NGI Archives | NGI All News Access

U.S. Oil Production Strong as Ever, Says Raymond James

Domestic oil production may be showing signs of slowing down, but analysts with Raymond James & Associates Inc. don’t think it’s a trend.

In a note Monday, J. Marshall Adkins and his colleagues said the most recent numbers point to a slowdown in onshore supply growth “if you squint the right way and ignore the questionable reliance,” but “we believe others are ignoring the longer-term structural change that has happened” in U.S. oil and natural gas fields.

“We think the longer-term trends clearly support our ‘bottom-up, basin-by-basin’ U.S. oil supply model that calls for a continuing rise in output” over several years. “We’ve seen the early signs of that in the last year or so (in fact, actual production has substantially overshadowed our estimates). We don’t believe that a handful of questionable weekly data points is sufficient cause to doubt the longer-term trends of sustainable oil supply growth at these prices.

“Reality says operators are showing no sign of easing back on drilling. More efficient operations and falling cycle times are now enabling producers to chalk up more wells with each rig and more production with each well. That means the U.S. supply juggernaut is still gathering momentum, and we believe it will be some time yet before any sustained slowdown emerges.” That trend is evident in the latest oil production numbers from North Dakota (see related story; Shale Daily, July 16).

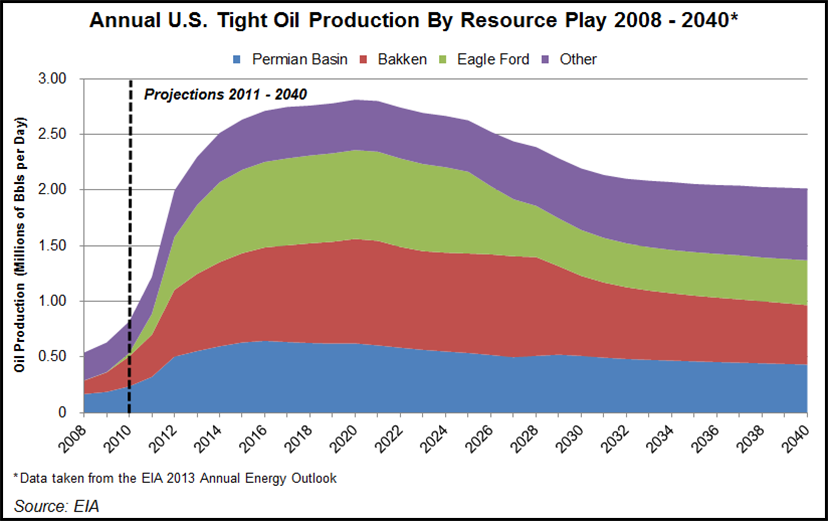

Raymond James analysts in January 2012 said they expected “extraordinary growth” through 2015 in the U.S. oilfields, with supplies reaching 7 million b/d by mid-2013, which was about 1.2 million b/d higher than U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) expectations at the time.

“While the U.S. oil production numbers our models were spitting out seemed crazy at the time, we surprisingly underestimated actual production. We continue to believe that U.S. oil production growth from tight formations is still in its early innings and that there is still a substantial amount of supply growth on the horizon.”

Actual domestic crude output is tracking about 300,000-400,000 b/d above Raymond James estimates. That forecast now is in line with EIA’s Adkins said. He said EIA’s forecast indicates an expected dip in production in 2Q2013 before rebounding to growth again in 3Q2013 as a result of temporarily lower Gulf of Mexico (GOM) production. Some “chatter” has begun because weekly EIA supply data recently pointed to slowing onshore oil output. However, Adkins said it’s too early to view the data as an inflection point because:

Why would U.S. production slow on West Texas Intermediate (WTI) prices above $100/bbl? Some competitor analysts, said Adkins, have pointed “operators moving out to less productive fringe areas of key plays as core areas are drained or rig counts in some areas are declining, combined with rapid decline rates of horizontal wells, or even a rapidly depleting inventory of uncompleted wells.”

U.S. oil supply growth isn’t in jeopardy of rolling over or moving to decline as long as WTI prices stay “anywhere near” where they are today. Canada’s spring breakup and spring storms delayed production schedules in the Rockies and the Bakken Shale this year. However, this would lead to temporary, “usually not permanent,” production disruptions. BP plc, for example, which is the largest single oil producer in the GOM, said in its 1Q2013 earnings report that 2Q2013 oil output probably would decline because of planned seasonal turnaround activity on some higher-margin assets.

“Additionally, production can show up in spurts as the wells are awaiting pipelines, rail or processing facilities to process and transport the crude from the well site,” said Adkins. “Lastly, it is not unusual to see production impacted by general maintenance, which can show up as temporary declines in production.”

The history of the natural gas market should serve as a guide, he said.

“How many times did we see an overzealous sell-sider, itching to be the industry’s hero by calling the bottom in natural gas production, mischaracterize a modest blip in the natural gas production growth trend as a rollover in supply? Recent history would tell us that betting against the industry’s adoption of technology is a losing bet.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |