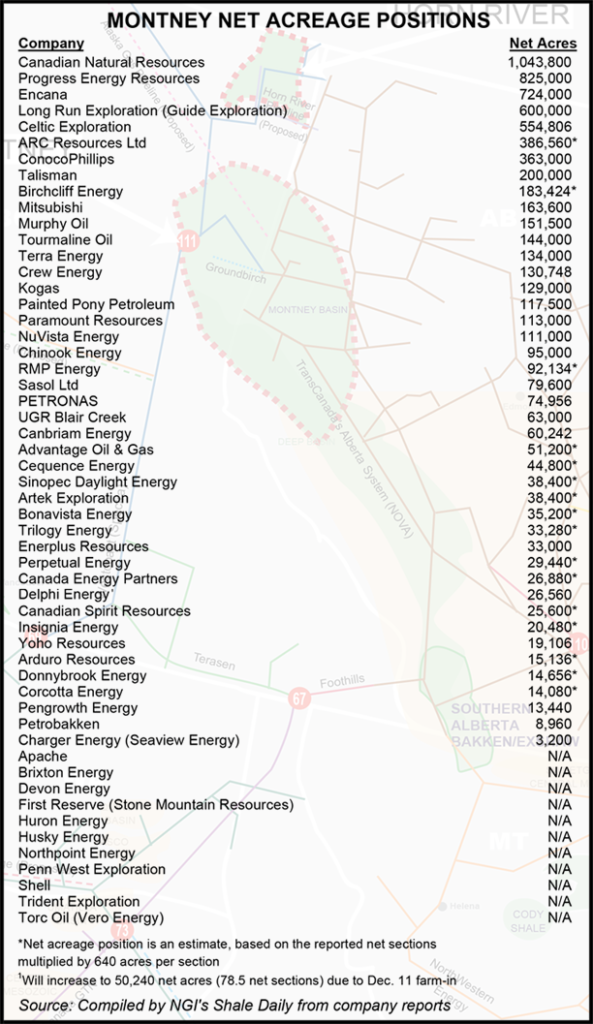

The atlas is an earth sciences and economics portrait of a formation known as the Montney, which carpets a 26,000-square-kilometer (10,000-square-mile) band of northern BC at varying depths. The subterranean zone is up to 300 meters (984 feet) thick and has been well known to generations of industrial explorers in Alberta as well as BC, as steeped in gas and liquid byproducts but too dense to tap with conventional vertical wells.

Titled “Montney Formation Play Atlas NEBC,” the provincial treasure map is an early result of a collaboration to document unconventional resources in BC and Alberta by the BCOGC, the NEB and Alberta’s Energy Resources Conservation Board.

BC’s especially rich share of the Montney forms an oblong strip, angled southeast to northwest, which starts at the province’s border with Alberta and straddles the Alaska Highway from its Mile One at Dawson Creek into woods and muskeg swamps about halfway to remote Fort Nelson, a short hop from the Yukon and Northwest Territories.

Until the first use of horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing on the tough target in the Dawson Creek region in 2005, the BCOGC atlas said total cumulative Montney production by conventional vertical wells was a paltry 25 Bcf.

As of mid-2012, about 1,100 wells — all employing the shale gas development techniques imported from the United States — increased cumulative BC Montney production 52-fold.

The formation’s total output in BC was rising by 1.5 Bcf/d as the new generation of horizontal wells produced as much as all of their vertical ancestors about every two weeks.

Montney activity has swiftly grown to 41% of total provincial output and become “the single most important gas producing horizon [geological layer] in British Columbia,” said the BCOGC.

Industry interest has stayed high despite poor gas prices on glutted North American markets because BC’s share in the Montney has a rare attraction for the province. Parts of the deposit are rich in hydrocarbon liquid byproducts, known as condensate or natural gasoline, which fetch prices close to or at times exceeding the value of oil.

Thanks to Montney wells, annual BC production of natural gas liquids (NGL) grew by 33% in four years to 7.6 million bbl in 2011 from 900,000 bbl in 2007, said the BCOGC. The 2011 NGL total exceeded BC’s oil production from all sources in the province combined, the commission said.

Just how great the area of the liquids-rich part of the deposit is remains unknown, and the commission makes no attempt to guess at the volume that might eventually be tapped. But sketchy outlines in the BCOGC atlas of the richest Montney zones, made possible by limited industry disclosures to date, suggest the potential is large.

The new Canadian gas industry overview compiled by the Toronto-based Conference Board of Canada attempts to translate BC’s potential into dollars and jobs. In its recently released report, the business agency said upstream gas exploration and production investment in BC has potential to add up to a total of C$139 billion over the period 2010-2035.

The field activity will increase BC’s production by 66%, towards 2 Tcf per year, as soon as 2020, the conference board said. The BC growth projections are intended to err on the conservative side by discounting the apparent scale of the emerging boom in northern Pacific Coast export terminals for liquefied natural gas (LNG).

The Conference Board based its numbers on limited expectations that the BC coast projects will eventually reach annual output of overseas LNG tanker loadings in a range of 20 million tonnes, or 1 Tcf, about half the combined total of proposals to date.

Nearly as much gas exploration and production investment is projected in Alberta. But the province’s output will still shrink by about 25% as of 2020 due to natural depletion of half century-old former mainstay reserves, the Conference Board said.

With planning for the next round of growth in Canadian gas development focused on Asian exports, the Conference Board predicted that current trends toward a long-term switch in North American energy trade patterns will continue. Canada’s role as a pipeline exporter to the United States will shrink. U.S. suppliers will turn the tables by taking a growing share of Canadian gas markets. “Consumers in eastern Canada are likely to rely more and more on imported U.S. natural gas as shale development continues and pipeline capacity expands,” the board predicted.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |