Utica Shale | E&P | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Northern Utica Not Yet A Bust; Oil Windows Seen as Key to Revival

Despite poor results and the unabashed early decisions of some unconventional operators to abandon altogether what was once thought to be the core of Ohio’s Utica Shale, neither the oil and gas industry nor the communities waiting for economic opportunity have written off the play’s northern tier.

Even as operators push farther south into West Virginia to replicate the dry gas success of southeast Ohio and as a similar pattern slowly unfolds nearby in southwest Pennsylvania (see Shale Daily, March 26; June 5), optimism for the future of the Utica Shale in the northwestern part of the keystone state has not subsided.

In nearly a dozen interviews with oil and gas professionals, local landowners and community leaders in Ohio and Pennsylvania, and through the analysis of both state production data and the plans of some of the Appalachian Basin’s leading operators, there appears to remain significant enthusiasm about the Utica’s black and volatile oil windows. It’s only a matter of time, sources say, before operators learn how to move those molecules through the small pores of shale rock underneath a five-county region in northeast Ohio and a larger area to the west, while some acreage in northwest Pennsylvania is believed to hold the same potential.

In the last four months alone the Utica’s northern tier in Ohio, which today is generally perceived to consist of Mahoning, Trumbull, Stark and Portage counties, and to a lesser extent Tuscarawas County, received a series of signals that spelled trouble for the oil and gas industry’s future in the region (see Shale Daily, June 3; March 12; March 11)

Among the biggest announcements was BP plc’s $521million impairment. The company said in April that it would market its roughly 100,000 acres in Trumbull County and the surrounding area, saying only that the acreage did not match the needs of the “company’s portfolio” (see Shale Daily, April 29; Nov. 18, 2013)

Around the same time, Halcon Resources Corp., citing poor results and inconclusive data, decided to suspend its drilling program in northeast Ohio and northwest Pennsylvania (see Shale Daily, March 5).

Those events, among others, prompted local news media to question the Utica Shale’s long-term role in what has recently been a regional economic rebound. They set off local discussions and stirred further speculation about what the industry and investors have for some time accepted about the uneconomic results in the northern tier (see Shale Daily, Jan. 2).

“I don’t think any of us familiar with oil and gas in the state of Ohio have written-off areas that have thus far proven disappointing in the north,” said the Ohio Oil and Gas Association’s Executive Vice President Thomas Stewart. “You can’t have a boom if the geology doesn’t exist under current technology, and it’s just not there yet in some of the areas north of Carroll County.”

Thomas acknowledged that there have “been some pretty good wells on the northern end,” but added that they’ve mostly been spotty. Production data filed with the Ohio Department of Natural Resources (ODNR) does show, in rare cases, wells that have turned out notable volumes of oil and gas, but most have grossly underperformed the statewide average of horizontal Utica wells in recent quarters.

Still, Thomas said the play’s early days, when operators secured the bulk of their Utica acreage in the north, and ongoing tests in the northern oil window point to a strong likelihood that the northern tier will ultimately be developed. The tests are being conducted by EV Energy Partners LP (EVEP), Chesapeake Energy Corp. and Total E&P USA Inc.

“People will figure out how to move liquid through very tight low-permeability rock,” he said. “You’re trying to move large chains of molecules through very small pores. The one thing I’ve figured out about this industry is that it’s better at solving problems than any other.”

Much of the disappointment surrounding the northern tier arose with the expectations of Ohio’s oil producing past and the delineation efforts that took place in the state during the Utica’s early years. Stark County, for example, once was home to the East Canton Oil field, one of the best producing fields in state history, while the Mecca field in Trumbull County was equally productive.

More recently, though, financial analysts were forced to swallow what the dominant companies scooping up land in the state had to say about the Utica’s prospects when the formation hit investor radar screens in 2010 and 2011. Many believed the play would be analogous to the Eagle Ford Shale in Texas, with distinct oil, condensate, wet and dry gas windows. Since then, producing oil has proved to be a challenge (see Shale Daily, June 10).

Devon Energy Corp. was an early entrant into the Utica Shale, securing some of its first horizontal permits in 2011 in Ashland and Medina counties where it drilled and plugged dry holes. It continued to permit across a swath of land throughout the next year along the Utica’s western edge, completing unsuccessful wells in Coshocton and Wayne counties in search of black oil. It even drilled as far west as Knox County, which is more than 100 miles west of the play’s current core in the southeast, before abandoning the Utica and selling its acreage (see Shale Daily, Feb. 4, 2013).

“The real information that’s missing on all this with the north and west — what’s really been kept close to the vest — is exactly the kind of scientific detail of what Devon, Halcon and BP have actually found in some of these wells across that project area,” said Calfee, Halter & Griswold’s Don Fischbach, who serves as chairman of the energy and natural resources group at the Cleveland-based law firm. “That area has always been expected to be the oily side of the formation,” he added. “I could envision a scenario where those areas are really money in the bank from the standpoint of future development and future operations, especially when a scientific breakthrough comes along that would allow them to harvest whatever has been found.”

Fischbach, who formerly served as general counsel at Continental Resources Inc., said he believes the oil is in place in the north and west. But just as it was then, he said it remains uneconomic to extract in high volumes, especially given the current limitations of horizontal hydraulic fracturing (fracking) technology.

“I think you’ll see much more activity, and it may not be a single well type evolution,” he said. “It’s not uncommon when reservoirs, and how best to complete in those reservoirs — or cracking the code — takes dozens of wells or more. It’s one of those situations where you just don’t know until you get enough bits on the ground.”

Fischbach cited the Bakken Shale’s early adopters in North Dakota and Montana, who drilled deeper to discover bailout zones with their well logs that indicated the formation’s potential and the technological innovations that allowed them to eventually produce it.

Based on discussions with industry executives and others with knowledge of Devon Energy’s efforts on the western edge of the play, Director of the Natural Gas and Water Resources Institute at Youngstown State University Jeffrey Dick, a geologist, said that assuming the northern tier’s geology is similar to that of the west’s, the Utica is likely too shallow and does not provide enough formation pressure.

“There also doesn’t seem to be enough natural gas entrained in the rock to help move the oil out of it either,” he said.

Dick said a recent petrographic analysis by Weatherford International Ltd., detailing the various states of shale rock across the country, highlights the problems of producing oil from low-permeability shale formations. The problem is perhaps more acute in the northern Utica, he said, given how thin the source rock is and the depth at which it sits.

“It’s going to take some tweaking of the hydraulic fracturing process, some sort of chemical treatment that has yet to be developed in order to loosen that oil up,” he said. “I would think the engineering involved is going to play a big part, too.”

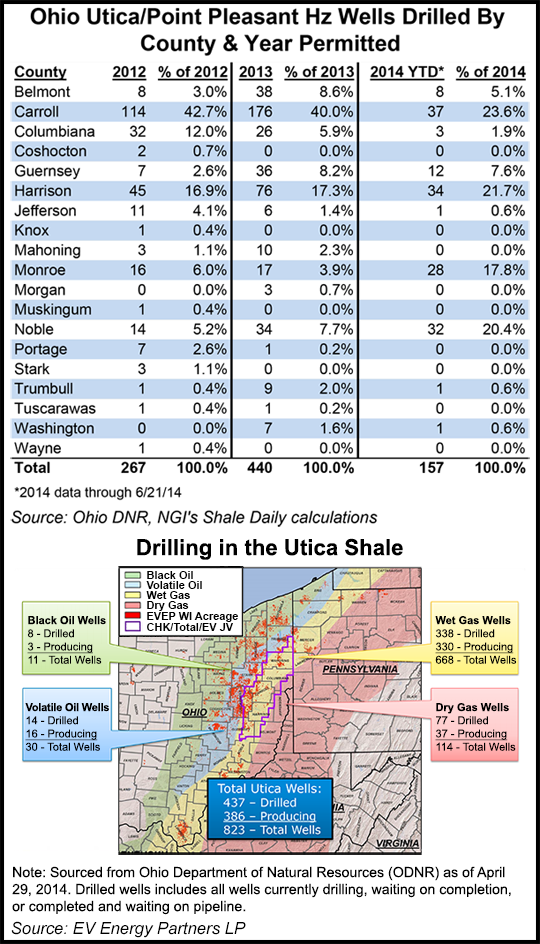

EVEP, through a joint venture (JV) with Chesapeake and Total, has since resumed the quest to test the viability of the Utica’s oil window in Ohio. Of its 173,000 net working interest acres, 81,000 are located within the volatile oil window. The company estimates that there are between 20-30 million bbl of oil in place across 79,000 acres in Stark, Tuscarawas and Guernsey counties. It is also expected to release the first data set from its highly anticipated Parker well in Tuscarawas County later this summer, with results from a couple other wells in the oil window due later this year (see Shale Daily, May 13)

“The challenge in the oil window appears to be fracture design and minimizing reservoir damage upon completion,” CEO Mark Houser told financial analysts during a first quarter conference call earlier this year. “We are working with industry partners on studies designed to help the partnership better understand the flow capacity of the oil window rock.”

As of June, in all of the Utica, only 11 black oil wells have been drilled. Those are primarily located in northern Ohio, while another 30 volatile oil wells have been drilled further south near Guernsey and Tuscarawas counties by different operators, according to EVEP.

Company spokesman Ron Whitmore declined to discuss specifics about the tests, citing proprietary concerns and saying it was still “premature” to draw any conclusions about them.

According to ODNR data, Chesapeake Energy’s Gribi well, completed in 2011 in Tuscarawas County, produced 7,639 bbl of oil and 31.2 MMcf of natural gas in 2012. During 3Q2013, that well, one of just two producing in the county, produced 1,176 bbl of oil and 15.7 MMcf of natural gas. Others completed more recently by the JV in nearby Stark County performed in a similar fashion, trending below the 3Q2013 state average of 5,439 bbl oil and 137.17 MMcf of natural gas (see Shale Daily, April 25; Dec. 31, 2013).

One anomaly in the Utica’s northern tier, however, was Halcon’s Kibler 1H in Trumbull County. That well tested at a rate of 2,233 boe last year, with liquids accounting for 75% of production. The well, which impressed analysts at the time, also tested at 860 barrels of condensate per day and 4.5 MMcf of natural gas (see Shale Daily, Aug. 5, 2013).

“I don’t put a lot of stock in what publicly traded companies put out in initial production reports, but if you look at what Halcon released at the Kibler, that well looked really good and there was a fair amount of excitement about it,” Dick said. “Then a half year later, they’re backing away from the northern Utica. It’s quite possible that some of these media reports and talk about what’s gone on up here are exaggerated, but you know how these companies work, they move capital and head to where the best results are and come back to these other areas later.”

Halcon didn’t have the same luck at its other five producing wells in Mahoning and Trumbull counties, where some production reports show no gas at all.

“Since we’re not active in the play I can’t say much,” said Halcon spokeswoman Kelly Weber. “What I can tell you is that we continue to analyze our own well results and results from offset operators. We are in no hurry [in the Utica] since the leases are five years, plus a five year option and much of it is held by production.”

BP fared much worse in Trumbull County. ODNR data shows that its best well, completed last year, was the Buckeye in Hartford Township. That well produced 378 bbl of oil and 20.3 MMcf of natural gas in 3Q2013. The Morrison well, completed shortly afterward, turned up 1,078 bbl of oil in 4Q2013, but far less natural gas. The three other wells that the company completed in the county performed well below the statewide average.

Company officials declined to discuss those wells further, reiterating what BP said publically that the acreage did not meet the needs of the company’s portfolio. BP is “actively marketing” the acreage, with one source close to those efforts telling NGI’s Shale Daily in early June that there have been recent developments in the process. When asked if that meant something positive for BP, the source said “yes and no,” adding that they could not elaborate further.

Trumbull County Commissioner Frank Fuda said BP’s move to leave the area has not created a palpable local sense that the unconventional industry has concluded its work in the area. He said the county has already met with companies interested in BP’s acreage, while much of the commissioner’s current work has focused on midstream projects in the area.

Mark McGrail of the United Shaleowners Association — a loosely knit group of Trumbull County landowners — agreed. But he said patience is wearing thin among those hoping to cash in on royalties.

“We deal with people that have land developed by both Halcon and BP. Those people are disappointed,” he said. “They were excited about the possibility of their oil and gas rights being developed. The impression they received was they thought it was over and done with.

“A lot of landowners, though, don’t understand how some of these companies operate,” McGrail added. “I’ve been talking to these people and trying to explain, saying in other words to just sort of take a pill and calm down a bit; there are companies that will eventually come in and develop the resources.”

Fischbach, of Calfee, Halter & Griswold, said BP still holds the “elephant position” in Ohio’s northern tier, and he added that it’s only a matter of time before the acreage north of Youngstown is turned over and “drilled one way or another.” He said available acreage remains tight throughout the state and that many conventional and unconventional operators are holding their northern acreage with production as they learn more about it and wait for its value to rise with future development.

The same is true in Northwestern Pennsylvania’s Utica Shale, said Dan Brockett, an extension educator at the Marcellus Center for Outreach and Research. A significant amount of vertical drilling is taking place there for oil in shallow formations. A number of larger unconventional independents have a presence in the region as well.

“In Lawrence, Mercer, Crawford and Venango counties, these [unconventional] operators are almost entirely targeting the Utica,” he said. “There are some Marcellus permits here, but that’s still not as economical because it thins out for sure up here.”

Brockett said there are currently two trends in the region. There continues to be an abundance of shallow oil wells in all four counties that make sense to produce at a lower cost than unconventional wells, while both conventional and unconventional operators continue to spud wells and hold acreage by production.

“They can get a whole lot of acreage at a pretty cheap price. What that tells me is these guys are holding the acreage to flip it for shale oil and gas,” he said. “It takes the stopwatch off the equation, and you can also assume that by selling the acreage to a bigger player, it will command a higher price.”

Brockett added that the northern tier in Ohio and Pennsylvania also remains severely constrained by midstream infrastructure. He suspects that over the next several years operators in the region will not move quickly with development, but rather take time to delineate their acreage, make incremental well additions and wait for a gathering and infrastructure build-out.

Both northeast Ohio and northwest Pennsylvania are served by just one cryogenic processing facility operated by Harvest Pipeline Co. and NiSource Midstream Services LLC, with similar facilities located more than 30 miles to the south. NiSource spokeswoman Sarah Barczyk declined to discuss how that facility’s operations have been impacted with fewer operators in the area, but she said the partnership continues to move forward with “strategic developments” in the north that could be announced as early as July.

Brockett said rumor has been circulating in northwest Pennsylvania about a significant midstream announcement, but said in the meantime that operators in the area and across the state line continue to learn more about the northern Utica with an eye toward the future.

“Operators have learned more in the last two or three years,” he said. “One thing that’s important to recognize is a lot of science work is still to be done. The industry is getting closer to learning how to complete better up here and they’re somewhere close to cracking it.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |