NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report | Infrastructure | Markets | NGI All News Access

Column: Will 2020 See New Capacity Opportunities for Marketers in Mexico?

Editor’s Note: NGI’s Mexico Gas Price Index, a leader tracking Mexico natural gas market reform, is offering the following column as part of a regular series on understanding this process, written by Eduardo Prud’homme.

Prud’homme was central to the development of Cenagas, the nation’s natural gas pipeline operator, an entity formed in 2015 as part of the energy reform process. He began his career at national oil company Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex), worked for 14 years at the Energy Regulatory Commission (CRE), rising to be chief economist, and from July 2015 through February served as the ISO chief officer for Cenagas, where he oversaw the technical, commercial and economic management of the nascent Natural Gas Integrated System (Sistrangas).

The opinions and positions expressed by Prud’homme do not necessarily reflect the views of NGI’s Mexico Gas Price Index.

This year, all the projects included in the first five-year plan drawn up by Cenagas in 2015 as part of the energy reform for natural gas should, in theory, be operating. Yet, while there has been tremendous progress in the Mexican gas market, there are pending projects and objectives outlined back in 2015 that are far from being achieved.

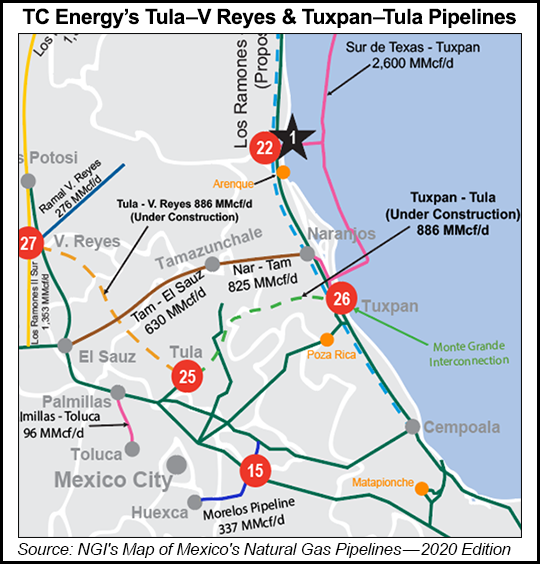

The suspension of work on the Tuxpan-Tula pipeline certainly dents the overall strategy outlined in the plan. This pipeline is the first segment of a zigzag path that connects eastern Mexico with western Mexico through the heart of the national territory. The Tuxpan-Guadalajara corridor would in theory also provide connectivity to the large north-south trunks that feed the Mexican market with cheap imported gas. Now, this connectivity will occur in a segmented way.

Instead of the gas from the marine pipeline in Aguascalientes being added to the gas originating in Waha, the almost-done Wahalajara system operated by Fermaca will see split flows in this area. A stream will be directed as originally planned to the west to the Guadalajara area while a counterflow stream will go east to the town of Villa de Reyes. There are no clear public announcements regarding the dates of operation of these sections, but it is likely that the pipeline that goes to Guadalajara will start operations in the coming weeks while the stretch that goes to Villa de Reyes will probably operate before summer.

The second segment of the zigzag is the Tula-Villa de Reyes pipeline, which is set to run from east to west. Its capacity will be used by U.S. gas coming from the marine pipeline. But since the first part of the project is now suspended for at least two more years, it will probably operate in the opposite direction, receiving gas from the Fermaca pipelines to supply generation plants in Tula and Salamanca.

Also not part of the original plan, but included as part of the annual reviews carried out by Cenagas as the entity responsible for maintaining natural gas balance in Mexico, is the reconfiguration of the Cempoala station, a key to the continuity of supply in the southeast and central parts of the country. Although some specialists in the sector who follow the operational information of the Sistrangas pipeline system have the suspicion that Cempoala has already entered into operation, the truth is that as of February 20 there are still supervisory works ongoing on the turbocharger. The expectation is that it will enter into operation before the annual rebound in demand begins in April.

Overall, infrastructure plans have advanced. As a result, despite physical and operational obstacles, contractual disagreements and recent changes in operating philosophy, critical alerts and shortages should continue to remain a thing of the past in 2020. If production declines in the southeast do not spiral out of control, continuity of service should be taken as a given in an economy that consumes 7 Bcf/d in a transport network that together can move more than 12 Bcf/d – even if the capacity of a network is a slippery concept, as noted in previous columns.

What remains to be seen is the fulfillment of the underlying aspirations of the 2015-2019 plan. The execution of the different projects was part of the commissioning of a new transport and marketing model for natural gas in Mexico. The intention was to increase and diversify supply options in a competitive environment with open access guarantees, and clear and transparent rules. It was also designed to move from a system in which a vertically integrated supplier held a monopolistic position (Pemex) to a market with multiple molecule suppliers and logistics services.

Under the current administration, Pemex has concentrated its efforts on combating the theft of liquid fuels in its pipelines and maintaining its credit quality in order to increase financial resources. In this sense, the incumbent gas marketer does not seem to be the biggest threat to the formation of a market with options for users. Despite a massive campaign to promote its brand sponsored by the government of Mexico, the historical reputation of the oil and gas giant and increased awareness means users are more eager to get interconnected to the transport network managed by Cenagas to achieve firm capacity through different supply options.

The problem lies elsewhere. With new supply contracts in place or budding, marketers have strived to increase the capacity achieved through the 2017 open season or in subsequent bilateral assignments in the incipient secondary market. Consequently, each entry into operation of a new pipeline generates the expectation that a new capacity allocation process should occur, either in the Sistrangas or in private pipelines that are not integrated.

The operational impact of both the marine pipeline and the Wahalajara system coming online encourages shippers to see a scenario in which CFE, the anchor client on the pipes, meets all its generation needs fully with primary routes that run through all systems, leaving ample operational capacity for ambitious marketers to serve existing and new industrial customers and distribution areas.

The gas consumption of power plants in El Encino, Tamazunchale, Altamira, Tula, Salamanca, Villa de Reyes, Poza Rica, Tuxpan, Dos Bocas, San Lorenzo and Valle de México is such that by migrating to the new systems this not only opens up transport space on the Sistrangas, it also leaves idle capacity on the new systems. Almost half of the routes that originate in Camargo, the starting point of the Ramones system, are destined for electricity consumption points. Clearly, if CFE yields or resells the capacity associated with this injection point, marketing opportunities would increase dramatically in the northeast and central parts of the country.

The suspension of the Tuxpan-Tula pipeline leaves 1 Bcf/d stranded, while an expansion of the interconnection in Montegrande and the entry into operation of Cempoala would strengthen the reliability of gas supply in the central area of the country, one of the most relevant in national economic activity. The process of transfer or release of capacity can be implemented in a creative way to maximize economic value for CFE, to improve the operation of the system and to avoid operational shocks in other regions.

But the market is very large and can lead CFE into capacity-building behavior. Looked at as a competitive strategy or in an environment of austerity, the payment of charges for unused capacity is not justified, and in the case of CFE, it will eventually have an upward effect on electric rates. To date, CFE announcements suggest that its intention is to implement a commercial platform that takes advantage of all its available contracts. There is no sign that augurs a massive capacity release. This, in spite of an obligation to do so as established by the hydrocarbons law.

The principle of “use it or lose it” is set in the legal framework of fuel supply in Mexico. Given the market paradigm, the experience in the gas industry led to recognition that the market fails at times and needs regulatory intervention. It is here that CRE is essential. It is up to this regulatory body to set the rules and mechanisms to characterize hoarding, to design remediation mechanisms and to force their application.

But CRE is not acting. There is no known public consultation or discussion of the issue by the regulator. What we have seen is preferential treatment to the arguments raised by state companies. Some commissioners have endorsed the “rescue PEMEX and CFE” rhetoric. And at the end of January, an agreement of the plenary of commissioners led to a public consultation on whether to invalidate rules regarding open seasons.

The commissioners say they seek to establish the most appropriate regulatory scheme that generates incentives to achieve efficient allocation and use of capacity, which allows the development of a secondary market that it intends to form.

But the issue remains in the air. The final result will undoubtedly involve political motivations, in the same way that the negotiation of contracts was resolved last year. We will probably see transfers of capacity, on a case by case basis, and with differentiated treatment. The opportunities will be there for players other than Pemex and CFE, but these players will need a good dose of patience and an ability to adjust expectations and tactics.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |