Marcellus | NGI All News Access

Marcellus Holds Great Power, Great Responsibility

Will anyone be able to look back on this time in the United States and not consider it to be a golden age for natural gas? Will anyone doubt that the Marcellus Shale was the blazing star in that firmament?

There’s no doubt that technology has unlocked huge potential from other resources, all starting with the Barnett Shale, but the Marcellus has surpassed its big brother in almost every way. By itself, Marcellus is considered the key reason that domestic gas prices remain stagnant. By itself, the Marcellus should be able to make the Northeast self-sufficient by as soon as the end of 2014.

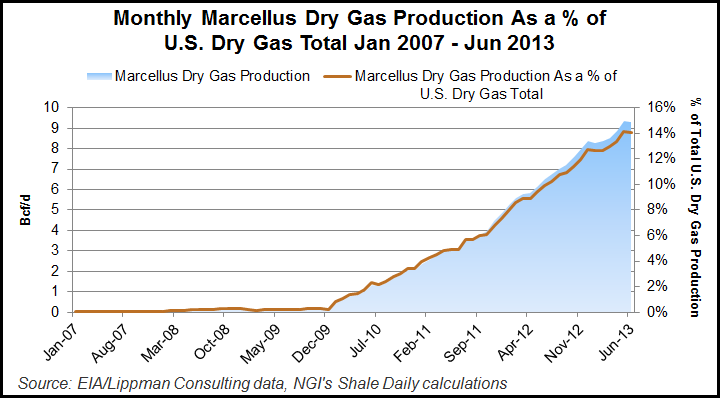

Production in the Marcellus has ramped up at a rapid yet steady pace since early 2010 (see graph). Total dry gas production in the Marcellus (both Pennsylvania and West Virginia) grew from roughly 0.5 Bcf/d in January 2010 to 9.3 Bcf/d in June 2013. The Marcellus represented just 1% of total U.S. dry gas production in January 2010, but has grown to more than 14% as of June 2013.

How big a market force can the play become? How long will it last?

“The Northeast will be long gas and short pipes for much of the next decade,” said Bradley Olsen of Tudor, Pickering, Holt & Co. (TPH). He and colleagues Matt Portillo and Brandon Blossman earlier this month completed exhaustive research on the region, published in “The Last Days of the Northeast Premium.” “The days when high-cost gas pulls from storage, Canada or liquefied natural gas will be fewer each year,” they said.

It’s really hard to put a forward number on production since experience and new technology are increasing individual well output every day.

“The average Marcellus well is going to have a production history that looks to me like it will net somewhere on the order of three times as much gas as the average Barnett [Shale] well, to give an indication of how it’s doing,” Penn State geologist Terry Engelder, who has been on board with the Marcellus from the beginning, said recently (see Shale Daily, Sept. 24a).

Using county-level modeling and acreage delineation in the Marcellus prone area, analysts now believe that based on base rig count assumptions, there’s 30 years of drilling inventory viable at prices under $4.00/Mcf. Yes, explorers will be high-grading their portfolios and developing the low-cost locations first, and wider differentials may pressure the margin, but Marcellus returns “are still strong enough to limit the impact to drilling.”

Pipeline flow reports from Bentek Energy and others indicate that Marcellus output in the first six months rose by 40% or 2.1 Bcf/d year/year compared to the 1.5 Bcf/d of growth in the same period between 2011 and 2012.

“Even as production from other U.S. shale fields has fallen, output from the Marcellus continues to grow,” said Motley Fool’s Arjun Sreekumar. Marcellus output from Pennsylvania and West Virginia is estimated to be up by half from a year ago. “By comparison, output from the Haynesville Shale of Louisiana and Texas has fallen 21%.”

With output today estimated at 9-12 Bcf/d and above, the Marcellus could meet all of the Northeast’s gas demand in the next few years, according to several analysts. Barclay Capital’s Biliana Pehlivanova and Shiyang Wang said the region could become self-sufficient in time for the 2014-2015 heating season. The TPH forecasts are not as optimistic. They extend to 2020, with the Marcellus supplying about 35% of Northeast demand by the end of 2013, rising to about 55% by the end of 2014. In 2015, gas could supply more than 70% of the region’s gas needs, and the percentage increases through the end of the decade, with 90%-plus of demand supplied.

By 2020, Marcellus production alone could be pumping as much as 20 Bcf/d of gas and 900,000 b/d of liquids, dramatically outpacing regional demand.

“That is a lot of new supply in a relatively short period of time, so it should come as no surprise that the old pipeline network was quickly stressed and the effort to develop new takeaway capacity is fast and furious” said RBN Energy LLC analyst Housely Carr. “As happened with Rockies gas in the mid-2000s, the pipelines are playing catch-up and will be for some time, leaving a portion of Utica/Marcellus gas constrained for the foreseeable future…

“Note that total Appalachian production has been increasing by about 250 MMcf/d each month since early 2012, but is projected to slow to only about half that rate over the next five years. Much of that slowdown is due to capacity constraints out of the region.”

So, with the Northeast sitting pretty, where does the excess gas go? It could be transported in almost any direction, including overseas, but at a cost.

“It’s not as easy to escape oversupply as you might think,” TPH’s Olsen said. “We’ve seen $15 billion of announced and secured Marcellus projects, and we’re still in early or middle innings. But getting a Northeast pipe done isn’t easy.” As basis has deteriorated, the infrastructure focus has shifted from the Northeast and New York City to the Midwest and Gulf Coast, TPH noted.

“The future of the Marcellus lies in the South, Midwest and Canada,” said analysts. Most of the new pipelines in development, with total capacity of about 6 Bcf/d, are “non-Northeast, so producers agree.”

With about 80 wells a month being drilled in the area, boasting initial production rates of 4 MMcf/d to as much as 25 MMcf/d or more, the pressure is on. “That’s huge,” said Carr. “The situation is not as dire in Utica/Marcellus as it was in the Rockies a few years ago, but it’s not pretty either.”

The result, he said, “has been sometimes yawning basis differentials this summer,” versus Henry Hub pricing at some of the regional trading hubs that include Tennessee Gas Pipeline Zone 4 Marcellus (TGP Z4 Marcellus) and Dominion South. “TGP Z4 has been more than $2.00 below Henry. Dominion South, which moves gas in the area near the eastern terminus of REX, has averaged about 35 cents/MMBtu below Henry.”

Pennsylvania’s dry gas producers are challenged to ensure their gas has access to Northeast markets and in some cases are “striking innovative deals” to sell to local distribution companies (LDC), or LDCs with legacy long-haul pipeline capacity from the Gulf Coast and elsewhere.

“Basically the LDC replaces Gulf Coast supplies with nearby Appalachia supplies on the same pipelines they have been using for decades,” including Tennessee and Transco.

There is a lot of new and updated infrastructure being developed as well.

Takeaway Capacity, Now and Later

Northeast demand, hugely weather dependent, now ranges from 5 Bcf/d to 22 Bcf/d, according to TPH research. Subscribing to a 50 cent/Mcf pipeline “can make a mint on cold days, when basis between Pennsylvania/West Virginia and Boston hits $20-30/Mcf. During the remainder of the year, the same shipper could be paying to move across low or negative basis.” The average pipeline tariff for Marcellus pipeline projects, including short-haul lines that don’t deliver into a market, costs roughly 50 cents/Mcf, with some more than $1.00/Mcf.

A Williams executive said recently that laying a pipeline through the heavily populated region is more expensive and demanding than laying deepwater pipes in the Gulf of Mexico. No matter the time and effort, takeaway issues have to be resolved.

In early August Williams had to restrict some gas services on Transco because of capacity constraints in Pennsylvania (see Shale Daily, Aug. 2).

More than half of the natural gas pipeline projects that entered service last year were in the Northeast, according to the Energy Information Administration (EIA). The two largest projects added to the Northeast in 2012 — Dominion Transmission Inc.’s Appalachian Gateway Project and Equitrans LP’s Sunrise Project — both move natural gas from Marcellus production fields to northeastern markets.

Despite that capacity increase, “the import-export capability in the Appalachian region is really starting to feel tapped out,” Genscape Inc. senior natural gas analyst Andy Krebs toldNGI. Analysis of the region, including compressor station flows on Transco, indicates that “we have displaced all gas that we potentially can; we have pushed back everything that we can to Canada” (see Shale Daily, July 10).

“In fact, we’re exporting out of the Niagara Spur now; there’s no import volumes from Canada. There’s really no import volumes on Tennessee, Tetco and Transco, and in particular this spring, we’ve seen a big pushback on Transco and Tetco. And then on top of that we’re pushing back as much volume as we can to the Midwest,” Krebs said.

The 120-mile-long, 30-inch diameter pipeline contemplated by Constitution Pipeline Co. LLC is the only actual big gas pipe newbuild in the Northeast today, according to TPH. It would connect Williams Partners’ gathering system in Susquehanna County, PA, to the Iroquois Gas Transmission and Tennessee Gas Pipeline systems in Schoharie County, NY. Plans are for it to ramp up in 2015 (see Shale Daily, June 17). Most of the new Marcellus infrastructure, however, involves compressing existing pipelines, looping, and replacing old segments.

The Marcellus bounty is restructuring older systems. Rockies Express Pipeline LLC (REX), designed to carry gas from the Rocky Mountains east, now is working on approvals to move Marcellus gas west (see Shale Daily, Sept. 12). However, REX is far from the only game in town, said Carr. “For example, a joint venture of Spectra Energy, Enbridge and DTE Energy has proposed building the $1.2 billion-plus Nexus pipeline,” a 250-mile line that would carry up to 1 Bcf/d from northeastern Ohio to outside Detroit, then move to the existing Vector Pipeline to serve the Ontario market.

“Nexus is no quick-fix though; the project needs a long list of regulatory approvals, and its co-developers don’t see it coming online until late 2016 at the earliest” Carr said. Also in the works are TransCanada’s Lebanon Lateral, the Texas Eastern (Tetco) Uniontown, PA, to Gas City, IN expansion; and the TGP-Utica Backhaul to carry gas from Tennessee to the Gulf Coast.

TransCanada, which has seen volumes on its west-to-east mainline across the continent drop from 6.8 Bcf/d in 2000 to 2.4 Bcf/d, is working on converting part of the line to hauling oil.

Just this week ANR Pipeline Co. announced two open seasons for projects to make over portions of its Lebanon lateral to bi-directional flow intended to give Marcellus and Utica shale gas access to the pipeline’s markets in the Midwest and Gulf Coast (see Shale Daily, Sept. 24b).

In the right now, however, initial service could begin by the end of September for two projects that would increase Marcellus takeaway capacity by a combined 0.5 Bcf/d, according to an EIA pipeline status review. The two projects are a 7.9 mile loop, the “313 Loop,” added to Kinder Morgan’s Tennessee Gas Pipeline and a 2.5 mile link between NiSource’s Columbia Gas Transmission and a 1,329 MW gas-fired Dominion power plant. EIA said these would be the first of several takeaway projects planned for completion this winter.

Over the next couple of months, Tetco’s Tennessee Northeast Upgrade project should be in service, transporting northeastern Pennsylvania gas on the 300 Line to Spectra Energy’s Algonquin pipeline to feed New York and New Jersey markets. “In the same timeframe, Transco’s Northeast Supply Link project will get gas from their Leidy Line that runs through the northeast Pennsylvania shale window also into New Jersey and New York,” Carr noted.

Wet v. Dry Gas

It may seem counter-intuitive to ramp up more drilling — not necessarily more rigs. However, the returns are better than might be imagined.

“The reason many companies continue to drill in the Marcellus despite depressed gas prices is because of the play’s superior economics and also because of its high NGL content,” said Motley Fool’s Sreekumar. “An assessment by Standard & Poor’s last year found that the Marcellus is easily the most economical shale gas play in the country. “With natural gas prices of $3.50/MMBtu, Marcellus ‘dry gas’ wells generate an internal rate of return [IRR] of around 12%, while Marcellus ‘wet’ gas wells generate an IRR of close to 30% due to the higher revenues associated with NGLs…”

Dry gas activity mostly is concentrated in four Pennsylvania counties, Susquehanna, Wyoming, Lycoming and Bradford, where operators generate an after-tax rate of return (ATROR) of about 10% at prices of $1.75-3.50/Mcf, according to TPH. Southwestern Pennsylvania wet gas output mostly is in Washington, Ohio, Wetzel, Ritchie, Tyler, Doddridge, Harrison and Marshall counties, where operators can achieve a 10% ATROR at less than $1.50/Mcf.

Because of the “big difference” in prices, there has to be an incentive for south- and west-bound backhauls, and ultimately, firm contracts from the region, according to analysts. The northeastern part of Pennsylvania, i.e., the dry gas region, has an estimated gathering/transport price of about 60 cents-$1.25/Mcf. In the liquids-rich southwestern region of the state, those costs are estimated at 35-85 cents.

Roadblocks are ahead as dry gas meets wet gas, said Carr.

“The natural gas pipeline capacity situation for producers in southwestern Pennsylvania, Ohio and West Virginia, where wet gas is king, is not quite so constrained, but it is still challenging. One problem shared by producers in eastern Marcellus and Utica/western Marcellus is that their distinct areas act as roadblocks to each other. That is, there is a ‘traffic jam’ between the two areas.”

When dry gas is moved southwest, it eventually will run into wet gas surplus from the region, he said. “Consequently, for many producers in Northeast Pennsylvania, it will make the most sense to take one of the routes out of the region,” northward to displace Canadian imports; into New Jersey, New York and New England on one of the pipeline projects; or around the constraints along the Atlantic Seaboard to displace gas that has traditionally moved up from the Gulf into Virginia and points south.

Moving supplies Northeast from the wet gas areas also will see the same kind of roadblocks from dry supplies. “So the best way out for those producers is the other way — moving west, northwest and south into the Midwest markets and all the way down to the Gulf.” There’s also the potential of moving Marcellus gas that’s liquefied to overseas markets from the proposed Dominion Cove Point export facility in Maryland; it received initial approval from federal regulators earlier this month (see Shale Daily, Sept. 13).

Getting Better and Better

As for producers, they are doing what they can to move their development costs ever lower. The industry may be getting closer to figuring out how to standardize lateral lengths and hydraulic fracture (frack) spacing. Over the next two years, the new norm for longer laterals is expected to be 5,000-8,000 feet with tighter frack spacing. The days to drill also is falling dramatically, with wells completed in less than 20 days — about half the time it took in 2010. And estimated ultimate recoveries also are improving.

“We estimate initial wells saw 1-2 Bcfe per 1,000 feet of lateral, versus current numbers of 1.5-3 Bcfe/1,000 feet,” TPH analysts said of the Marcellus. “In general, the industry is heading toward 150-200 foot spacing per frack stage to optimize completions.”

The top operators in the play expect much more activity ahead.

Cabot Oil & Gas Corp. said it increased its output between April and June by 52% to a record 95.2 Bcfe from the same period of 2012, mostly on the back of its predominantly Marcellus acreage. Range Resources Inc., with a commanding one million net acres in Pennsylvania, reported year/year gains in the period of 27%, averaging 910 MMcfe/d. Chesapeake Energy Corp. said its dry gas production in the Marcellus jumped year/year in the three-month period by 58%, with wet gas output up 56%.

At a recent conference, Noble Energy Inc. COO Dave Stover said the company has increased its wet gas activity in the Marcellus this year, mostly focused in West Virginia, with less drilling in its dry gas acreage. “But I’d say the economics of both have held in very stellar through actually the lower gas price environment.”

The production increases have led to a growing backlog of wells with no place to go. In the first six months, Pennsylvania’s backlog jumped 8% from a year ago to 1,545, according to state regulators.

New and improved infrastructure eventually will begin to make a dent, and then, look out. Gas production, wet and dry, could expand even more.

“Gas producers have…become more efficient as they adopt pad drilling, extend laterals, and realize significant improvements in well performance,” said the Barclays analysts. “This is in line with our view that gas production for 2014 should grow faster than in 2013.”

At the Barclays CEO Energy-Power Conference earlier this month, EQT Corp.’s management team said it expected to see 70% year/year production growth this year, partly because of reduced cluster spacing. Cabot highlighted that the average estimated ultimate recovery (EURs) of wells drilled in 2012 was as high as 14 Bcf, almost double that of wells drilled in 2009.

“Costs continue to fall, and returns are attractive even with current gas prices and a basis discount of 20-25 cents to Henry Hub for the region,” according to Barclays. “Some producers are adding rigs to the play, while others plan to maintain or reduce drilling activity. Several major producers are moving to pad development in the Marcellus next year and project company-level production growth in the region.”

Conference participants noted that Marcellus production will reach markets in Canada, New England and Long Island, NY, in 2015 and beyond as a result of infrastructure expansion.

Each operator has a strategy to get their gas to market for a viable return. For Cabot, it’s all about New England, while Range depends on flow assurance from its gas consumers to mitigate contract coverage. According to TPH, Range has signed a 200 MMcf/d deal that would come online by 2015 but it didn’t disclose the project; REX indicated recently that it signed a mirror deal with an undisclosed producer.

Chesapeake, meanwhile, has aggressively contracted some Marcellus region expansions, but that type of contracting has been questioned by analysts. It costs more than $1.00/Mcf to ship into the rapidly saturated New York City market, which also carries the highest average expansion costs (65 cents/Mcf), TPH noted. Anadarko Petroleum Corp. has subscribed to Transco’s Leidy Southeast, evidence of its desire to “get away” from the New York market and push into the Mid-Atlantic.

Don’t forget about the impact from the Utica and Upper Devonian targets.

Utica gas production in January was estimated at about 120 MMcf/d, but it could climb to 550 MMcf/d by the end of 2013, according to analysts. Another 250 MMcf/d on average may be added every year after that. The Upper Devonian, meanwhile, is seeing a pick up in activity adjacent to Marcellus wells. EQT has said the Upper Devonian may not be prolific on its own, but it’s economical when wells are developed incrementally to the Marcellus. Chesapeake is projecting its Utica production will reach 330 MMcf/d net by year’s end from 85 MMcf/d at the end of June.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |