Markets | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

U.S. Industrial Growth Clearly Linked to Low Gas Prices, Says IEA

The dawn of the “Golden Era of Gas,” touted two years ago by the International Energy Agency (IEA), has become “more rapid and more pronounced,” but it won’t necessarily create an oil era, according to the 2013 World Energy Outlook (WEO).

“Last year we wrote that North American developments were helping to redraw the global energy map,” said IEA Executive Director Maria van der Hoeven, who unveiled the WEO Tuesday in London. “Indeed, many of the changes we highlighted have only become more rapid and more pronounced since then. Technology and high prices are unlocking new supplies of oil — but of course, also gas — that were previously thought to be out of reach.

“Yet while unconventional production may herald the dawning of a ‘Golden Age of Gas,’ it does not necessarily create an era of oil abundance.” IEA two years ago said the world was entering the “golden age” for gas led by the United States (see Daily GPI, June 7, 2011). IEA is the energy security and forecasting organization for 28 member countries including the United States, Europe, Japan, Canada and Australia.

“At the nexus of supply and demand are energy prices, which remain a live issue in political debate — especially in terms of affecting competitiveness,” van der Hoeven said. High oil prices have been in place since 2011, and “there has also been a substantial widening of the gap between natural gas prices in the United States, Europe and Asia. Electricity price differentials are also large between regions. This is key in our globalized world, where energy costs can be vital to the competitiveness of energy-intensive industries.”

Energy availability and affordability of energy are critical elements of future economic well-being and of industrial competitiveness.

“Natural gas in the United States currently trades at one-third of import prices to Europe and one-fifth of those to Japan,” said IEA Chief Economist Fatih Birol. “Average Japanese or European industrial consumers pay more than twice as much for electricity as their counterparts in the United States, and even China’s industry pays almost double the U.S. level.”

WEO’s economists predict that big variations in energy prices will persist through 2035, affecting company strategies and investment decisions in energy-intensive industries. In WEO’s central scenario to 2035, the difference in regional natural gas and electricity prices narrows somewhat but remains pronounced, while energy price disparities impact industrial competitiveness.

“The United States, which experiences relatively low energy prices, sees a slight increase in its share of global exports of energy-intensive goods, providing the clearest indication of the link between relatively low energy prices and the industrial outlook,” said van der Hoeven. “Conversely, the shares of the European Union and Japan both decline relative to current levels.”

Key to adapting to higher energy prices over the longer term will be efficiency, what IEA calls the “hidden fuel,” and the “first fuel,'” she noted. “Still, two-thirds of the economic potential for energy efficiency is set to remain untapped in 2035 unless market barriers like fossil fuel subsidies can be overcome.”

Unconventional production may provide energy security by meeting growing demand, but “it can also affect relative competitiveness and market development…”

Birol explained how low energy prices will impact global oil and gas growth.

“Lower energy prices in the United States mean that it is well placed to reap an economic advantage, while higher costs for energy-intensive industries in Europe and Japan are set to be a heavy burden,” he said.

As it did for natural gas, technology has increased new oil resources, which will reduce the influence of OPEC countries’ dominance. The U.S. oil and natural gas boom, Canadian oilsands growth and a growing supply of energy resources outside the Middle East are sapping OPEC’s influence in world energy markets, but only for the next 10 years or so, when “the Middle East — the only large source of low-cost oil — takes back its role as a key source of oil supply growth from the mid-2020s.”

However, as OPEC’s influence in oil markets gains strength, U.S. energy security won’t be at risk again, according to the IEA. In fact, the United States soon will become the world’s largest oil producer and increasingly more energy independent.

“Improved energy efficiency and a boom in unconventional oil and gas production help the United States to move steadily toward meeting almost all of its energy needs (in energy equivalent terms) from domestic resources by 2035,” WEO noted. “The United States is the world’s largest oil producer for much of the period to 2035.”

“Major changes are emerging in the energy world in response to shifts in economic growth, efforts at decarbonization and technological breakthroughs,” said van der Hoeven. “We have the tools to deal with such profound market change. Those that anticipate global energy developments successfully can derive an advantage, while those that do not risk taking poor policy and investment decisions.”

Among the options open to policymakers to mitigate the impact of high energy prices, WEO highlights the importance of energy efficiency as two-thirds of the economic potential for energy efficiency should remain untapped in 2035 unless market barriers can be overcome.

“One such barrier is the pervasive nature of fossil-fuel subsidies, which incentivise wasteful consumption at a cost of $544 billion in 2012. Accelerated movement toward a global gas market could also reduce price differentials between regions.” Gas market and pricing reforms in the Asia-Pacific region, as well as liquefied natural gas exports from North America, “can spur a loosening of the current contractual rigidity of internationally traded gas and its indexation to high oil prices.”

Reducing the impact of high energy prices doesn’t mean there should be diminishing efforts to address climate change, said van der Hoeven. Energy-related carbon dioxide emissions are projected to rise by 20% to 2035, leaving the world on track for a long-term average temperature increase of 3.6 degrees Celsius (C), above the internationally agreed upon 2 degree C climate target.

“As the IEA has said many times, greenhouse gas emissions, two-thirds of which come from the energy sector, are still on a dangerous course,” she said. “But that is not the only persistent problem in the energy sector that requires long-term solutions. Access to modern energy — a basic form of energy security — continues to elude almost a fifth of the world’s population. For billions more, any true sense of energy security is undermined by high energy prices…Security, sustainability, and economic prosperity — this is the classic ‘energy trilemma’ that we face.”

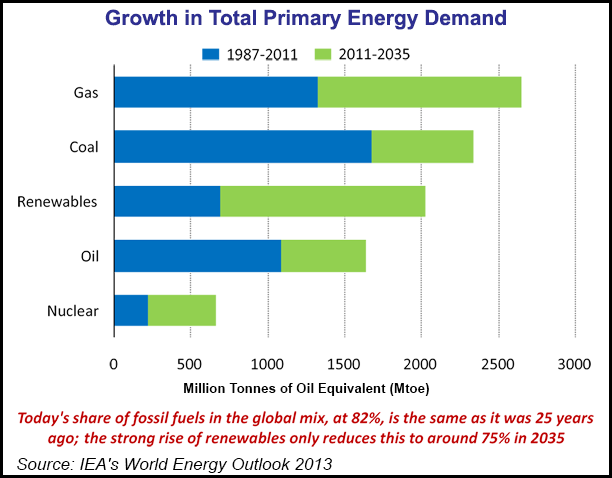

Looking at the growth in total primary energy demand in the past and estimates for the future, the IEA pointed out in its latest WEO that while the growth in gas demand from 1987 through 2011 came in second to the growth of coal, natural gas is projected to take the lead from 2011 through 2035.

The WEO noted that today’s share of fossil fuels in the global mix, at 82%, is the same as it was 25 years ago. Even with the strong rise of renewables in recent years, fossil fuels’ share only declines to around 75% in 2035.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |