E&P | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Act 13 Poses Complex Questions for Local Control in Ohio, Other States

With the Pennsylvania Supreme Court’s recent decision that localities can enforce or change zoning laws to contain gas and oil drilling within their boundaries, thousands of townships and municipalities in the state are now enmeshed in a regulatory quagmire that could slow permitting.

While Pennsylvania producers decide to drill or not to drill in the Keystone state, the court’s decision could have an impact on similar battles over local versus state regulatory control that are occurring in other shale states.

The Pennsylvania case tested the constitutional validity of Act 13, a sweeping piece of oil and gas legislation passed in 2012 (see Shale Daily, Feb. 15, 2012), that repealed parts of the existing Pennsylvania Oil and Gas Act and added six new chapters to it. The court struck down a key provision and weakened centralized regulation significantly by returning the right of municipalities to enforce local zoning laws. It remanded other parts of the law to a lower court (see Shale Daily, Dec. 19, 2013).

The ruling, which was immediately challenged by the state administration, has left some thorny issues for Pennsylvania stakeholders to wrestle with. And some are wondering if a new precedent has been set for the country’s nascent oil and gas boom, as legislators and courts in other states wrestle with similar challenges.

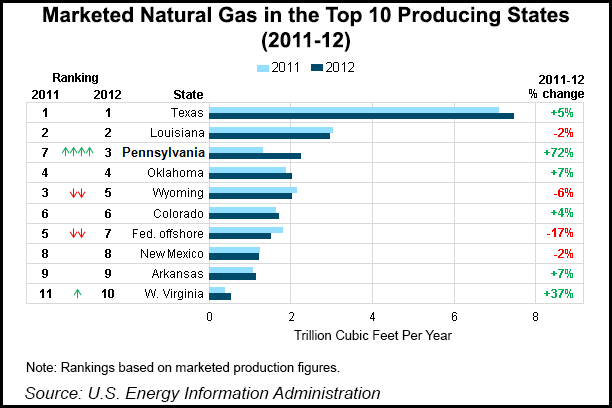

Pennsylvania, the primary home of the Marcellus Shale formation, is at the forefront of the boom, registering as the third-highest producer of natural gas in the country and pushing ever closer to the second highest position, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (see Shale Daily, Dec. 9, 2013). That could mean the high court’s decision will have more clout outside the state going forward.

“If I was a lawyer arguing one of these cases, I would certainly call on this Pennsylvania ruling,” said Michael Krancer, former secretary of the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection, at the time the court ruling was handed down in December. Krancer now practices law in Pennsylvania. “Some state supreme courts are extremely influential, like California and New York, and I believe Pennsylvania will be influential in oil and gas matters considering the level of development that has taken place here.”

Although challenges have cropped up in cities and towns across the country, in places such as Colorado, Texas, California and New York, perhaps for the time being Pennsylvania’s ruling will have the greatest influence in neighboring Ohio, if not for its proximity, then for the timing of a similar state supreme court case set for oral arguments in that state on Feb. 26 (see Shale Daily, Dec. 30, 2013).

Surprisingly, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court’s ruling hinged largely on a reading of Article I, Section 27 in the state’s constitution, a rare environmental rights amendment not found in many other states. It reads in part that “The people have a right to clean air, pure water, and to the preservation of the natural scenic, historic and esthetic values of the environment.”

A plurality of the court found that the centralized zoning regulations violated the amendment, writing that Pennsylvania “has a notable history of what appears retrospectively to have been shortsighted exploitation of its bounteous environment,” and deciding that Act 13 provided a “blanket accommodation of industry and development.”

On Thursday, two state agencies challenged the ruling and asked for it to be reconsidered, mainly because they believe the court’s interpretation did not examine the evidence closely enough (see Shale Daily, Jan. 3), .

Alan Wenger, chairman of the oil and gas law group at Youngstown, OH-based Harrington, Hoppe & Mitchell, who is not involved in the Ohio Supreme Court case but is familiar with its proceedings, said although case law is complex in its interpretations and applications, Pennsylvania’s ruling should not be a significant force in determining the outcome in Ohio.

“That’s not the way these kind of cases work, the arguments of the parties are based on the laws of the state where issues are arising,” Wenger told NGI’s Shale Daily. “The Pennsylvania constitution and the Ohio constitution, I believe, are very different. The basis for Pennsylvania’s ruling, as I read it, is the state is a trustee of public lands and in crafting the legislation that led to Act 13, lawmakers violated that requirement and did not comply with the constitution.”

Ohio’s constitution, like many other states, does not include an environmental rights amendment. Instead, the case before the Ohio Supreme Court deals with Article 3, Section 18, or Ohio’s home rule provision, which extends to municipalities a limited “authority to exercise all powers of local self-government.”

“We don’t have that environmental language in our constitution. Article 3, Section 18 very clearly limits local government as it pertains to general applications of the law,” Wenger said. “The precedent is different here, that section of Ohio’s constitution has been reviewed before in many different contexts, with waste facilities, utilities and radio towers all reaffirmed under state jurisdiction.”

The case in Ohio originated at the trial court level in 2011 in Summit County after the small city of Munroe Falls filed a complaint against conventional driller Beck Energy. In its initial complaint, Munroe Falls alleged that after the company had started to drill on private property there, it failed to file for local drilling permits and did not comply with zoning and right-of-way ordinances.

The case involves a controversial law — House Bill 278 — that almost completely limits local government’s ability to control and restrict oil and gas drilling. It gave the Ohio Department of Natural Resources (ODNR) preemptive authority in the permitting and regulation of oil and gas development. Munroe Falls and opponents of ODNR’s regulatory authority believe the 2004 law directly violates Ohio’s home rule provision.

When the trial court ruled in favor of Munroe Falls, Beck Energy appealed to the 9th District Court of Appeals in Akron, which said in February that the city’s drilling ordinances conflict with state law and overturned the lower court’s ruling (see Shale Daily, Feb. 8, 2013), sending the case on appeal from Munroe Falls to the Ohio Supreme Court, which agreed to hear it in June (see Shale Daily, June 24, 2013).

The case has been watched closely by both sides of the local control debate for more than a year now, with opponents of centralized regulation citing it in their efforts to ban fracking in places across Ohio such as Youngstown, Athens and Bowling Green.

Mansfield and Broadview Heights, both in Ohio as well, have already passed fracking bans and the case is expected to help clear-up local issues about how to enforce those bans when a ruling is finally issued — possibly later this year.

“We welcome the opportunity for the Supreme Court to clarify this once and for all statewide,” said John Keller, lead attorney for Beck Energy in the Munroe Falls case, and a partner at Vorys, Sater, Seymour and Pease LLP in Columbus, OH. “The laws in Pennsylvania and Ohio are very different. We’ll make sure we take a look at the Pennsylvania decision to better understand it and answer any questions that arise from it in our case, but the law here is very clear and constitutional on home rule. It makes no sense to pass regulatory control to those with little expertise in cities and townships across the state.”

Even in Colorado, where five cities have enacted some form of a fracking ban (see Shale Daily, Dec. 4, 2013), with a sixth under consideration, Joe Megyesy, a consultant for the Colorado Oil and Gas Association (COGA) said officials there are keeping a close eye on what the Pennsylvania case could mean for judges who consider bans in Colorado. Although the Colorado Supreme Court has already ruled that state law trumps local law in oil and gas development, activists announced Thursday an effort to put a referendum before voters that would give municipalities greater leeway in approving drilling bans (seeShale Daily, Nov. 6, 2013).

The issue, Megyesy said, is of concern to COGA and it’s watching anything that could potentially affect the direction of the state’s industry.

Wenger said he expects the Ohio Supreme Court to side with the lower court in upholding ODNR’s preemptive authority.

“When you get into precedent, that’s a statutory type of interpretation that considers more broad things like due process or equal protection that cut across political boundaries,” he said. “I expect the high court to look very closely at the home rule wording, the oil and gas statutes and the zoning ordinance of Munroe Falls. They’ll apply the language in those to that sort of balancing test that has helped to develop case law — because that’s how you do it. You don’t say we’re going to do something because another state has done it.”

Thomas Houlihan, of the Akron-based firm Amer Cunningham Co. LPA and the lead attorney for Munroe Falls in the Ohio case, said he hasn’t yet read the Pennsylvania ruling in its entirety, but he added that he will be considering it in his arguments against ODNR’s authority next month. Ultimately, Houlihan said it’s unclear what parts of the law and the case itself the court will factor into its decision.

Wenger said that just as in the Act 13 case, which undermined other parts of the law, (see Shale Daily, Dec. 27, 2013), other Ohio legislation like major overhauls to the state’s oil and gas statutes, including Senate Bills 315 and 165, might get a closer look. Though it’s not likely, they could even be partly affected because they expanded H.B. 278 with new rules for permitting and well spacing, among other things.

“Those could get dragged into this,” Wenger said. “Some of Munroe’s arguments relate to the perceived intention of the legislation passed in 2004, which didn’t consider the scope of oil and gas development in the state. The later laws expanded 278.”

Thomas Stewart, executive vice president of the Ohio Oil and Gas Association, said a similar ruling in Ohio could be devastating for oil and gas development in the Utica Shale. Unlike in Pennsylvania, where the industry has been developing the Marcellus for a longer period of time and where operators have better relationships with rural municipalities, Ohio has a heavier population density.

“The real issue here is urbanization,” Stewart said. “When you get into drilling, it’s very hard to get away from an urbanized environment over here. It’s hard to go anywhere in the state of Ohio where you’re not going to have some kind of residential issues. Township trustees provide a lot of good services, but I’ve never met one who has a clue about regulating a 9,000 foot hole in the ground.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |