Bakken Shale | E&P | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Montana Starts Temporary Water Leases to Address Oil, Gas Needs

With the advent of increased drilling on Montana’s portion of the Bakken Shale play and more importantly other wildcatting areas of the state, a new state program for temporary leasing of water rights has kicked off, anticipating added demand for water supplies to support hydraulic fracturing (fracking).

Temporary leases are being granted by the Montana Department of Natural Resources (MDNR) under a 2013 state law (HB 37) authorizing the program. MDNR sought the authorization from state lawmakers to address the needs of oil/gas development in the Bakken Shale and elsewhere in the state, according to Colleen Coyle, an analyst writing on the blog of a new website tracking water rights nationally, Watersage (www.watersage.com).

The temporary leasing rights must be applied for by the holder of given water rights on behalf of an end-user, such as an oil/gas exploration/production (E&P) company, and meet various state-mandated requirements, including demonstrating that other water users will not be adversely affected by the proposed appropriation or change in the water rights. An analysis of potential adverse effects also is required.

“In Montana if an oil/gas operator wanted to buy water from a [agriculture] irrigator, and his beneficial use designation was ‘agriculture’, the oil/gas guy would have to go through a change-of-use process that could be a problem, depending on the location and water source involved, ” said David Galt, executive director of the Montana Petroleum Association, which was instrumental in getting HB 37 passed. “Getting a change-of-use could be very, very difficult.”

The temporary “HB 37 expedites the leasing process and puts the onus on an objector to prove that the change would have an adverse impact. As water becomes more of an issue and the people who would not like to see us drilling in Montana make water more and more of an issue, the bill will have long-term benefits to the industry.”

The new law could help in northeast Montana, where increased drilling is expected for Bakken supplies that spill over from neighboring North Dakota, but Galt said it was not the main driver for HB 37. The area where the Bakken comes in has a lot of unappropriated water, he said, so that isn’t prime area for applying the law, but other parts of the state are.

“There is a lot of wildcat, exploratory stuff going on around Montana,” Galt told NGI’s Shale Daily on Monday. “Depending on which river system and drainage and other sorts of things, the water leasing bill can be very important.” The biggest benefits are still a way off in the future, he said.

Coyle said the intent of the law is to make the process relatively short, typically less than four months because “if there are valid objections the lease won’t be granted. She noted that the process for a traditional water rights ownership change takes up to two years or more. Coyle’s firm, Water Sage, provides a web-based mapping platform that integrates water rights data, land ownership, and relative priority that helps users evaluate key elements of water rights.

“The process for temporary water rights is very specific to certain circumstances [such as fracking oil/gas wells],” Coyle said. “The regular [water rights] change authorization process is much longer.” It is at least a couple of years, and she says “a very high burden of proof” is placed on applicants to show the change would not have any adverse effect on other water users.

In Montana, the law attempts to provide what Coyle called a “streamlined process” for these temporary leases for oil/gas and industrial applications, but it puts the limitations of two years time during any consecutive 10-year period on the leases. In addition, the leases cannot involve volumes that exceed 180 acre-feet annually.

“Water use for hydraulic fracturing in the United States is a very small part of the overall water demand, yet access to water is crucial for successful fracking operations,” a Sacramento water rights attorney, Nicholas Jacobs, with Somach Simmons & Dunn, told a fracking seminar last Tuesday in Los Angeles. “Understanding your water rights related to a potential project is crucial to a successful fracking play.”

Each state has its own process for granting water rights and water rights leases. “All of the processes for acquiring water rights, changing water rights, leasing water rights, temporarily leasing water rights are governed by the states,” Coyle said.

Coyle indicated that she was unsure if the Montana approach would wind up being a model for other states. “It is probably too early to tell,” she said, reiterating that the advent of Bakken drilling picking up in eastern Montana was a major driver behind the state legislation being passed.

“Change obligations [related to water rights] vary from state to state and exist as a means of protecting the rights of existing water users,” Coyle said. “That is a common theme in water law and water policy across the West — protecting existing, or ”senior’ water users.”

Last year, when Montana’s temporary leasing law passed the legislature by wide margins, state water officials emphasized that the state’s 1973 Water Use Act includes the process for protecting the rights of all existing water rights owners.

“HB 37 creates a new process, as a very limited exception to the change process, to allow water right holders to be able to temporarily lease their water rights for other purposes,” said Tim Davis, water resources administrator in the Department of Natural Resources. “This new process is faster than the normal change process, but it will also contain specific limits to help ensure that other proprietors will not be adversely affected.”

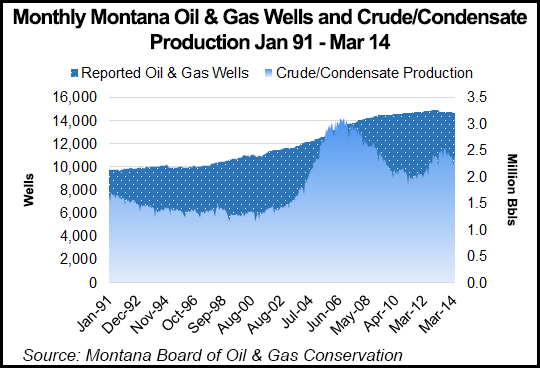

While not a Bakken powerhouse on the same level as North Dakota, Montana has had more than 14,000 oil and gas wells operating since late 2007, according to Montana Board of Oil & Gas Conservation data. Crude and condensate production, which peaked at 3.13 million bbl in 2006, declined for years before a rebound beginning in 2012, and reached 2.44 million bbl in March 2014.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |