U.S. LNG Exports No Panacea for Europe, Report Finds

U.S. exports of liquefied natural gas (LNG) will strengthen Europe’s bargaining position with Russia and help create a more diverse global gas market, but they won’t solve the current crisis in Ukraine or free Europe from Russian gas, and they are unlikely to cause the Kremlin to change its foreign policy, according to Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy.

In a 60-page report, researchers Jason Bordoff and Trevor Houser predict U.S. LNG exports will boost Europe’s bargaining position with Russia, leading to contract renegotiations and ultimately lower natural gas prices. To support their prediction, they pointed to the effects of the U.S. shale gas boom — specifically, an expanded global gas supply that helps European consumers and hurts Russian producers, as LNG shipments previously destined for the U.S. are diverted elsewhere.

“The U.S. natural gas revolution has already undermined the profits of Russian producers and benefitted European consumers,” Bordoff and Houser said. “The displacement of 9.4 Bcf/d of LNG supply that resulted from the U.S. shale boom coincided with a period of sharply reduced European gas demand, due to the great recession in 2009 and the subsequent Euro crisis from 2010. Oil prices rebounded quickly following the crisis, but natural gas prices in Europe remained low, due in large part to this additional supply of LNG.”

The researchers added that the divergence between oil-indexed and spot natural gas prices “put considerable pressure” on Europe’s gas suppliers, especially Russia’s OAO Gazprom, which was initially reluctant to renegotiate contracts but eventually granted big discounts by linking a small percentage of the contracted volumes to hub prices.

Gazprom could also get pinched by the European Commission, which launched an antitrust probe against the company in 2012. A ruling against Gazprom could further weaken its market position in Europe by requiring it “to eliminate any remaining destination restrictions, or possibly even to replace oil-indexation with hub-based pricing formulas in all of its long-term supply contracts. The antitrust case may also result in substantial fines of up to 10% of the company’s annual revenues in the markets in question.”

According to the researchers, Morgan Stanley estimated that Gazprom could be fined as much as $1.7 billion. But they added that the company would likely appeal an adverse ruling to the European Court of Justice, which would delay a final ruling for several years.

Bordoff and Houser said U.S. LNG export terminals would operate “under a fundamentally different business model” than liquefaction terminals anywhere else in the world, with contract terms that may create flexibility and liquidity in the global marketplace. “The advent of U.S. tolling-type contracts may provide the global LNG market with more liquidity and buyers with more flexibility than the historic alternatives, and shift the balance of power from gas producers to consumer,” they said.

“Despite challenges with U.S. LNG exports, it is entirely possible that additional export capacity could get approved and built, and that total U.S. LNG exports could exceed the volumes already approved, or even potentially the 14.5 bcf/d Russia currently sells to members of the European Union.”

But the researchers warned that even if the U.S. proceeds with LNG exports, they would be years away and would not hit the marketplace soon enough to affect the current geopolitical crisis in Ukraine. Also complicating matters is the fact that European LNG infrastructure won’t allow imports to replace Russian gas in Eastern and Central Europe.

“European LNG regasification capacity is theoretically sufficient to displace all Russian imports with LNG, but all currently operational LNG import terminals are located in Western and Southern Europe,” they said. “Central and Eastern European countries are only now beginning to develop LNG import terminals in the Baltic Sea region.”

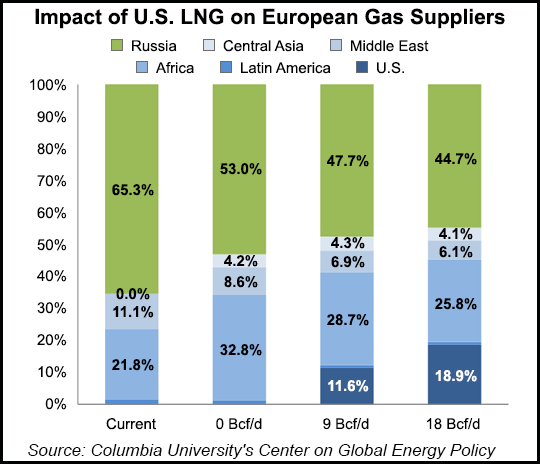

Under a model that envisions 9 Bcf/d of U.S. LNG exports to Europe, Russia would still supply 47.7% of Europe’s natural gas. Even if the exports were doubled to 18 Bcf/d, Russia’s stake wouldn’t budge much (44.7%).

Europe is tied to Russian gas because “it is relatively cheap and will likely remain competitive in the European market for the foreseeable future…While Europe has the physical ability over the long-term to replace all the gas it currently buys from Russia, such a move would require significant political intervention and is highly unlikely to occur only on commercial grounds.

“Gazprom appears to be sensitive to such political risk, and in its recent cutoff of supplies to Ukraine is walking a fine line between trying to exert its energy leverage without undermining its reputation as a reliable supplier.”

The researchers added that Europe will still be under the yoke of Russian gas imports for several years because they signed long-term gas contracts that are difficult to get out of. “Such obligations will continue to require Gazprom’s customers in OECD [Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development] Europe to take delivery of at least 10 Bcf/d of Russian gas in 2020, and more than 9 Bcf/d until 2027,” they said.

Although oil and gas exports are both vital to the Russian economy, the country makes more revenue exporting oil than gas. In 2013, the country exported $356 billion in oil and gas, including $283 billion in oil and less than $73 billion on gas. The latter figure included $54 billion from European pipeline gas exports.

“Going forward, it is possible that natural gas’s share of Russia’s energy export revenue may rise as Moscow implements various tax reforms to encourage greater investment in its oil sector, particularly unconventional production, which could reduce the share of oil rents captured by the state,” the researchers said. “Expanded sanctions, if they continue to target oil rather than gas production, may have a similar effect.”

They added that while U.S. LNG exports could force Gazprom to lower its gas prices to Europe to stay competitive, “the total economic impact on state coffers is unlikely to be significant enough to prompt a change in Moscow’s foreign policy, particularly in the next few years.”

As of August, the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) has given conditional or final approval for seven projects to collectively export 10.52 Bcf/d of LNG to non-free trade agreement (FTA) countries (see Daily GPI, Aug. 14). The DOE also changed the process for reviewing applications to export LNG to non-FTA countries, beginning the final review once the project has completed the environmental review process at the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. An additional 27 Bcf/d of export capacity is still awaiting approval.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 |