Regulatory | Infrastructure | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

INGAA Says ‘Significantly Higher’ Investment Needed for NatGas Infrastructure

Investment in natural gas infrastructure over the next two decades “will need to be significantly higher” than previously estimated, according to an Interstate Natural Gas Association of America (INGAA) Foundation assessment due out later this month, INGAA CEO Don Santa said.

In its previous study, released in 2011, INGAA found that the United States and Canada would require an annual average natural gas midstream infrastructure investment of $8.2 billion, or $205.2 billion overall (in 2010 dollars), over the nearly 25-year period from 2011 to 2035 to accommodate new supplies, particularly from shale plays, as well as growing demand for gas in the power generation sector (see Daily GPI, June 29, 2011). While he didn’t release specific dollar amounts during testimony before a House Committee on Energy and Commerce subcommittee hearing in Washington, DC, Thursday, Santa made it clear that INGAA believes the industry and regulators will need to do more than previously estimated.

“Spending for natural gas transmission lines must remain strong in order to keep pace with the need to link new supplies to markets,” Santa said. “The assessment, however, projects a greater need for shorter, regional pipelines that connect supply to the existing infrastructure, rather than lots of new, long-distance pipelines. For example, there will be significant demand for systems to carry new natural gas supplies from Pennsylvania and West Virginia to nearby markets such as New York and New England. There will also be demand for pipeline capacity to export such production to other regions. In many cases, this will involve redirecting the flow on pipelines that formerly delivered natural gas to such markets.”

Estimates for petroleum and natural gas liquids infrastructure are also up significantly in the INGAA assessment of U.S. and Canadian midstream infrastructure requirements, Santa said. The report is due out March 17.

The call for greater investment in pipelines is due in part to the inclusion in the most recent assessment of some types of infrastructure not considered in INGAA’s previous studies, but the main driver won’t come as a surprise to anyone who has had their eye on the U.S. energy industry the past few years.

“What we have noted compared to when we did the report back in 2011 is the shale revolution, and the fact that it is of a greater magnitude than we appreciated then, not only with respect to natural gas, but also gas liquids and oil production, and that is driving the need for more pipeline infrastructure,” Santa told the subcommittee.

The House in November passed by a wide margin legislation (HR 1900) that establishes a set deadline for federal and state agencies to approve pipeline applications (see Daily GPI, Nov. 21, 2013). The bill (HR 1900), which was sponsored by Rep. Mike Pompeo (R-KS), would establish a 12-month deadline for FERC to approve gas pipeline applications, and other federal permitting agencies would have 90 days (with a potential extension of 30 days) to complete a separate review (see Daily GPI, May 13). INGAA supports the bill, which has yet to be taken up by the Senate.

While the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission approves pipeline certificates in a year or less, other required permits from a variety of federal and state agencies add to the timeline, and that is where “real discipline and accountability are needed,” Santa said Thursday.

“INGAA’s analysis demonstrates that these agency permits, and not the FERC certificate process, are being delayed for longer periods than in years past. This is not a positive trend, and it is precisely why HR 1900 is needed…if you want to take full advantage of new natural gas supplies by constructing the pipeline network that will be needed to keep pace with dynamic shifts in supply and demand, enacting HR 1900 is one of the few areas where congress can make a measurable improvement.”

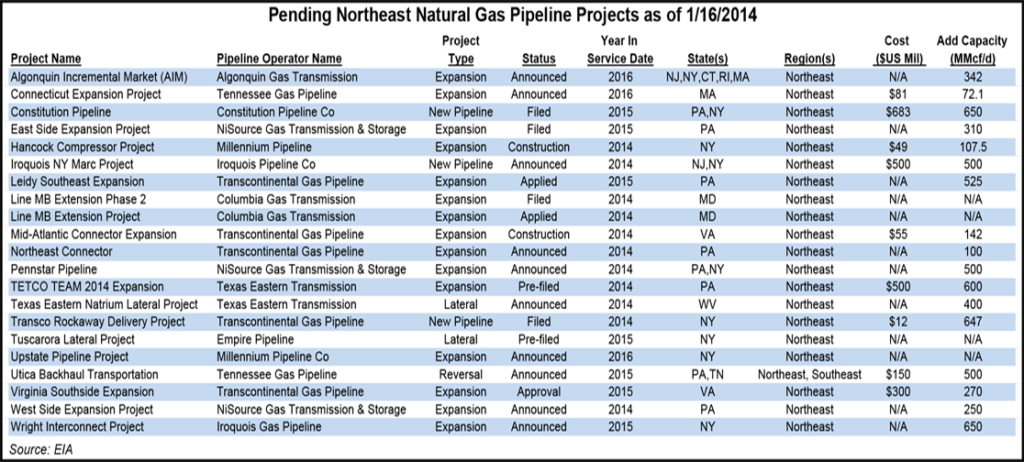

There were 21 pending Northeast natural gas pipeline projects as of Jan. 16, according to the Energy Information Administration. If all of those projects are approved and built, they would add at least 6.57 Bcf/d of capacity.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |