Regulatory | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Enforcement Has a Pivotal Role at FERC, Fuels Chief Says

FERC’s enforcement division has grown from five to to 500 employees since the market meltdown in 2000-2001, staffing a market monitoring center that closely follows electric and natural gas prices, tracking apparent aberrations for any evidence of market manipulation. Last winter’s polar vortex didn’t make their job any easier.

The market monitoring center has become the “eyes and ears on the market,” for the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, Christopher Ellsworth, the fuels branch head in the Market Oversight Division, told the LDC Gas Midcontinent Forum in Chicago this week.

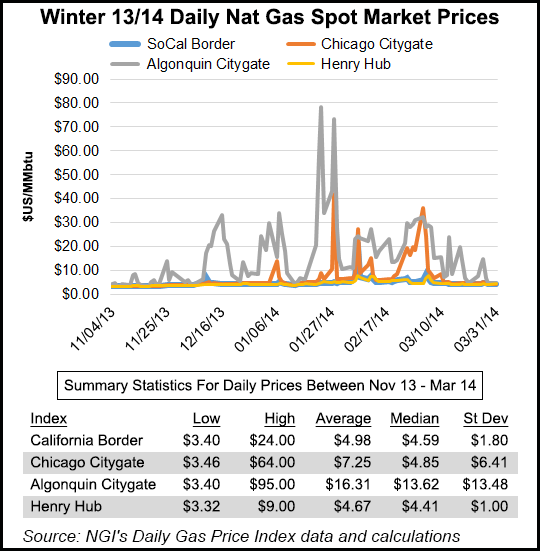

The polar vortex presented a challenge, Ellsworth said. One of the oddities noted was a moving around of the gas price spikes from the East (early January) to Chicago (Jan. 27) and onto the West in early February, and nevertheless, during that time Henry Hub prices never went much above $8, he said.

In the record cold, there was also a significant drop in gas-fired generation and a switch over to more coal-fired electricity in a number of areas. “This set off all sorts of bells, whistles and alarms about extreme high prices,” said Ellsworth, adding that FERC subsequently worked to try to determine why some buyers were willing to pay such high prices for gas.

Market oversight means working to separate the impact of market fundamentals from the possibility of anti-competitive behavior. Last winter “anyone who was outside of a nominated gas volume was subject to very high penalties, with multiples that tended to feed off one another, and also I think a lot of people had unrealistic expectations for [low] prices going into last winter,” Ellsworth said. “A number of players were caught short after delivering on their obligations, and having to get into the market in a hurry and pay very high prices as a result.”

Ellsworth outlined FERC’s ultimate goals since it was given strong enforcement and penalty authority by the Congress in the Energy Policy Act of 2005 (EPAct) (see Daily GPI, Aug. 9, 2006). Those goals include eliminating fraud, checking anticompetitive behavior, promoting transparency, identifying serious violations, and encouraging compliance. Long term, the hope is that there will be widespread self-regulation among the market players, he said.

FERC’s market oversight role comes from what he called “the first large-scale [gas and power] market manipulation” in the California market in 2000-2001 that had a serious impact on the prices western customers paid for electric power.

That market upheaval involved a number of serious violations by market players, he noted. “And one of the big issue coming out of [the situation] was misreporting of prices to the index publishers and there were various strategies employed to game the market,” Ellsworth said. “In addition, a lot of trading was taking place online that was compromised by Enron,” and there was a lot of insider trading information.

One of the actions taken by FERC was the institution of a new surveillance tool, Form 552, which must be filed each year by anyone trading more than minimal volumes in the market. One thing the form does is identify the number of transactions and volumes that are indexed and those that are done at fixed prices that go into price surveys conducted by publishers such at Natural Gas Intelligence (NGI) that create the indexes. It also require traders to say whether or not they report their transactions to index publishers.

Ellsworth did not seem overly concerned that the latest Form 552 analysis showed that about 72% of transactions prices were set by the indexes rather than negotiated prices. He was concerned, however, that FERC’s survey doesn’t provide the granularity necessary to see what is going on at trading locations which don’t have as much fixed price reporting.

(NGI, and other publishers which follow policy guidelines set out by FERC, report the number of trades and volumes that go into the aggregation of prices at each location.)

Ellsworth said that FERC’s enforcement staff has grown from five people in 2001 to 500, including lawyers, economists, former traders and information technology specialists, currently, spread over several divisions (investigations, market monitoring, surveillance, among others). He added that the federal agency now has a lot more price data than it did back in 2005 when it was given authority to assess penalties of up to a million dollars per violation.

Since 2007, FERC has levied $602 million in civil penalties, and another $300 million in what Ellsworth called “disgorgements” (profits determined to be unjust or ill-gotten). Last year, FERC ordered Barclays Bank plc and four of its traders to pay $453 million in civil penalties and disgorge $34.9 million, plus interest, in unjust profits for manipulating electric power prices in California and other western markets between November 2006 and December 2008 (see Daily GPI, July 17, 2013).

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |