NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report | E&P | NGI All News Access

Facing Dismal Market Conditions, Mexico’s Pemex Urged to Choose Profits Over Production

As oil prices continue to fall amid the worsening coronavirus pandemic and an oversupplied crude market, Mexican state oil company Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex) must make a choice between production and profitability, according to new analysis by Welligence Energy Analytics.

Assuming a $35/bbl Brent crude oil price, 78% of Pemex’s producing fields are cash flow negative, researchers said late Tuesday, a day on which Mexico’s crude oil export basket fell to $18.78/bbl, compared to an average of $55.63/bbl in 2019.

The Welligence team argues that Mexico should slash Pemex’s 2020 capital expenditure (capex) budget by 70% and redirect funds to the top tier fields; improve the fiscal regime for the bottom tier fields to avoid losing taxes by halting production; and announce “a massive farmout program by year-end.”

These measures “would improve cash flow immediately, allow Pemex to reduce losses on those bottom fields without losing tax revenue,” and improve Pemex’s liquidity via signing bonuses from the farmouts in order to reduce the 100% state-owned company’s crushing debt load, said Welligence’s Pablo Medina, vice-president of research.

Pemex, whose full-year financial losses nearly doubled to $18 billion in 2019, “faces a clear trade-off between profitability and production growth,” researchers said, adding, “maximizing positive cash flow generation should be the priority.”

Colombia’s 88.5% state-owned oil company Ecopetrol SA on Tuesday announced a $1.2 billion reduction in 2020 capital spend in response to the dismal market conditions, saying it plans to prioritize production and cash flow.

For Pemex to follow suit would “be a tough pill to swallow” for the López Obrador administration, “whose priority is production growth,” Welligence analysts said. However, “If handled correctly, Pemex could find itself on a healthier path that re-opens the door to outside investors.”

Listen to the latest episode of our newest podcast NGI’s Hub and Flow via:

Episode 1: What You Need To Know About The Mexico Gas Market Today

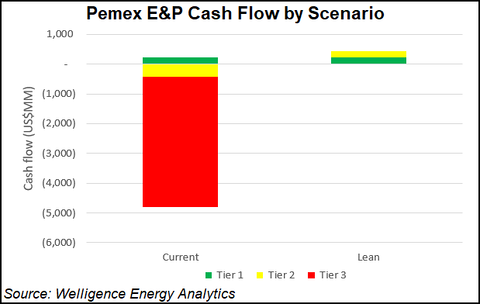

The Welligence team divided Pemex’s portfolio of more than 200 onstream fields, which produce about 1.6 million b/d of oil, into three tiers.

Tier one includes 16% of fields, which are profitable even with new drilling, and which supply around 60% of production currently. These include Ku-Maloob-Zaap, Xanab and Tsimin.

Another eight percent of fields are in tier two, defined as fields which are profitable but cannot support new drilling, such as Ek-Balam, Ogarrio and Abkatun. These fields supply about 15% of production.

Finally, tier three fields, which account for 76% of the fields, are “cash flow negative regardless.” These include mature fields in the Tampico-Misantla basin, as well as the Chicontepec field.

The tier three fields supply 25% of production but absorb over 55% planned investment in 2020, analysts said, noting that these include most of Pemex’s priority fields, on which it has staked a plan to reverse declining production in 2020.

In a November note, Welligence said that 90% of those fields have a breakeven Brent oil price exceeding $50/bbl, and that only two — Ixachi and Xikin — “should be developed, if any.”

Welligence is proposing a “Lean Pemex” scenario in which capex is slashed from an $8 billion base-case scenario to $2.2 billion, with growth capex directed only to the most profitable assets, and less than 10% of the 400 planned development wells are drilled.

Tier two fields could continue producing, but with no additional drilling, while tier three fields “should be shut in, as their cash costs are higher than current oil prices.”

Although production would fall to under 1 million b/d, the plan would result in almost $450 million of positive cash flow, analysts said.

Although Mexico president Andrés Manuel López Obrador has effectively closed the country’s oil sector to new private investment, “the inevitable deterioration in the finances of Pemex, and therefore the government, could force change,” Welligence analysts said.

The team highlighted that Pemex only hedged about 15% of its 2020 production at a $49/bbl Maya crude oil strike price, independent of the finance ministry’s hedge of around 30% of production at the same strike price.

On Wednesday, Mexico employers association Coparmex urged a course shift at Pemex, citing that the Mexican basket price had fallen to its lowest level since 2002.

“The response from President López Obrador to the fall in the oil price has been, ”we must produce more,’ a decision that translates to greater losses,” Coparmex said, adding that the government must “put aside its obsession with refining oil,” a reference to the Dos Bocas refinery project that is projected to almost surely generate sizable losses for the state company.

“The López Obrador government must focus the efforts of Pemex on exploration,” the group said, and resume farmout tenders for acreage operated solely by Pemex in order to relieve the strain on public finances.

In a twist of irony, Wednesday marked the 82nd anniversary of the expropriation of Pemex by then-president Lázaro Cárdenas.

In a packed ceremony that took place as governments around the world closed their borders and ordered citizens to self-isolate in a frantic effort to slow the spread of the Covid-19 virus, López Obrador waxed nostalgic about the 1938 oil nationalization and criticized the 2013-2014 energy reform that opened Mexico’s oil segment to private investment.

He warned that although he will respect exploration and production contracts awarded under the reform, “the privatizing period is over,” signaling that Pemex farmouts are unlikely to resume in the near future.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |