NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report | Coronavirus | E&P | Infrastructure | Markets | NGI All News Access

U.S. Upstream Operators Like to Cut Activity, Capex as Markets, Crude Prices Plummet

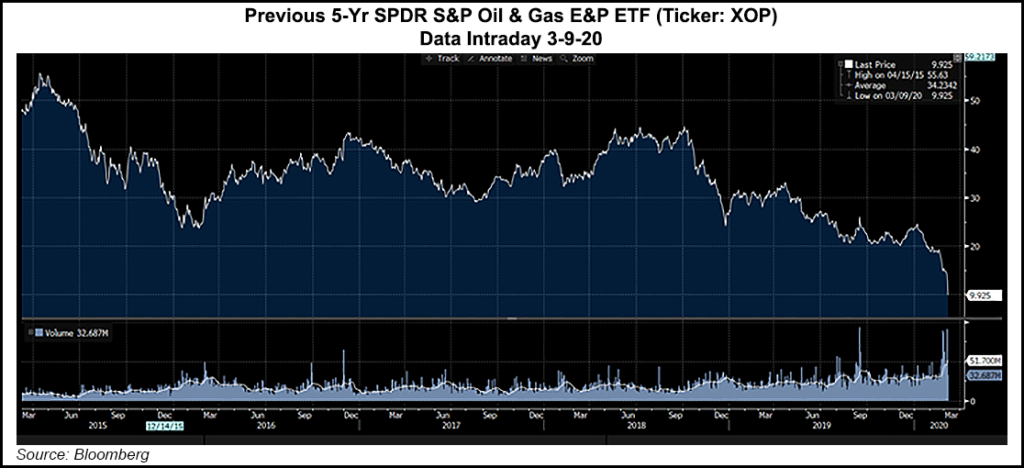

Investors fled stocks early Monday and crude prices plunged by double-digits as a price war between Russia and the Saudi-led oil cartel raged and the uncertainty of the coronavirus spooked global markets.

The Saudi-led Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) last week recommended members and allies reduce oil output through the rest of the year, beyond a voluntary deadline of March 30, with additional reductions through June. However, ally Russia balked, leading Saudi Arabia Oil Co., aka Aramco, to cut prices and basically launch a price war.

Market reaction was devastating.

“The failed deal will have serious consequences for the U.S. upstream sector, with a significant decline in operators’ drilling and completions spend in 2020,” analysts with Tudor, Pickering, Holt & Co. (TPH) said Monday. Independent exploration and production (E&P) companies could reduce their 2020 spend by 25-30% if oil were to fall below $45/bbl, with “a meaningful deceleration of 2020-plus crude production growth.”

The TPH analysts said the “OPEC/Russia brinksmanship…has now devolved into a full-blown battle for crude oil market share, the reactions of the commodity, equity and debt markets are all saying loud and clear that no energy companies (or oil export-dependent countries) across the world or across the industry value chain will be immune from battle wounds.”

Russia Energy Minister Alexander Novak said OPEC-plus would be free to produce “at will” beginning April 1, which could mean an oil price in the $20s “could be on the horizon,” the TPH analysts said.

In fact, Permian Basin pure-play Diamondback Energy Inc. on Monday became the first Lower 48 E&P to publicly react, announcing it is immediately cutting completion crews to six from nine, and it plans to drop two rigs in April and release another one by the end of June.

“As a result of current and expected oil price weakness, we have immediately reduced development activity and expect lower activity levels to continue until we see clear signs of commodity price recovery,” Diamondback CEO Travis Stice said. “We believe that while this is clearly a challenging time for our industry, these are the conditions that Diamondback is prepared for.”

Because expected returns of the 2020 program have declined, “we have decided to wait for higher commodity prices to return to growth. We have flexibility on all of our rig and completion crew contracts, and are well protected with hedges this year for a majority of our production, all of which will allow us to exit this downturn from a position of strength.”

BofA Global Research analysts said Brent and WTI oil prices could “temporarily dip into the $20s range over the coming weeks.” Brent price forecasts were cut to $45 from $54, with WTI forecast to dip to an average of $41 from $49.

Societe Generale analysts cut their 2Q2020 average Brent price to $30, down by a whopping $25 from a previous forecast. “We forecast average Brent prices to remain very low in 3Q2020 at $35/bbl,” off $22 from the previous outlook. By the final three months of this year, Brent should recover to $40 on average, still down $18 from its previous forecast.

Previously during periods of demand shock, oil prices have bottomed at cash costs, which now are about $23 WTI for U.S. E&Ps and $26 WTI for Canadian oilsands producers, said Goldman Sachs analysts.

There’s usually a lag of a couple of months before U.S. E&Ps respond to prices, the Goldman analysts noted, but “we see the response time narrowing given flexibility of shale and greater focus on free cash flow (FCF).”

Goldman analysts expect Lower 48 operators initially to move to the lower end of their annual capital expenditure (capex) guidance ranges. “This would not necessarily have that material an impact on 2020 production in part because we believe some companies have buffers in their production guidance and will also defer noncompletion activity (infrastructure, exploration, drilling).”

By late April and early May, E&Ps could reduce capex even further, impacting production in late 3Q2020 and into 4Q2020, “with a potentially more powerful impact into early 2021,” said the Goldman analysts.

Goldman’s team does not expect the majors to make immediate adjustments to capex, particularly ExxonMobil and Chevron Corp., which last week each reiterated strong growth forecasts for the Permian this year.

“However, if oil prices are in the $30s/bbl WTI, we believe some shale slowdown is likely. We expect much lower activity outside our coverage due to expectations for lower cash flow from private/other producers. We believe this could begin to impact rig activity in the coming weeks.”

Before the price war between OPEC and Russia, Goldman was guiding to U.S. oil growth this year of around 0.6-0.5 million b/d at an average WTI price of $55.

“If producers were to begin lowering activity into 2Q2020 under expectations for a $35-40/bbl WTI oil environment through mid-2021, we see a scenario in which U.S. oil production falls by 0.2 million b/d year/year on average in 2021.”

“The price collapse could be the trigger for a new phase of deep industry restructuring, one that rivals the changes seen in the late-1990s,” said Wood Mackenzie’s Tom Ellacott, senior vice president of corporate upstream. “Indebted Lower 48 producers could be forced to act sooner rather than later.”

The last oil price war was about five years ago, but this time oil demand also is weak because of the viral outbreak. “The macroeconomic backdrop is completely uncharted waters for oil and gas companies,” Ellacott said. Even so, the oil and gas industry’s financials are in better shape following actions they took with the price collapse that began in late 2014.

Wood Mackenzie’s Fraser McKay, head of upstream analysis, calculated that up to $380 billion of cash flow would vanish from forecasts if Brent prices averaged $35 for the remainder of the year, representing an 80% drop relative to a continuation of the $60 averaged year-to-date.

“Sustained prices below $40 would trigger a new wave of brutal cost cutting,” McKay said. “Discretionary spend would be slashed, including buybacks and exploration. But given the lack of excess in the system, the cuts to development activity will be necessarily fast and brutal.

“U.S. tight oil development activity, though not as flexible as many believe, will react immediately. Unsanctioned conventional projects will also be delayed, and infill, maintenance and other spend categories scaled back.”

Moody’s Investors Service also weighed in on the implications for oil and gas operators. “The OPEC decision adds an oil supply shock to the demand shock already being felt from Covid-19,” said Steve Wood, managing director for Oil & Gas.

“Moody’s has already been assessing companies’ exposure to weaker commodity prices as a result of the virus,” Wood said. “We will be focusing on individual company liquidity and creditworthiness as this situation evolves including the extent to which hedging mitigates short-term spot price volatility, as well as assessing company resilience in a range of pricing scenarios. The price shock will particularly affect companies with refinancing needs over the next six-to-12 months.”

American Exploration and Production Council CEO Anne Bradbury offered a more optimistic view, noting U.S. E&Ps plan for short-term disruptions, and they structure operations “to be nimble, as we continue to operate safely and efficiently to provide the world with American energy.”

The U.S. energy industry, she said, “provides our allies with safe and clean energy, while protecting our national security interests. Sound regulations and policies that enable U.S. independent producers to continue leading the world in energy development are needed to ensure that our allies do not need to rely on Russian-produced energy and that our country retains the energy independence we sought for decades.”

The International Energy (IEA), already scheduled to issue its latest global oil market forecast, said unsurprisingly Monday demand is expected to decline this year because of Covid-19, with the impact “constricting travel and broader economic activity.

“The situation remains fluid, creating an extraordinary degree of uncertainty over what the full global impact of the virus will be,” IEA researchers said. In its central base case, demand this year is seen declining for the first time since 2009 because of the “deep contraction” in China’s oil demand, as well as major disruptions to global travel and trade.

“The coronavirus crisis is affecting a wide range of energy markets — including coal, gas and renewables — but its impact on oil markets is particularly severe because it is stopping people and goods from moving around, dealing a heavy blow to demand for transport fuels,” said IEA Executive Director Fatih Birol.

“This is especially true in China, the largest energy consumer in the world, which accounted for more than 80% of global oil demand growth last year. While the repercussions of the virus are spreading to other parts of the world, what happens in China will have major implications for global energy and oil markets.”

The IEA is forecasting global oil demand now to decline to 99.9 million b/d in 2020, down around 90,000 b/d from 2019. IEA in February had predicted global oil demand would grow by 825,000 b/d this year. “The short-term outlook for the oil market will ultimately depend on how quickly governments move to contain the coronavirus outbreak, how successful their efforts are, and what lingering impact the global health crisis has on economic activity,” according to the global energy watchdog.

“The impact of the coronavirus on oil markets may be temporary,” Birol said. “But the longer-term challenges facing the world’s suppliers are not going to go away, especially those heavily dependent on oil and gas revenues. As the IEA has repeatedly said, these producer countries need more dynamic and diversified economies in order to navigate the multiple uncertainties that we see today.”

The Covid-19 “crisis is adding to the uncertainties the global oil industry faces as it contemplates new investments and business strategies,” Birol said. “The pressures on companies are changing. They need to show that they can deliver not just the energy that economies rely on, but also the emissions reductions that the world needs to help tackle our climate challenge.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |