NGI Archives | NGI All News Access

SandRidge Investor Lawsuit Upheld Concerning Gas Field Misinformation

A federal district judge last Saturday rejected a bid by SandRidge Energy Inc. to dismiss an investor lawsuit that claims the Oklahoma City operator provided misleading information regarding natural gas drilling programs.

SandRidge, the board and its executive team allegedly “provided misleading information on which the plaintiffs relied in deciding to invest” in exploring and drilling oil and natural gas wells, according to the lawsuit, which was filed in 2011 (Patriot Exploration LLC, et al v. SandRidge Energy Inc., et al, No. 3:11cv01234).

The facts presented by the plaintiffs infer that “fraud is cogent and compelling” concerning public statements made by former Chairman and CEO Tom Ward, COO Matthew K. Grubb and Executive Vice President Rodney E. Johnson, who was in charge of reservoir engineering, wrote U.S. District Judge Alvin W. Thompson for the District of Connecticut. However, he dismissed the same allegations against board members Everett R. Dobson, William Gilliland, Daniel Jordan, Roy Oliver and Jeffrey Serota.

The plaintiffs’ case has several facets, but at its center are comments promoting SandRidge’s once prized asset, the Pinon natural gas field in the West Texas Overthrust (WTO), specifically the Warwick Caballos reservoir.

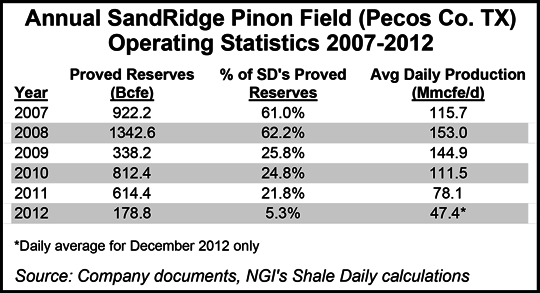

The Pinon Field, which in 2007-2008 comprised more than 60% of SandRidge’s proved oil and gas reserves, is but a small part of the company’s overall portfolio today. Production in the field has declined rapidly, from 153 MMcfe/d in 2008 to just 47 MMcfe/d in December 2012, and the combination of write-offs from lower natural gas prices, lower capital expenditures in the play, and other acreage and company acquisitions left the Pinon Field representing just 5.3% of SandRidge’s total proved reserves at the end of 2012, according to company data.

Ward and the two executives over 2008 and 2009 claimed in investor presentations and in conference calls that the field held some of the company’s best prospects, which drew a lot of investment. Among others, private equity firm U.S. Drilling Capital Management LLC (UDCM) three years ago agreed to invest as much as $75 million (see Daily GPI, June 12, 2009). The plaintiffs said in court documents they had hired UDCM to “identify investment opportunities.” The plaintiffs’ engineering consultant “relied in data provided by SandRidge ‘because SandRidge has done extensive drilling of wells in West Texas and has sole access to large amounts of proprietary data on the Pinon wells.'”

To induce UDCM to make an investment, “SandRidge and its senior officers issued misleading statements and omitted material information that had the effect of overstating the expected returns” from the wells.

Among other things, the lawsuit claims that SandRidge and its senior officers “deliberately concealed the loss of natural gas during the treatment process,” known as “plant shrink,” which is when gas is treated for the removal of carbon dioxide (CO2) and some of the methane is used to run the treatment plant as fuel gas and other methane and heavier hydrocarbons, such as ethane, propane and butane, cannot be separated from the CO2 and is lost. The plaintiffs said they learned the plant shrink “historically experienced by SandRidge results in a reduction in the net amount of sellable methane gas so that just 25% of the total raw gas is sellable.”

For its part, SandRidge had disclosed in each of its annual Securities and Exchange Form 10-K filings since it went public in 2006 that its prospects in the Pinon Field of the WTO “may contain natural gas that is high in CO2 content, which can negatively affect its economics.” While not calculating and showing what the net gas output may be per well per se, each passage has included some indication of how much untreated natural gas must be produced to sell one MMBtu of pipeline quality gas. From its 2012 10-K: “During 2012, the company’s plant shrink has been approximately 5% in the WTO. After giving effect to plant shrink, as many as 3.3 Mcf of high CO2 natural gas must be produced to sell 1 MMBtu of natural gas. The company reports its volumes of natural gas reserves and production net of CO2 volumes that are removed prior to sales.”

However, the statistics that SandRidge has used in this disclosure have changed over the years. While its plant shrink in the WTO averaged 5% in 2012, the company noted in its 2007 through 2011 10-K filings that its historical plant shrink had been anywhere between 6-14%. Moreover, the amount of untreated gas required to produce 1 MMbtu of pipeline quality gas was revealed to be as high as 4 Mcf in those earlier 10-K filings, up from the 3.3 Mcf reported in 2012.

In the “Risk Factors” section of the 2012 10-K filing, SandRidge noted that the reservoirs of many of its prospects in the WTO may contain natural gas that is high in CO2 content.

“The natural gas produced from these reservoirs must be treated for the removal of CO2 prior to marketing,” the company said in its 10-K. “If the company cannot obtain sufficient capacity at treatment facilities for its natural gas with a high CO2 concentration, or if the cost to obtain such capacity significantly increases, the company could be forced to delay production and development or experience increased production costs.”

Because the treatment expenses are incurred on a thousand cubic foot basis, SandRidge disclosed that it would incur a higher effective treating cost per MMBtu of gas sold for gas with a higher CO2 content. As a result, high CO2 gas wells must produce at much higher rates than low CO2 gas wells to be economic, especially in a low natural gas price environment, the company said.

The plaintiffs also claim that SandRidge executives “repeatedly overstated the amount of average reserves of methane gas per well for the wells that the company had historically drilled. Specifically, in numerous presentations and other communications, SandRidge represented that [it] had managed to increase the average reserves of raw gas in its drilled wells to 7.5 Bcfe per well, of which methane gas constituted approximately 3 Bcfe per well. However, this figure of 3 Bcfe failed to take into account the effects of plant shrink. After losses due to plant shrink, the net amount of methane gas for sale was only approximately 1.5 Bcfe, half the amount SandRidge touted.”

To further conceal the negative impact of plant shrink, the lawsuit also alleges that the executive team “repeatedly referred in their presentations and discussions to final sale prices for the methane gas (that is, prices at the pipeline or the point of sale to consumers), explicitly projecting internal rates of return which were based on these final sale prices.

“By repeatedly doing this, SandRidge and its senior officers reinforced the fraudulent perception that all of the natural gas (including the amounts that should have been excluded to reflect plant shrink) was available for sale at the pipeline. In fact, as SandRidge and its senior offices knew, the natural gas could not be sold without first being treated, and the amount of natural gas would inevitably be reduced due to plant shrink during treatment.”

The executives, said the plaintiffs, also “repeatedly understated the expenses associated with methane production from its wells. For example, because the average reserves of sellable methane gas per well was only 1.5 Bcfe (not 3.0 Bcfe) out of the total volume of raw gas of 7.5 Bcfe, SandRidge effectively had to move a greater volume of nonsellable, waste gas through the pipelines (6.0 Bcfe as opposed to 4.5 Bcfe), resulting in a significant increase in the treatment and transportation costs associated with producing sellable methane gas.

“Even more egregiously, SandRidge and its senior officers itemized for plaintiffs 10 different and distinct fees and expenses associated with gas production, but omitted the overriding, most important economic factor — namely, loss of gas due to plant shrink. Thus, when inputting the expected expenses into their own economic models, plaintiffs were misled into believing that the expenses identified by SandRidge constituted the universe of expenses associated with gas production.”

SandRidge’s legal team argued that the “factual allegations in the complaint constitute nothing more than a claim that SandRidge was wrong in its predictions of future profits and outputs, which does not suffice to create a strong inference of fraudulent intent,” said Thompson in his ruling. “The plaintiffs contend that they have alleged facts constituting strong circumstantial evidence that the defendants were, at the very least, reckless in making false and misleading statements. The court agrees with the plaintiffs.”

The judge concluded that the plaintiffs’ allegations “give rise to a strong inference” of deliberately or knowingly (scienter) misleading the public “both by demonstrating motive and opportunity and by providing strong circumstantial evidence of conscious misbehavior or recklessness.”

SandRidge had no comment on whether it would appeal the ruling. Ward, who had founded SandRidge, was ousted by the board last month (see Shale Daily, June 20).

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |