Regulatory | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Interconnections, Capacity Clarity Said Needed in Mexico Natural Gas Market

Mexico’s natural gas market needs more clarity as to how its two main pipeline systems will interact, from both a physical and regulatory perspective, according to Talanza Energy Consulting’s Daniela Flores, head of midstream and downstream.

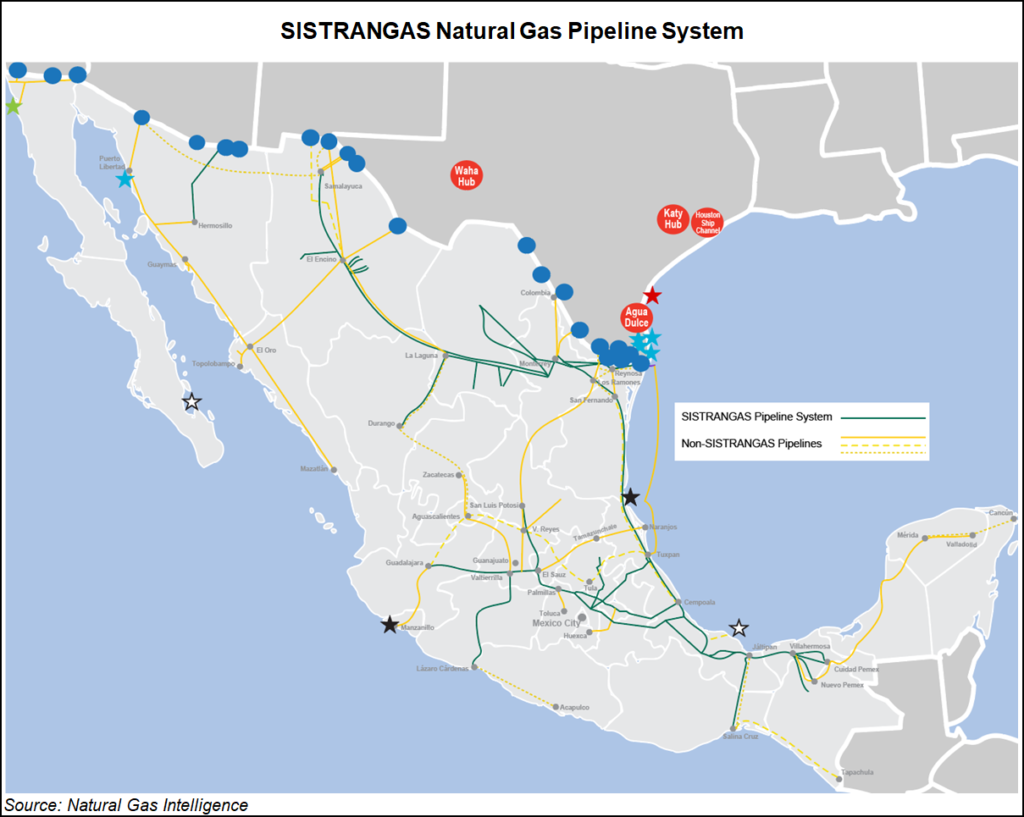

The Sistrangas national pipeline grid is operated by the Centro Nacional de Control del Gas Natural (Cenagas), and spans about 6,256 miles.

A separate set of pipelines is anchored by CFEnergía, the fuel marketing arm of state power utility Comisión Federal de Electricidad (CFE), and operated by private sector pipeline firms. These pipelines, on which CFEnergía is the sole shipper, stretch 3,739 miles.

The distinction is “important because there are different stakeholders with different rules and approaches,” Flores told the US-Mexico Natural Gas Forum in San Antonio, TX, on Tuesday.

The Sistrangas operates under open access rules, which require Cenagas to offer non-discriminatory treatment to all shippers seeking to move gas on the system. Rules established by the Comisión Reguladora de Energía also mandate the “use it or lose it” principle, under which shippers must release idle capacity.

On the CFE pipelines, however, there are still “no rules” and there is “no transparency” on how CFE will allocate its excess capacity, Flores said.

A recent audit of CFE by the Auditoría Superior de la Federación (ASF) found that CFE in 2018 only utilized 16.6% of its reserved capacity on 17 pipelines in operation.

Although Mexico boasts some 11 Bcf/d of pipeline import capacity via more than 20 interconnection points with the United States, Flores said, “it doesn’t matter” if end users can’t fully access that capacity.

“CFEnergía has not yet awarded, or has not yet had a contract with anybody in terms of this capacity that they have in the pipelines,” Flores said. “They are just focusing on their generation plants, so that is a problem for the final user.”

Another pending challenge is increasing the number of interconnections between the CFE and Sistrangas pipes.

The recently completed, CFE-anchored 2.6 Bcf/d Sur de Texas-Tuxpan marine pipeline feeds into the Sistrangas at the Montegrande interconnection.

However, another three crucial interconnections between the CFE and Sistrangas systems – El Encino, Guadalajara, and Mayakan – are still pending.

The Mayakan hookup, which is essential for gas to flow from the Sistrangas to the gas-starved Yucatán Peninsula, is not expected until 2020.

The Mayakan pipe is currently fed by production from national oil company Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex) from shallow water fields off Mexico’s southeastern coast.

Through a swap arrangement with CFE, Pemex injects this gas into the Cactus processing center, and receives gas from CFE a few hundred miles up the coast at Altamira, where CFE imports liquefied natural gas (LNG) via the Altamira terminal, and piped gas via the Sur de Texas-Tuxpan pipeline.

However, the quality of the gas injected by Pemex at Cactus “is still very questionable,” Flores said, underlining the urgency of the Mayakan interconnect.

The 100 MMcf/d El Encino tie-in, meanwhile, will connect the Sistrangas with Fermaca’s El Encino-La Laguna system, and is expected for this year, according to an October report by energy ministry Sener.

The 250 Mmcf/d Guadalajara interconnect will link the Sistrangas with the Gasoducto de Zapotlanejo S. de R.L. de C.V. (GAZA) system, and is slated for this year as well, according to the Sener document.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |