Regulatory | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

COLUMN: Forming Local Index Is Crucial to Developing Mexico’s Natural Gas Market

Editor’s Note: NGI’s Mexico Gas Price Index, a leader tracking Mexico natural gas market reform, is offering the following column as part of a regular series on understanding this process, written by Eduardo Prud’homme.

Prud’homme was central to the development of Cenagas, the nation’s natural gas pipeline operator, an entity formed in 2015 as part of the energy reform process. He began his career at national oil company Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex), worked for 14 years at the Energy Regulatory Commission (CRE), rising to be chief economist, and from July 2015 through February served as the ISO chief officer for Cenagas, where he oversaw the technical, commercial and economic management of the nascent Natural Gas Integrated System (Sistrangas).

The opinions and positions expressed by Prud’homme do not necessarily reflect the views of NGI’s Mexico Gas Price Index.

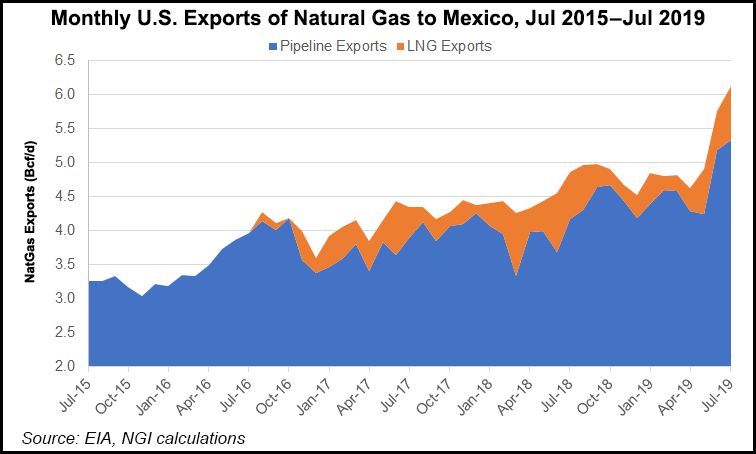

Growing gas supply in Texas from the Permian Basin and Eagle Ford Shale is perfectly suited to meet rising demand for gas in Mexico, especially as domestic production from the Burgos Basin and the Southeast falls. These underlying dynamics will see increased gas flows from north to south of the border during the next five years, but pricing will be important to consolidate an efficient market.

Historically, large gas users in Mexico have used a price formula associated with the wholesale price issued by Pemex, known as the first-hand sales, or VPM price.

This formula was regulated by the CRE and followed a netback logic from a reference market. From that competitive market, at that time alien to the national monopoly of Pemex, a differential was estimated that sought to emulate a basis in the United States; a transport cost of one of the routes that MGI, the international commercial arm of Pemex, used to import MGI gas was added or subtracted. With this calculation the price of gas that Pemex delivered in the Reynosa area was formed. The price of gas sold in the Southeast in Pemex City, was determined from that plus the transportation cost involved in determining the points of confluence.

Prior to the energy reform, the netback formula involved adding the Reynosa-Monterrey route and subtracting the Cardenas-Monterrey fare as the point of confluence was the Los Ramones compression station in the Monterrey tariff zone. The reference price was the Houston Ship Channel, and then later on, the CRE decided to change to the Henry Hub index. With the changes in the tariff zones that resulted from the first five-year review of the National Gas Pipeline System (SNG), the transportation component to reflect the opportunity cost at the points of confluence amounted to the sum of the Gulf stamp minus the South stamp.

The essential mechanics of this formula prevailed for a decade with some minor modifications and with certain regulatory dilemmas. On the one hand, the pressure of interest groups, mainly industrial users, questioned whether the indices in the southern United States were exempt from Pemex’s influence. If this were the case, the price formula would allow Pemex to appropriate an income to the detriment of the efficient balance required in a competitive market. On the other hand, underestimating the opportunity cost of the gas produced in Reynosa involved placing a barrier to entry to potential marketers who could not make a competitive offer consistently.

As part of the first open season on the Sistrangas pipeline system to provide transportation service on a firm basis, this regulatory dilemma was overcome when the CRE decided to eliminate the price formula from the conditions of the VPM model. This competitive decision to promote openness did not necessarily ensure that users would automatically obtain the benefits of new market entrants. The reason is simple: opening in the Sistrangas was not necessarily accompanied by an equivalent opening of the capacity of the cross-border pipes in possession of the commercial arms of Pemex and CFE.

A timid attempt to obtain a transfer of capacity to achieve a greater number of shippers in the intrastate pipeline of NET Mexico occurred with the auction of 750 MMcf/d of capacity arranged by the Ministry of Energy with Pemex and organized by Cenagas in February 2017. BP Energía de México and a couple of industrial users took about 220 MMCf/d in the auction. The public rate set as the reserve price was 31 cents/MMBtu.

Subsequently, on an electronic bulletin board (EBB) designed to facilitate more auctions, Cenagas convened five auctions of transport capacity belonging to CFE Internacional. Although several marketing companies registered on the Cenagas EBB, none presented a proposal to obtain capacity on a daily basis in the Net Mexico pipeline or annually in the cross-border pipelines that connect the Waha hub in the Permian with the systems tendered by CFE in the northeast of Mexico.

The departure rates were $0.1358/MMBtu in the Transpecos pipeline to deliver gas to Ojinaga, and $0.1858/MMBtu in Comanche to deliver gas in San Isidro. In the El Paso Natural Gas system, CFE was willing to transfer capacity on the Wilcox side for delivery in Agua Prieta for $0.1926 USD/MMBtu and in the San Agustin area for $0.3928/MMBtu. At the Road Runner pipeline, on the path connecting the Oneok system with Cactus, CFE sought to place capacity with an exit fee of $0.37 USD/MMBtu.

The reasons why the auctions were unsuccessful have to do with the connectivity of these routes with pipelines on the Mexican side, and with liquidity opportunities at demand centers that are still to be created.

In the post-energy reform world, the formation of prices at the cross-border points is a critical ingredient in the efficient development of the market, because the intermediation strategies of the commercial arms of Pemex and CFE will be determinants of the level of competitiveness downstream in the centers of consumption within Mexico.

The risk is that such entities, which are subsidiaries of state-owned companies, follow a strategic behavior with a view to achieving surpluses to the detriment of competition. Basically, Waha prices that look so attractive to Mexican consumers might not end up being that way if these state companies manipulate their pricing. The occurrence of this phenomenon outside Mexican territory also hinders the legal action of regulatory bodies to police it.

Once the gas is sent across the U.S. border into Mexico, the multiple routes that connect the border with the north and center of Mexico will entail different gas prices at several of the points of confluence that will exist as interconnections between systems occur. The diversity of supply sources will allow a price differentiation that in turn will help incoming marketers to the Mexican market gradually gain customers in the group of Mexican users who have historically sought alternatives to the monopolistic supply of Pemex.

The emergence of market centers may be the wedge that gradually opens up the conditions for greater competition in the importation of gas from Texas. Among the points and regions that may be favorable, the Monterrey area stands out for obvious reasons. It is the most important industrial consumer center in the country with sophisticated users who understand the energy market, has two distribution areas, including the largest in Mexico operated by Naturgy, and has several access routes to gas from Texas.

The gas can reach the Monterrey area from the Sistrangas managed by Cenagas, by Kinder Morgan in the system that is born in Mier and by the Nueva Era pipeline originating in Webb County in South Texas. From Sistrangas, different shippers can carry gas from different systems in South Texas, such as NetMex, Energy Transfer, Kinder Morgan Border, Tennessee and even Tetco. Put like this, a header that connects the Sistrangas, with Kinder Morgan and Nueva Era in the area of Pesquería could be the first Mexican Hub with possibilities to serve as a base for a first Mexico price index.

A less obvious area that can be dynamic thanks to the entry of the marine pipeline is the one that is around the city of Querétaro in the center of the country. It is an industrial zone with economic growth, with a couple of distribution zones run by Igasamex and Engie. In terms of supply, the area receives imported gas via the 48-inch diameter Sistrangas pipeline, and in recent years the connection of the second phase of the Ramones project, TAG Pipeline South, in Apaseo el Alto has improved the conditions of gas availability in the area. To the south of the city of Querétaro, at a point known as Pedro Escobedo, the Huasteca pipeline, owned by TC Energy Corp., is delivering gas from the Naranjos interconnection to the marine pipeline.

To this confluence, the potential effect of the gas that the Fermaca system will drive from the Waha area and that could be injected into Sistrangas at the point of El Castillo, in the vicinity of Guadalajara to go in the direction of Bajío and Querétaro, must be added. That is, in the area there will be a confluence of gas that will have traveled the four north-south trunks of the country from the Agua Dulce hub in South Texas and Waha in the Permian with different prices of origin and different rates per route, and therefore, with different values for end users.

The nature of transport fees adds diversity to prices in the entire Mexican gas network. Sistrangas has a list of rates by zones that result from the allocation of the regulated income requirement of six of the seven systems that comprise it, and the standard tariff set almost two decades ago. The aggregate requirement is updated annually by changes in the exchange rate and inflation in Mexico and the United States in accordance with the rules set by the CRE.

Each individual permit is subject to rate revisions in five-year regulatory periods, so it is expected that variations will occur depending on the service cost review. In the other systems that are not part of the Sistrangas, although they follow the same logic of annual updates and rate revisions every five years, it is expected that the effective rates for shippers will be differentiated: tariffs related to the rate for users other than CFE while that the latter must pay the fees resulting from the tenders he held or those resulting from the renegotiations that took place this year. Clearly, the observable price landscape will not resemble the past mechanics of the netback formula. Traceability and understanding of price shaping can be done from specialized surveys in the North American way.

Demand growth needs market transparency. To the extent that there is more confidence on the part of the users around the offers made to them by marketers, there is clarity that they are not being transferred distorted costs or inefficiencies of a monopolized or congested system, and long-term commitments can be made.

In the future, having contracts referenced only to Henry Hub or Waha will not be a sufficient condition for users to manage their risks. It’s essential we get to a more local signal. Otherwise, the lack of transparency regarding the value implicit in a basis between Texas and Mexico may generate doubts that will encourage or postpone business decisions related to additional gas consumption. The price report issued by the CRE, the National Wholesale Price Index of Natural Gas (IPGN) is a good dissemination effort but the fact that it implies data delivery to an authority means there is less willingness to be transparent.

Private efforts to publish price information are thus crucial to the market in Mexico. In the coming years, the contribution that agencies such as NGI in the publication of data around transactions will be a key catalyst to greater liquidity and depth in the gas market. And soon, a Mex index will be added to the list of National Balancing Point, Title Transfer Facility, Houston Ship Channel and Henry Hub as a reference for transactions.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |