NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

NGI Archives | NGI All News Access

Economic, Climate Benefits of Shale Gas Questioned

Unconventional natural gas in the onshore likely will keep U.S. prices low until 2020, but it may not translate to climate benefits or an improved economy, according to an elite group of industry, academic and scientific experts.

The conclusions by Stanford University’s Energy Modeling Forum (EMF), published in September, drew from a compilation of material by leading international energy analysts and decisionmakers from top U.S. government, leading energy producers and providers, universities, and research and consulting organizations. The group met several times beginning in 2011 and formed 14 models regarding the pricing, economic and climate change implications of the shale gas revolution.

Support for the study’s conclusions resulted from different expert teams using separate energy-economy models. The conclusions, some more optimistic than others, form the basis of the 55-pagereport “Changing the Game?: Emissions and Market Implications of New Gas Supplies.”

Financial support was provided by, among others, America’s Natural Gas Alliance, the American Petroleum Institute, BP plc, Chevron Corp., Encana Corp., ExxonMobil Corp., Talisman Energy Inc., Williams, Southern Co., Statoil ASA, TransCanada Corp., as well as the U.S. Department of Energy and the Environmental Protection Agency.

One big question, according to EMF Executive Director Hillard Huntington, is how much will it cost to extract natural gas? More information still needs to be compiled about how much costs will fall as efficiencies increase, as well as how much demand there is going to be and the effect of regulations.

Uncertainties regarding the domestic industry relate to regulation, with federal regulators considering more stringent requirements on unconventional drillers. Also, some states (i.e. New York) and local governments have chosen to ban or place a moratorium on unconventional drilling, causing more uncertainty. Still unknown are the decline rates of unconventional gas wells, which appear to be higher than those for conventional wells. Producers rapidly have moved to multi-pad drilling with multiple extensions, all of which eventually could increase — or decrease — the costs of production.

Prices were a big part of the modeling. The conclusions were varied.

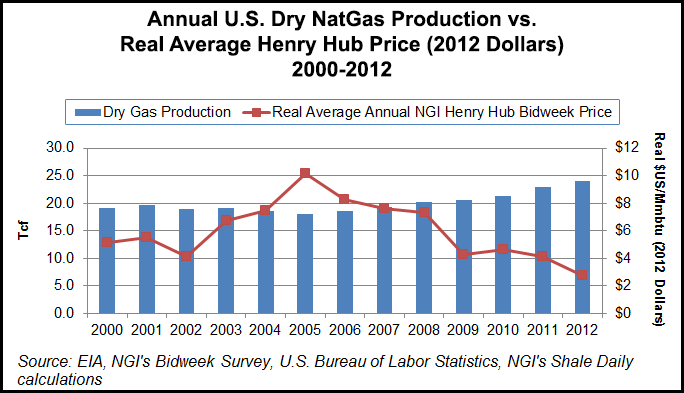

“Natural gas producers currently receive about $4.00/Mcf, up from about $2.50 about a year ago,” the experts said. “Baseline projections in the study anticipate some upward drift in prices that range between $4.03 and $6.24 by 2020 across the models even after adjusting for inflation. More optimistic supply conditions, however, should reduce this price range to $2.67 and $4.95 by lowering production costs.

“The upward drift in prices expected by most groups reflects a market where demand for natural gas slowly catches up to the robust supplies of shale gas that have been recorded since 2006.”

If, for instance, the U.S. economy were to grow faster than anticipated, “natural gas prices will be higher but only modestly so. Prices are no more than 41 cents higher by 2020 in any model if the economy grows by 3.0% annually rather than 2.5%. Additional consumption is not expected to add greatly to the costs of producing more natural gas.” The models assume that gas prices would rise slowly over time as gas demand catches up with excess supply — observations shared by the U.S. Energy Information Administration and other independent energy analysts.<

A lot of industry executives and economists believe that the shale gas revolution will spur economic growth by rejuvenating the chemicals and manufacturing sector. Maybe not, the EMF found.

Shale gas development may inject about $70 billion/year into the economy for several decades. However, while the numbers look big, it’s only about 0.046% of the $15 trillion U.S. economy. Natural gas expenditures today form only about 1% of gross domestic product.

The gas and oil exploration sector, the petrochemical sector and supporting industries would gain, said experts. But it’s difficult to see how those gains might spread to the economy at large.

“Whether this $70 billion spurt alone will create a resurging U.S. economy as claimed sometimes in the public press, appears speculative without further research,” the EMF concluded.

Natural gas also may not be the answer to curbing U.S. greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions after 2020. EMF’s report concluded that yes, power plants are switching to gas from coal. The share of gas in the electricity generation mix has risen to 24% from 16% in 2006. Coal occupies about 41% of the energy mix, down from 52%.

The switch to gas would help to curb carbon dioxide emissions in the short run, said experts. But in the long run, gas may replace nuclear and renewable energy technologies, which have hardly any carbon impact.

The small bump in economic output from shale gas would lead to a corresponding small increase in GHG. “Reinforcing this trend is the greater fuel and power consumption resulting from lower natural gas and electricity prices,” said experts. They concluded that a better way to address GHG emissions would be to adopt a national climate policy, specifically one that includes a price on carbon.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |