North America Oil Boom ‘Consistently’ Defying Expectations, Says IEA Chief

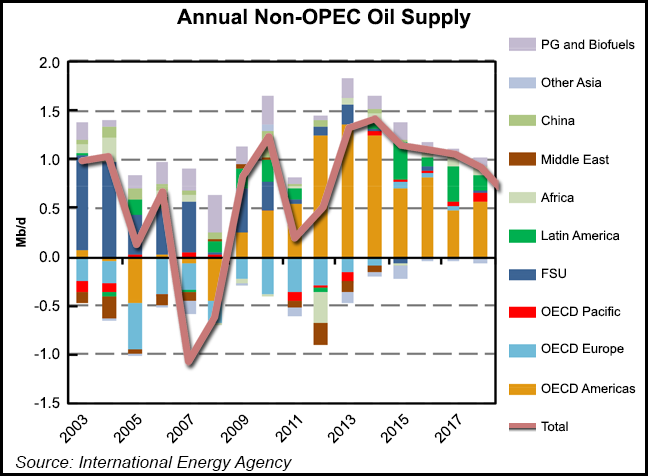

The shale and light tight oil (LTO) supply revolution likely will begin expanding beyond North America before the end of the decade — sooner than expected — as several countries seek to replicate the U.S. success story, the International Energy Agency (IEA) said Tuesday.

The IEA’s Medium-Term Oil Market Report 2014, which offers a forecast for the next five years, comes one week after the global energy watchdog issued an optimistic outlook for North America’s natural gas (see Shale Daily, June 10). The oil report sees global oil demand growth slowing, OPEC capacity growth facing headwinds and increasing regional imbalances in refinery markets.

No single country outside of the United States offers the “unique mix of above- and below-ground attributes that made the shale and LTO boom possible,” but several countries are going to try and replicate it. By 2019, tight oil supply outside the United States could reach 650,000 b/d, including 390,000 b/d from Canada, 100,000 b/d from Russia and 90,000 b/d from Argentina. U.S. LTO output is forecast to roughly double from 2013 levels to 5.0 million b/d by 2019.

“We are continuing to see unprecedented production growth from North America, and the United States in particular,” said IEA Executive Director Maria van der Hoeven in Paris. “By the end of the decade, North America will have the capacity to become a net exporter of oil liquids. At the same time, while OPEC remains a vital supplier to the market, it faces significant headwinds in expanding capacity.”

For almost all OPEC producers, aging fields are an issue, but above-ground issues are escalating, with security concerns a growing issue for producers and investors. As much as 60% of OPEC’s expected growth in capacity by 2019 is set to come from Iraq, where a sectarian war is raging. IEA’s projected addition of 1.28 million b/d to Iraqi production by 2019, “a conservative forecast made before the launch last week of a military campaign by insurgents that subsequently claimed several key cities in northern and central Iraq, faces considerable downside risk.”

The analysis, which offers five-year projections for oil demand, supply, crude trade, refining capacity and product supply, expects global demand to rise by 1.3% a year to 99.1 million b/d by 2019. However, IEA said the market should hit an inflection point, after which demand growth may start to decelerate because of high oil prices, environmental concerns and cheaper fuel alternatives. Once the market hits the inflection point, it may lead to fuel switching away from oil and overall fuel savings.

“In short, while ‘peak demand’ for oil — other than in mature economies — may still be years away, and while there are regional differences, peak oil demand growth for the market as a whole is already in sight,” said IEA.

“It is hard to overstate the degree to which the North American supply boom has, since its onset, consistently defied expectations,” said van der Hoeven.

The baseline of U.S. and Canadian production for 2013 is 330,000 b/d more than IEA had forecast, about 420,000 b/d more than forecast in 2012, 2.2 million b/d higher than anticipated in 2011, and 3.21 million b/d above 2010 projections.

“Understandably, the unlocking of this new resource is often described as having ushered in an era of renewed energy abundance. Yet the easing of oil prices that many had expected in its wake has yet to be felt. Nor has global supply kept up so far with the boom in North American production. In fact, in contrast with North American supply, global oil supply has surprised on the downside.

“Oil markets are in many ways tighter today than they were at the onset of the U.S. shale and tight oil boom, and considerably tighter than they were a year ago. Not surprisingly, far from falling back from their highs under the weight of the new nonconventional supply, oil prices have remained stubbornly elevated.”

The resource potential outside of the United States is said to be considerable, with some estimates indicating that U.S. shale and LTO resources not amounting to more than 15% of the global total.

While no single country may offer the unique combination of above-ground and below-ground attributes that made the U.S. boom possible, “several are nevertheless taking policy steps on the tax and regulatory front to hasten the development of their nonconventional potential, and will benefit from the knowledge base and technological advances gained in the United States,” IEA said.

Less than 10 years ago, the United States was the world’s largest importer of refined products, with 2.5 million b/d of product inflows in 2005, with crude production in decline. Today it has become the world’s largest liquids producer, ahead of Saudi Arabia and Russia, as well as its largest product exporter, with outflows of 2.9 million b/d and net exports of 1.5 million b/d on average in 2013.

“By the end of the decade, North America as a whole will have achieved energy ‘independence’ and have become a net oil exporter with a net crude imports projected at 2.6 million b/d and potential net product exports of around 3.5 million b/d, making it a titan of unprecedented proportions in product markets,” according to IEA.

“That is not to say that U.S. tight oil supply growth will go on forever. Even as U.S. supply reaches this unprecedented level, output growth is expected to slow. Several factors suggest a production plateau may be in sight, including:

Traditionally, the two key drivers of oil demand growth have been economics and population. That may change, according to IEA. In the future, oil growth could be eclipsed by “growing inter-fuel competition,” primarily from natural gas, as well as “efficient technologies and environmental policies.” The cyclical uptrend in oil demand that parallels the underlying economic recovery since the financial crisis and the Great Recession becomes more muted toward the end of the decade.

“From a low point of 610,000 b/d in 2011, oil demand growth reached an estimated 1.1 million b/d in 2012 and 1.2 million b/d in 2013, and is forecast to gain further momentum, averaging 1.3 million b/d in 2014 and 1.4 million b/d in 2015, as global economic growth picks up from 3% in 2013 to 3.8% in 2015.”

Beyond 2015, oil demand is projected to slow gradually, easing back to 1.1 million b/d by 2019, “as growing supplies of natural gas increasingly start taking market share away from oil at the margin, whether supported by economics or environmental policies, and efficiency targets quell demand growth.”

The demand headwinds will be stronger in some markets than others.

“In the United States, oil savings will be driven by an abundance of shale gas, a relatively low-cost and comparatively clean alternative to oil, compounding the impact of efficiency policies. Tightening fuel efficiency standards for automobiles and changing consumer preferences look set to send U.S. gasoline demand (roughly 10% of the global demand barrel) back on the declining course on which it embarked in 2007, and from which it briefly strayed in 2010 and the second half of 2013.”

Plentiful gas also should displace oil increasingly at the margin in the U.S. transport sector, including rail and road freight, “a prospect that would have seemed unthinkable a few years ago.”

Crude trade should gain momentum through the end of the decade. By 2019, the United States, thanks to a combination of rising production and domestic demand attrition, should become a larger oil exporter than it is today. However, crude imports, mostly from Canada, will remain substantial. Taken in aggregate, North America will have become a net oil exporter, according to IEA forecasts.

“While the world’s appetite for oil continues to grow, international long-haul crude trade is projected to shrink as producers keep more and more of their crude at home and refiners source more and more feedstock locally,” said economists. “The key drivers here are North America and the Middle East. The former has emerged as a powerhouse in merchant refining and is increasingly running its own crude. The latter remains the world’s leading crude exporter over the forecast period but loses market share at the margin, as a result of rapid refining capacity growth aimed at both domestic and foreign markets.

“The net result is that crude markets contract in both volume and geographic reach: less crude is traded internationally, while the main trade routes increasingly converge on Asia from producers in the Middle East, Africa and the former Soviet Union. By the end of the decade, though, westbound trans-Pacific trade also rises, as Asian refiners import growing volumes of feedstock from South America and, at the margin, North America.”

U.S. regulations that have restricted crude and condensate exports have played a key role in shaping the impact of North America supply growth on global markets, IEA said.

“As North American production continues to increase, those regulations have moved up the policy agenda in Washington amid growing (though not unanimous) calls for a regulatory overhaul, fueled by concerns that persistent export restrictions might soon constrain supply, as the capacity of regional refineries to absorb further production growth may not be unlimited.”

IEA analysts assume that the main U.S. regulatory framework governing crude exports will remain in place but provide “sufficient flexibility to allow marginal export growth without undergoing a full-blown reform…

“Suffice it to say that a full lifting of U.S. crude export restrictions would likely lead to an increase in both imports and exports of crude by the United States compared to our forecast. How that would affect net balances remains to be assessed.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |