Alberta Industry Working the PR Side of Fracking

After completing 8,900 horizontal hydraulically fractured wells since the end of 2007, Alberta industry leaders are searching for a community-relations formula that will be as effective as the drilling technology.

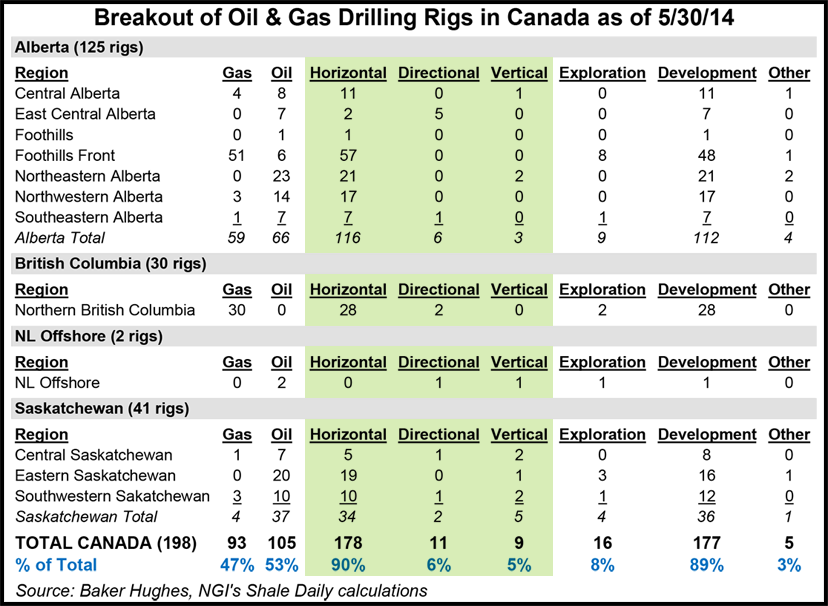

Strategy discussions Thursday among business and government officials included a startling demonstration that fracking — now used by nearly three-quarters of Alberta wells outside the oilsands — no longer flies under the public radar.

A group of property owners paid admission fees to a conference staged by Petroleum Technology Alliance Canada (PTAC), to pepper senior corporate and regulatory officials with questions in the main dining hall of the Calgary Petroleum Club.

The emerging peacekeeping formula takes cues from increasingly annoyed landowners such as Nielle Hawkwood. The rangeland around her family’s generations-old Ironwood Ranches, deep in scenic foothills of the Rocky Mountains, has become studded with 110 wells and more are being drilled at a brisk pace, she said in an interview.

Under traditional regulations, wells are approved one at a time. Only nearby landowners, liable to experience “direct and adverse” effects, are notified and have rights to demand formal reviews and hearings.

Across Alberta and in northern British Columbia (BC), hydraulic fracturing for liquids-rich shale gas and tight oil sets a new pattern, known in the industry as resource plays. Companies buy up large spreads of drilling rights and exploit them with repeatable wells described as more like factory assembly lines than traditional resource exploration.

“We get suspicious if there’s no disclosure,” Hawkwood said, in calling for better notice of all aspects of the programs such as their total planned areas, well numbers, contents of the fracking fluids, risks of spills and waste management programs.

“The rural grapevine is high and wide.” Out on the Alberta range, residents from longtime ranching families to a growing population of ex-urbanites believes they are seeing deterioration of water, air, livestock health and wildlife populations.

Bob Willard, a senior policy adviser with the Alberta Energy Regulator (AER, formerly the Energy Resources Conservation Board or ERCB), told engineers, earth scientists and corporate executives to take such warnings seriously if they want to keep their ability to operate briskly in Canada’s chief gas- and oil-producing jurisdiction.

“We have to appreciate the community,” Willard said. Appreciation, he explained, means accepting that negative or skeptical perceptions of industry — right or wrong, or easily disproved at scientific or technical level — are a reality that affects activity application and approval processes.

The industry needs to see the big community relations, environmental and political picture, Willard said. Companies can no longer afford old habits: “Landmen hiding behind minimum requirements [for public notice] of the regulator is part of the problem.”

The AER is gradually replacing old minimal requirements rooted in the bygone gas and oil exploration era with a new regime known as play-based regulation.

The emerging regulations strongly encourage or require early disclosure of exploitation plans for large shale or tight geological formations, up to the scale of regional drilling plays. The AER has twin goals of maintaining straightforward, efficient regulatory proceedings for industry and keeping the peace in Alberta communities.

Disclosure of industry practices in projects as they proceed from their cradles to their graves is also an element of the new regime, made possible by widened authority over environmental approvals and policing under a regulatory overhaul that created the enlarged AER from the ERCB last year.

Initial mandatory performance monitoring of horizontal hydraulic fracturing wells is generating detailed public reports on industry behavior concentrated on water use, liquids storage, and fluid waste management, said AER environmental data specialist Michael Bevan.

Full data on use of chemicals including fracking fluid recipes is being collected, and a public reporting system is expected to follow when the records can be verified as clear and accurate, eliminating frequent murky spots such as variable spellings or brand names for materials.

Less formal improvements are also spreading across Alberta’s often professionally reserved industry and regulatory officer class, with help from veterans of the oil and gas sector in the United States.

Community picnics work, said Susan Stuver, a researcher from the Texas A&M University Institute of Renewable Natural Resources.

Friendly barbecues with landowners work wonders at spreading proper perspective on the industry that otherwise only appears, for instance, in annual 200-page reports by the Texas Water Development Board that nobody reads, said Stuver. She urged industry to respond to criticisms posted in online internet forums by increasing direct, personal contacts in communities where it works: “The people driving the social media train are not going to change,” she said.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |