LNG | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Panelists: LNG Exports Won’t Lead to U.S. Price Spikes

Warnings from some who claim sending too much U.S. natural gas overseas could cause severe domestic price spikes are short-sighted and don’t account for global supply and demand dynamics, or the cumulative effect exports could have on the U.S. economy, according to a group of panelists.

With shale production expected to continue climbing over the next two decades (see Daily GPI, May 8), James Balaschak, a principal at Deloitte LLP, said ample gas supplies will not only meet demand overseas, but also have a significant impact on keeping prices low in the U.S.

“There’s a big concern in this country that if we export liquefied natural gas (LNG), the price is going to go through the roof,” he said at the Shale Insight conference in Pittsburgh Wednesday. “The price increases in the U.S. will be marginal under our models. Average Henry Hub prices come up about 15 cents. The decline in importing countries is almost a dollar. So the exports will have a real material effect. This effect of reducing export prices will actually put pressure on how much we can export. It’s a dynamic supply and demand model.”

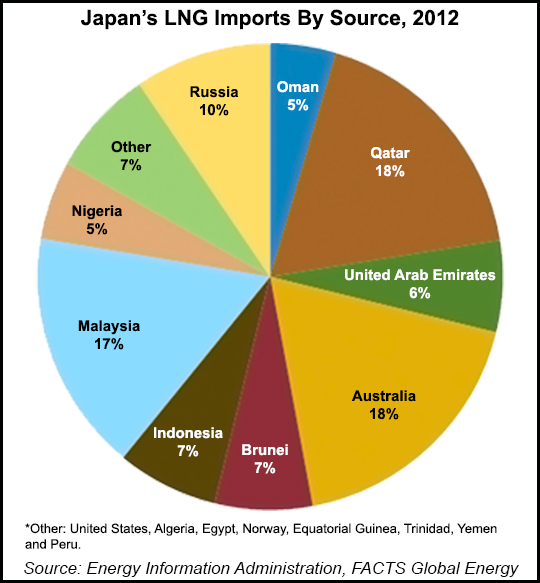

Balaschak said Deloitte analyzed various economic models and found that if the U.S. exports 6 Bcf/d to Asia and 6 Bcf/d to Europe, it would be enough to break natural gas’ relation to oil price indexation in places like Japan, where natural gas has sold for more than $16/MMBtu (see Daily GPI, Jan. 10, 2013). That, on its own, he said, could at the very least bring Japanese prices somewhere near those in the U.S.

“We have to substitute. What is happening here is quite clear; the natural gas is becoming much more important for Japan,” said Kazuyuki Onose, senior vice president of Sumitomo Corp Americas. “A couple things I can tell you is that up until 2008, the prices of natural gas were similar to the U.S. in Japan, but from 2009 on, you see a big difference in the diversion of prices across Europe, the U.S. and Japan. Where is this coming from? I it’s quite clear. It’s the shale gas revolution.”

Japan has expressed an interest in importing roughly 20% of its natural gas from North America as early as 2016. Kazuyuki said imports from the United States could help Japanese gas drop closer to $10/MMBtu.

Sumitomo, which is actively involved in global trading and investing in everything from noodles and missiles, to energy and chemicals, has been growing its footprint in the U.S. onshore in recent years. It has joint ventures with Rex Energy Corp. in the Marcellus Shale and Devon Energy Corp. in the Permian Basin (see Daily GPI, Sept. 1, 2010; April 2, 2012). It has also signed agreements to buy U.S. LNG from export facilities, such as Cheniere Energy Inc.’s Sabine Pass and Dominion Cove Point LNG LP (see Daily GPI, April 8, 2013; Feb. 21, 2011).

Kazuyuki said that ever since the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster in 2011, when a tsunami triggered a meltdown at three of the plant’s six reactors, Japan’s already growing natural gas imports have ballooned (see Daily GPI, April 2, 2011).

Nearly 50% of the country’s power supply currently comes from natural gas, he said. Last year, Japan also accounted for 88% of global LNG imports. He added that if the U.S. exports just 10 Bcf/d of LNG to non-free trade agreement countries, it could have a dominate 30% of the global market.

Trade associations representing manufacturers and regulated utilities, such as America’s Energy Advantage and the American Public Gas Association, have argued that increased LNG exports could lead to higher prices and risk availability (see Daily GPI, Sept. 23, 2013). But U.S. Rep. Bill Johnson (R-Ohio), whose district has benefited greatly from the Utica Shale boom, said the issue is not only about moving U.S. gas overseas.

“Every study we have seen would indicate that if there’s a cost increase, it’s going to be marginal in the scheme of things; it’s going to be manageable because you’re going to have to balance not just pricing, but all the other economic factors,” he said. “That’s one thing that gets us into trouble is that we look at these things so myopically.

“We put blinders on and we look at just one particular avenue of it, but you’ve got to look at the thousands of jobs that will be created; you’ve got to look at the international implications of what we’re talking about.”

Balaschak followed up on Johnson’s point by saying that an increase in American exports could eventually cut Russia’s Gazprom revenues by 18%, while decreasing gas prices by as much as 11% in Europe alone. The flood of LNG, he said, would make global prices more competitive and insulate the U.S. from severe price spikes.

A study conducted by NERA Economic Consulting in 2012 and revised in March found that expanding LNG markets could generate $86 billion in net benefits for the U.S. economy and create as many as 2.4 million jobs by 2035 (see Daily GPI, March 11; Jan. 11, 2013; Dec. 6, 2012).

The value added to the U.S. economy, combined with the geopolitical advantages more LNG exports could bring for the U.S., Johnson said, would offset any marginal domestic price increases.

“There’s a balance in looking at all this, and we have to be careful that we don’t throw out the baby with the bathwater over scare tactics about rising prices.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |