Regulatory | Infrastructure | LNG | NGI All News Access

Alaska Taking Stake in Gasline, LNG Project, Rethinking Gas Tax

The state of Alaska will be an equity partner in a pipeline and natural gas liquefaction project that would at last commercialize the state’s vast stranded natural gas resource, Gov. Sean Parnell said Friday.

Alaska is also ending its agreement with TransCanada Corp. under the Alaska Gasline Inducement Act (AGIA), which was seen as a major achievement of the administration of Parnell’s predecessor, Sarah Palin. Alaska and TransCanada, as well as gas producers, will be project partners under “a more traditional agreement,” Parnell said.

“Ownership or participation allows the state to receive a share in the profits over the entirety of the project,” Parnell said during a speech Friday. “When companies build LNG [liquefied natural gas] projects, they often take profits at all points in the value chain. Gas processors take profit, pipelines take profit, the liquefaction facility takes profit, and ship owners take profit. Without ownership or participation, the state would, in essence, pay for others’ profits that reduce the state’s revenue from taxes and royalties.”

This is the first time in Alaska’s history that the state has a framework in place to build an all-Alaska gasline on its own terms and in the interests of Alaska’s citizens, Parnell said. “We have all the necessary parties to make an Alaska gasline project go: three producers, a pre-eminent pipeline builder, an entity in AGDC [Alaska Gasline Development Corp.] that can carry Alaskans’ interests, and state agencies responsible for the royalties and taxes.”

A heads of agreement is expected to be reached soon for the Alaska LNG project and is anticipated to be signed by ExxonMobil Corp., BP plc, ConocoPhillips, TransCanada, and AGDC. It is also to be signed by the commissioners of the state’s departments of Revenue and Natural Resources. The state legislature will review the agreement, Parnell said.

In the next four months, Parnell said he expects to achieve public review of the project guidance documents, including the signed heads of agreement for the LNG project, as well as passage of authorizing legislation.

In late 2012, the producers and TransCanada outlined their plans for LNG export after the state opted to pursue an LNG option rather than piping Alaskan gas to the Lower 48, where shale plays have saturated the gas market (see Daily GPI, Oct. 5, 2012).

“As a partner in the gasline project, Alaska will control its own destiny,” Parnell said. “Ownership ensures we either pay ourselves for project services, or negotiate and ensure the lowest possible costs. As a partner, Alaskans stand to gain more.”

Parnell said he will also introduce legislation addressing how the state will manage its gas resources by authorizing the Department of Natural Resources to modify certain leases, and enter into shipping agreements to move and sell the state’s natural gas. The legislation will propose moving from a variable net tax to a flat gross tax for North Slope gas; allow certain leases to pay production taxes with gas; and enable the departments of Revenue and Natural Resources to manage the state’s gas revenues.

“While most Alaskans have seen past efforts to develop a large gas project falter for various reasons, this time is different,” Parnell said. “AGDC is our ‘ace in the hole,’ meaning we can still opt for the smaller volume ASAP [as soon as possible] project.”

Last fall, the producers and TransCanada chose a site in the Nikiski area on the Kenai Peninsula as the most likely location for an LNG liquefaction and export facility. They had evaluated more than 20 locations (see Daily GPI, Oct. 8, 2013).

Alaska has been courting LNG buyers in Asian markets while buyers have been on the hunt for supplies in Alaska, Canada and elsewhere (see Daily GPI, Sept. 25, 2013; Sept. 13, 2013). However, Japan and other countries have multiple options for sourcing LNG, and Alaskan interests have felt a sense of urgency to move a project forward or be shut out of the market (see Daily GPI, June 3, 2013).

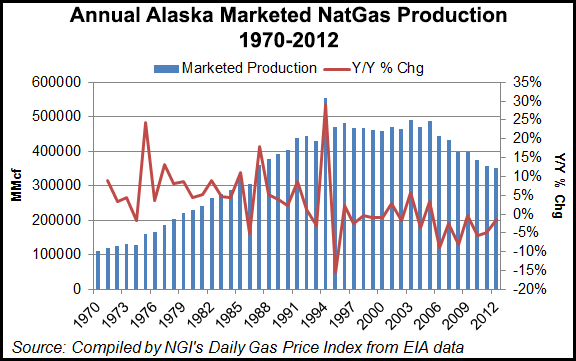

Alaska’s marketed natural gas production, which had increased steadily throughout the 1970s and 1980s, remained relatively stable from 1995 to 2005. But production has declined annually since then, from 487.3 Bcf in 2005 to 351.3 Bcf in 2012, according to Energy Information Administration data.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 |