NGI Archives | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Speakers Call for Oil, Gas Industry to Step Up Dialogue With Opposition

At a closed-door meeting in Pittsburgh in 2011, a small group of exploration and production company executives, environmentalists and philanthropists sat down to discuss the polarization that was building around the country’s nascent boom in unconventional oil and gas production.

One of the men in the room, Andrew Place, corporate director of energy and environmental policy at EQT Corp., could sense the tension. A dividing line on the contentious issues that had come to characterize the pace of the industry’s development was immediately clear, and even more evident was where the groups stood on those issues.

“As I sat down, I looked to my left and right and realized that all the operators were on one side of the table and all the non-governmental organizations (NGOs) were on the other. We should have had a seating chart,” Place said. “It takes time to build relationships across this sort of spectrum. We sat there figuratively for weeks and stared at each other, putting our hard lines on the table and no one budged, no one blinked.”

Place said that social divide still needs to be addressed. The industry itself has an obligation to “go above and beyond the regulatory floor” to cover the “real” and “perceived” risks of its operations.

Place delivered his remarks about the experience on Friday at an event in Canonsburg, PA — home to a growing number of regional oil and gas giants — during a presentation about the state of regulatory, government and industry efforts to ensure safe development across the blooming Appalachian Basin.

Place was joined by David Spigelmyer, president of the Marcellus Shale Coalition (MSC), and others. They said one of the oil and gas industry’s biggest challenges continues to be how the public perceives its operations and how growing opposition stands in the way of the country realizing the full benefits of an energy renaissance.

Spigelmyer, who in October replaced Kathryn Klaber as president of the MSC (see Shale Daily, Oct. 22, 2013), which has been dealing with public perception since 2008, said the coalition will focus more narrowly under his leadership on communication efforts with everyone it believes “has skin” in the oil and gas game.

“We have developed a dialogue with conservation groups across the Commonwealth, and that’s one area that we’ll likely do more of because that kind of collaboration with those sorts of groups has been fairly rewarding for us,” he said. “We have operators working with these groups as well to make sure we’re reclaiming property and working properly along pipeline and production operations in a responsible fashion.”

Spigelmyer said his organization’s membership produces 96% of all the unconventional natural gas in the state. As the industry continues to pay billions of dollars in taxes, permitting and impact fees, he said it is too important for its benefits to be overlooked in the face of activist opposition. The group plans to step up its lobby in Pennsylvania, open up more dialogue with the communities under development and work more closely with regulators.

“The focus of the MSC right from the outset was heightened communication within the communities in which we operate,” said Spigelmyer as he wrapped up his fifth public speaking engagement of the week. “I think you’ll see more of the MSC out there as we work to continue developing greater dialogue, and you’ll certainly see us be more active in Harrisburg.”

“Like all forms of energy extraction or production, [horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing (fracking)] is not without risk,” said Daniel Clearfield, co-chairman of the energy group at the Pittsburgh-based law firm Eckert and Seamans. “But it can, and is, being conducted safely and reasonably. The question, however, is how do we convince the general public of that? This, according to many observers is one of the key challenges facing the industry today.”

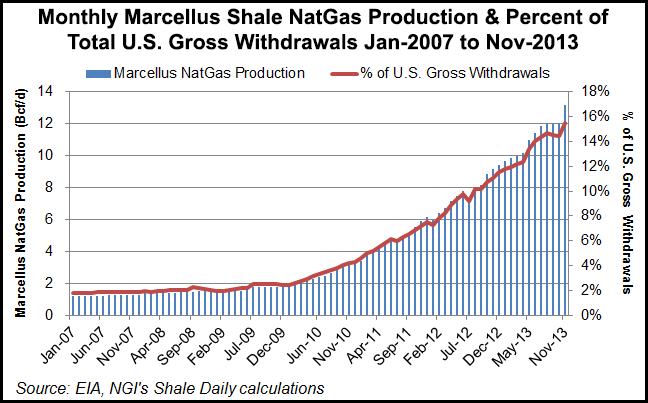

Even if polls continue to show that a majority of Americans support fracking and its benefits, Clearfield said there remains a minority who are opposed. In recent years, Appalachia has seen oil and gas development increase at a rapid rate. In February, the U.S. Energy Information Administration expects operators in the Marcellus Shale to produce 14.2 Bcf/d of natural gas (see Shale Daily, Jan. 14). Combined with the Utica Shale and other formations in the region, the basin will account for 20% of all natural gas production in the country.

But not since the oil booms of the late 20th Century has oil and gas development gotten up close and personal with the more heavily populated states such as Ohio and Pennsylvania, where opposition has continually aligned to thwart industry operations.

The Center for Sustainable Shale Development (CSSD) opened last year with Place as the interim executive director. Friday was his last public appearance in that role as Susan Packard Legros, a lawyer from Philadelphia, has only recently taken over the position (see Shale Daily, March 25, 2013).

Last month the group said it would promote responsible development of the region’s oil and gas by certifying operators that meet 15 performance standards, which go above federal and state regulations (see Shale Daily, Jan. 22).

It remains unclear what kind of impact the CSSD will have on the responsible development of the Appalachian Basin. At the time it was announced, some companies denied an offer to join, while executives of a few environmental groups scoffed and said the effort would fail. Still, He said the CSSD expects to finish its early rounds of operator certification this spring, with officials at the center focused on attracting more companies and participants throughout this year.

“It’s sort of a ”we’ve built it; will they come’ thing,” Place said. “Will other NGOs, foundations and operators see the value in this and engage. That’s what our work will be about in 2014.”

He said some of the CSSD’s standards are similar to the recommended practices of the American Petroleum Institute, the Appalachian Shale Recommended Practices Group and even the MSC. But the value, Place said, does not come in competing with those groups or fulfilling a quota for the number of companies it signs up.

Instead, Place said, working to reinforce a broader message that the industry is working to address public concern is more important.

“It’s hard to measure how you change that discourse out there, but I think it’s very clear given the people who have come into the room that this work of being collaborative and finding a reasonable place in the middle is of the utmost value,” he said. “There are a whole suite of engagements that we as an industry should participate in. There is no one size fits all, no one single silver bullet that addresses all the concerns we face in the basin.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |