Shale Daily | E&P | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Best Water-Use Methods for Unconventional Wells Hit and Miss

Operators may argue that unconventional drilling using hydraulic fracturing (fracking) doesn’t require a lot of the overall water used in the United States. But to paraphrase former Speaker of the House Tip O’Neill: all water is local.

That’s the consensus of an analysis about North American drilling and water use by analysts at Societe Generale (SG), who earlier this month published “U.S. Shale and Water Risk: between a rock and a hard place.”

Research collaborators Niamh Whooley, Carole Crozat and Rohit Malpani evaluated 26 North American-based onshore exploration and production (E&P) companies under SG’s coverage, including large independents such as Anadarko Petroleum Corp., Apache Corp., ConocoPhillips, Devon Energy Corp., Encana Corp. and EOG Resources Inc.

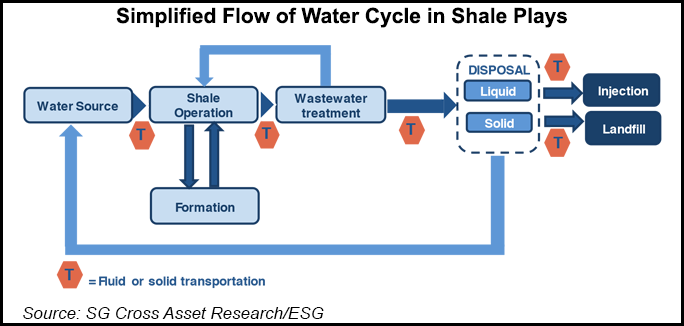

For the majority of E&Ps developing North American gas and oil in shale and tight sands, water is a necessity in the fracking process. In remote areas with little or no water infrastructure, the lack of water has become a real problem.

According to SG, a typical unconventional natural gas or oil well requires about 5 million gallons of water to drill and frack, depending on the geology. Assuming 5,000 new wells are drilled every year, water demand could require almost 25 billion gallons, which comes out at less than 0.02% of total water use in the United States.

“However, water is a local issue, and seasonal and regional variations are causing economic and environmental stress,” the analysts said. “For example, in California (Monterey), North Dakota’s Bakken play and in Colorado’s Denver-Julesburg Basin (Niobrara) most of the hydraulic wells are concentrated in three or fewer counties,” which means more water is drawn in smaller areas.

“The drive to increase efficiencies is high as industry demand for water grows with the development of more wells…Management of water at every stage of drilling and completion is an increasingly core risk management issue for a company.”

Nearly half of the wells fracked since 2011 were in areas with “high or extremely high” water stress; more than 55% were in areas experiencing drought, said the analysts. Extremely high water stress is defined as 80% of available surface and groundwater already allocated for municipal, industrial and agricultural uses.

However, there’s still a lack of reliable, publicly available water-use and management data in many areas of the country, which has hindered industry efforts to develop “appropriately flexible and adaptive best management practices. Timing and location of withdrawal is poorly understood, particularly as water needs in fracturing spike at early stages of development.”

That hasn’t stopped some of the biggest E&Ps from going it alone, using non-potable water sources whenever possible. Analysts said that choice has to become the “default management choice for shale development.” Water for fracking could be sourced from surface water, groundwater (fresh and saline/brackish), and wastewater or through recycling.

Analysts dug deeper into individual E&P company practices to learn about best management practices now in place. What they found was “little evidence of group-level, formalized water policies and management systems.” Overall, there’s been “poor industry performance on water disclosure.”

The best example of water accounting found was by Occidental Petroleum Corp. (Oxy), now headquartered in California, where regulations often are stricter than in other parts of the country. In addition to providing water withdrawals that are broken out by water sources (freshwater, municipal, non-freshwater), Oxy details produced water recycling data and produced water management.

Chemical disclosures on the voluntary FracFocus website also have progressed, according to researchers. In that category, Apache scored tops on toxicity reduction in North American operations.

More regulations by local and state regulators also are in the offing, and E&Ps should consider preparing for them now. Today, mandates for baseline water testing pre- and post-drilling are required only in Wyoming and Colorado. Pennsylvania doesn’t require testing, but “the relevant resumption of liability for pollution of nearby water sources applies,” analysts said.

It all goes back to the county and municipal levels. The reason many unconventional developments are in only a handful of counties is because water use for fracking in those areas may not exceed annual water use by local residents.

Where an E&P drills also determines the water risks. In the massive Permian Basin of West Texas, more than 9,300 wells have been developed since the beginning of 2011. Because operators are going after oil-rich output, however, average water use per well is low when compared to gas-dominated plays that may require 1.1 million gallons per well.

For that reason, the Permian “will likely support a higher density of wells per acre than any other shale play.”

The Permian and the Eagle Ford Shale continue to capture a lot of capital even though Texas is in a historic drought condition, with little surface water and ground aquifers drying up. The Ogallala, or High Plains, Aquifer overlaps the Permian and has experienced some of the steepest water level declines in the country.

Producers have turned successfully to alternatives,such as recycled water or brackish groundwater, of which Texas has plenty. “Vast reserves of brackish groundwater” today are providing about 20% of the water used in the Permian and Eagle Ford, according to the study.

Still, it’s an expensive and energy-intensive undertaking to make slightly salty water usable for drilling. And it hasn’t been determined yet if withdrawing brackish water compromises fresh aquifers.

“For companies operating in these high risk areas, no single technology, whether recycling, brackish water use or greater use of waterless fracturing technology, will be enough,” the SG analysts said. Operators will need to deploy a variety of tools and strategies — and substantially improve operational practices…Measures to improve water efficiency across the shale development water cycle should be a priority for companies in these regions.”

In comparing water recycling rates by basin/shale play, SG researchers found that the Permian tops all others, with 36.6% of its total well count using recycling in the first half of 2013. The Permian was followed by the Eagle Ford (17.2%), Marcellus (7.6%), Barnett (6.8%) and Haynesville (1.8%).

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |