Infrastructure | NGI All News Access

Billion-Dollar Central America Pipeline Project Once Again on the Table in Mexico

Plans unveiled recently by the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation to finance a $632 million natural gas pipeline in southern Mexico could be the start of a new and more ambitious project for the gasification of Central America, Alejandro Giammattei, president-elect of Guatemala, told a gathering of business leaders in early November.

At a meeting in Mexico with President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, Giammattei said the two leaders had pledged to construct what is in effect an extension of the southern Mexico pipe, across the border and into what is known as the Northern Triangle of Central America, Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador.

In all of Central America, only Guatemala has production of hydrocarbons, currently a little less than 9,000 boe/d, almost all of it produced by Perenco, which claims to be the leading independent oil and gas company in Europe today.

Overall in Central America, geothermal energy, hydroelectricity and renewables, including wind and solar, are in the mix, but natural gas has clear advantages, according to the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (Eclac).

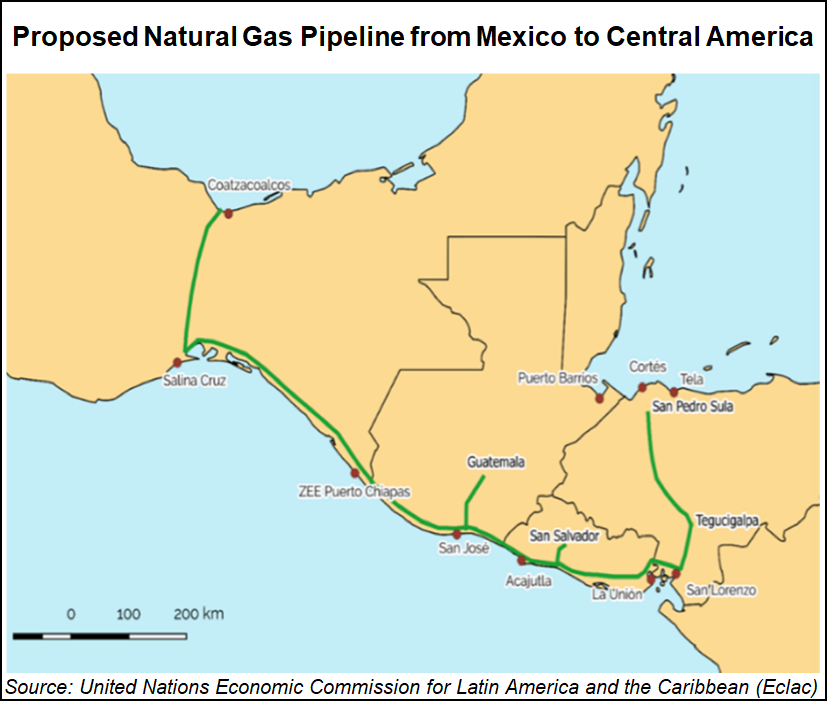

Their calculations are based on an extension of the southern Mexico pipe, which would bring U.S. gas from the Pacific Coast port of Salina Cruz to Tapachula on the Guatemalan border. From there the pipe is planned to run from the Gulf of Fonseca in El Salvador and on to the port of Puerto Cortes, where a combined-cycle plant is set to be built. This would come at a price tag of $1.2 billion, according to Eclac.

At the presentation of the plan last year, David Jiménez González, Mexico’s ambassador to Honduras, said that the pipeline “will kick-start the economy of the region and stem at least part of the emigration of people fleeing from poverty and violence.”

Not everyone is convinced, however. Miriam Grunstein, chief energy counsel at Mexico City-based Brilliant Energy Consulting, and a nonresident scholar at the Center for the United States and Mexico at Rice University’s Baker Institute, told NGI’s Mexico GPI that she doubts that the project will succeed, “not least because of questions of public security and the financial scale of the investment.”

The pipeline project has, indeed, a long and unsuccessful history. It was part of the Pueblo-Panama project launched in 2000 by President Vicente Fox that aimed to generate prosperity in southern Mexico and Central America.

Within about a year, tenders were invited but nobody responded.

Interest was revived under the 2012-2018 presidency of Enrique Peña Nieto, when several meetings with Guatemalan officials on the pipeline issue were held.

Meanwhile, natural gas has made its entrance in Central America in the form of a reception terminal and regasification plant accompanied by a combined-cycle unit that have been built by AES in Panama.

In addition, a similar complex is being built at Acajutla, El Salvador, on the Gulf of Fonseca. What is known as the Energía del Pacífico project is being built by Chicago-based Invenergy LLC and El Salvador’s Quantum Energy.

The $1 billion price tag of the Energía del Pacífico investment is the largest ever of any infrastructure project in El Salvador, and it has been part-financed by $300 million from the US Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC).

Alejandro Alle, executive director of Energía del Pacífico, a native of Argentina, is a skeptic on the Central American pipeline project. “When I got to El Salvador,” he told NGI’s Mexico GPI, “people were telling me that soon gas would be piped in from Mexico, but it hasn’t happened yet.

“Meanwhile, it should be noted that there are less expensive, low-impact alternatives to a pipeline in countries like El Salvador where industry and commerce is mostly on a very small scale, with correspondingly modest demands.”

That may be so, but political leaders — in Mexico, Guatemala and perhaps in the United States — are likely to have the last word.

Giammattei and López Obrador are expected to have, if not the last, at least a very important word on the issue, when the former is inaugurated on January 14. The trip is set to be the Mexican president’s first foreign visit since taking office.

López Obrador has skipped even major economic summits and the United Nations General Assembly, quipping that “the best foreign policy is domestic policy.” But he seems particularly keen to keep his neighbors happy.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 |