E&P | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Not So Fast in Miss Lime/Woodford Stacks, but Pilots Holding Promise

The Mississippian Lime (ML) formation hasn’t proven itself to be a go-to drilling spot yet, but pilot wells show promise where the rocks, clay and sand intersect in Kansas and Oklahoma.

The stacked formations are so varied and the pilots are still so new that determining whether there’s enough oil and liquids for the taking remains elusive. It likely will take two years before there’s a move to true manufacturing. A Wood Mackenzie upstream analyst said it’s still wait-and-see. Producers are taking it slow, but they also see a lot of promise.

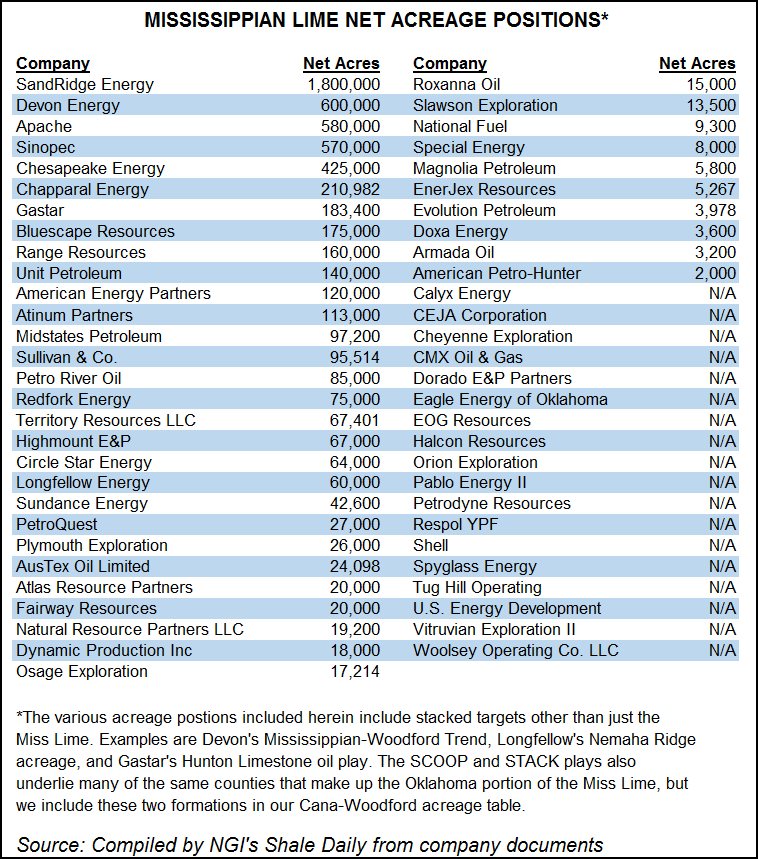

For its part, Oklahoma City-based private Longfellow Energy LP has placed its chips on its Nemaha Project, a stacked oil play in Oklahoma’s Garfield and Kingfisher counties. Also rolling the dice in ML/Woodford stack include Devon Energy Corp., Newfield Exploration Co., Continental Resources Inc., SandRidge Energy Inc., Gastar Inc. and a lot of upstarts, including an affiliate of Aubrey McClendon.

It’s still wide open on what to expect once the pilots are completed, Longfellow President Todd Dutton told NGI’s Shale Daily. The Midcontinent formations are spread within the Central Kansas Uplift and the Nemaha Ridge, which runs between the Sedgwick and Cherokee basins in Kansas. To the south of the Los Animas Arch is the gassy Hugoton Embayment, which is north of the Oklahoma border and the prolific Anadarko Basin. Those stacks of formations are requiring science and patience, and upfront investments.

Newfield, which calls its holdings in the Midcontinent play the Stack, is in north-central Oklahoma, also in Garfield and Kingfisher counties. Continental coined the term SCOOP for its South Central Oklahoma Oil Province within the Anadarko Basin (see Shale Daily, Oct. 11, 2012). Gastar refers to its acreage as the Hunton play. McClendon’s American Energy Partners LP has dubbed it CNOW (see Shale Daily, Feb. 24a).

By whatever name, Stack, SCOOP, CNOW or simply ML/Woodford, it’s a different kind of reservoir stack than any other.

The ML is one thing. The Woodford is another. In between, “we’ve got a different reservoir, a different rock dynamic,” said Dutton. The Kansas border is where the whispers about the oil-rich content first were heard. “And those are the counties that were getting a lot of activity. Those also are the counties where it’s turning out that it’s noncommercial, really…”

The U.S. arm of Royal Dutch Shell plc was unimpressed enough to put on the market about 600,000 net acres and 45 producing wells in the ML (see Shale Daily, Sept. 25, 2013).

That doesn’t mean that activity alone in the ML hasn’t continued. Kansas oil production recently hit 134,000 b/d, the highest level in two decades (see Shale Daily, April 8). SandRidge, for instance, has almost one million acres in the play, and it can’t sit idly by because of a joint venture with Repsol YPF SA (see Shale Daily, Dec. 27, 2011). A big focus in 2013 was on Sumner County, KS (see Shale Daily, March 3).

But for every “good” well that’s been drilled into the ML, there were 10 “bad ones,” according to Dutton.

Wood Mackenzie upstream analyst Samir Sharma agreed that there’s been more flops than not in the ML. He told NGI’s Shale Daily that “results haven’t matched expectations.” However, “because of the stacked nature of the Anadarko Basin, it meets up with the Cherokee Shelf and producers are trying to tap into those pay zones. Underlying the Woodford is high-quality shale.”

The stacked formation is drawing a lot of hoopla, but it’s not going to pay out anytime soon (see Shale Daily, Feb. 24b).

Cashing in Requires Finesse

“The stack play is not in a high water cut, like the Mississippi Lime,” Dutton said. “In large respects, the Mississippi is…really more of a conventional reservoir, getting areas where there is a high oil saturation…” In the stacks, producers can use unconventional drilling to their advantage by drilling down and across, fracturing through the many layers.

The stacked play is varied throughout. Producers can’t necessarily produce through a lateral in the Woodford or between the ML and the Woodford, said Dutton. It requires more finesse. Where ML is stacked with the Woodford, production can flow through one unit, he explained. “You get to produce out of one flow unit, or at least they are related to each other, because they sit right on top of each other…”

Like many ML/Woodford prospectors, Longfellow is cutting into several places across the Nemaha Project to test the different formations. “The stacks are good targets. It’s not more expensive to develop, but yes, you have to drill more wells in the stacked formation…” Longfellow’s wells cost about $4 million for lateral about 4,500-5,000 feet.

Operators now are working to hold leases by production but once results are more transparent, “that’s when we go to manufacturing stage and make money. You drill laterals as close as you can to do it. One in the Woodford, the next in the Mississippi, then move over…” It takes up to 25 days to complete one well.

Longfellow has found the stack to be a mix, some areas 55% weighted to oil, 45% to gas, another piece 60-40. “It starts off a little more oily, and over time, it’s more gassy,” Dutton said.

At the same time the pilots are being drilled, Longfellow and others are building infrastructure. Longfellow has built almost 50 miles of saltwater pipelines and plans to build an additional 20 miles of pipes this year.

Advance Work on Infrastructure

“It’s prudent” to get all of the infrastructure in place before the true manufacturing begins. “It’s kind of like jumping off a cliff,” said Dutton. “You can’t turn around easily and you’ve got to know what you’re doing.” Longfellow is looking toward 2016 as the year when the manufacturing stages begin.

“Once the infrastructure is in, it will be hard for anyone to compete with you,” Dutton said. All eyes are on Devon, which has more muscle than any of the operators and a good knowledge of the onshore formations. “Devon is the big dog in our area,” he said. What the super independent discovers may blaze a trail for others.

Devon, with more than 600,000 net acres across the ML/Woodford play overall, struck multiple oil-bearing intervals that in December were pumping out 16,000 boe/d net, a 47% increase from September (see Shale Daily, Feb. 19). More delineation is to come this year, with eight rigs in operation and plans to drill 200-plus wells.

“All unconventional plays are so capital intensive, if we went to a manufacturing phase now, we’d have to staff up, and I’m not sure we will get to that for a long time,” Dutton said. “Over the last few years until very recently, production data available to the public in Oklahoma was the poorest of any producing state. It’s hard to tell what was really going on. It still kind of is. It’s getting better, and we’re starting to see who’s doing well…”

What happens with most oily plays like the ML, Sharma said, is that the size of the wells are smaller because they lose the natural gas-drive mechanism. “More oil, smaller wells. Obviously, it’s not as profitable. Hence, we talk about the ML and Woodford. It’s a hot name right now, but I’m not sure sure how that will work out.”

The Woodford becomes fairly thin as it extends north and northeast. Devon has shifted its focus in that direction and “that’s probably a good move,” said Sharma. “With better results, better resources, you can read between the lines.”

High Oil Content

Newfield’s Stack is concentrated in Oklahoma’s Canadian and Kingfisher counties, which overlaps initially with the Cana formation, he said. “The wells are expensive but they have huge oil content, 70-80% oil, which is pretty significant.”

Sharma said he lamented the lack of public data for wells with 90 days of production. “It’s difficult to say how much the wells decline or how much they produce…By no means” is the stacked formation ready for a development mode. There still needs to be a “better sense of the subsurface, the cores, etc.” While some operators have been marketing their acreage in the ML/Woodford as “shale,” it’s not actually what they’re drilling.

“Trust me, it’s confusing. We have very little data to go by,” Sharma said. “Right now, we are seeing performance from the SCOOP and we think it could be similar to the stack play, but frankly, it’s early days in Woodford. That said, it’s certainly brought a lot more excitement to the region.”

The stack is “just a difficult play to drill. It’s not simply because of the water,” which can be brackish, “but because of the carbonate benches that are developed. They don’t flow very well, even though it has a pretty good porosity.”

To date well results have been spotty. “Repeatability is difficult to achieve,” Sharma said. “Some companies are basically making the play work with a huge focus on costs and upfront infrastructure investments…”

It will take a couple of years to determine the value of the stacked formations.

“When we get a few more operators moving in and we get a sense” of what operators are finding and what the production history shows from wells drilled this year and late last year.

The two years of history would be needed “before we can actually say, ‘look, there’s really potential here with the stack…” There’s no land grab in sight, however, mostly because a lot of the acreage already is held by production because it overlaps the Cana formation.

The bigger explorers, including Devon and Continental are the producers to watch, and whether they “move up from ‘school’ and try drilling in the stack. Companies that have better oil quality resource plays in their resource portfolio will stick with other plays, like the Bakken, Permian and Eagle Ford” than continue to pour funds into a still unresolved reservoir stack.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |