Regulatory | NGI All News Access

Regulatory Changes Said Needed in Latin America to Attract Oil, Gas Investment

Without a more pro-market oil and natural gas regulatory framework in place, Latin American countries may not reach their full potential as investors could steer clear from pouring money into the industry, key executives said recently.

In Houston last month for Gastech 2019, BP plc’s Felipe Arbelaez, regional president of Latin America, said that as the region has shifted from hydrocarbon scarcity to abundance, the oil and natural gas industry needs to look carefully at how to spend its capital. This is especially important as, similar to the United States, the wealth of resources in Latin America has left regional commodity prices lower than they have been in decades.

Argentina’s Vaca Muerta formation has elevated the country to natural gas production king as majors including Royal Dutch Shell plc, Malaysia’s state-owned Petroliam Nasional Berhad (aka Petronas), BP plc and Qatar Petroleum have committed billions to explore the formation. Chevron Corp., ExxonMobil Corp., Equinor ASA and Total SA have also ramped up their activity in the play.

But Latin American plays as a whole account for about one-third of global large and giant prospects expected to be drilled this year. Unless the government and regulatory agencies across the region become aware that they need to generate efficiency and send the appropriate price signals to the market, “capital won’t come and resources will stay underground,” Arbelaez said.

However, policy overhauls across Latin America cannot be carried out with a one-size-fits-all approach. In the Caribbean, for example, not all the islands have the same characteristics and needs, according to Timmy Baksh, director of energy research and planning at the Ministry of Energy and Energy Industries in Trinidad and Tobago.

“Each island has different needs and wants. For example, not all are prone to hurricane risk. Therefore, one portfolio may not address all the issues of the Caribbean,” Baksh said. “Project developers need to look at synergies that can be achieved between clusters of islands.”

In Brazil, the country is working toward improving energy policies that will stimulate competition in its new open natural gas market launched this year. Under the plan, Brazil’s state-owned oil company Petroleo Brasilerio (aka Petrobras) will completely exit the transportation and distribution sectors by the end of 2021, making room for private investment and competition.

As part of that divestment program, Petrobras plans to sell Transportadora Associada de Gas, or TAG, which operates a gas pipeline network in the north of Brazil.

“We are in a new environment in Brazil now,” said Symone Araujo, director of natural gas at Brazil’s Mines and Energy Ministry. “We have to become business friendly in order to attract investors.”

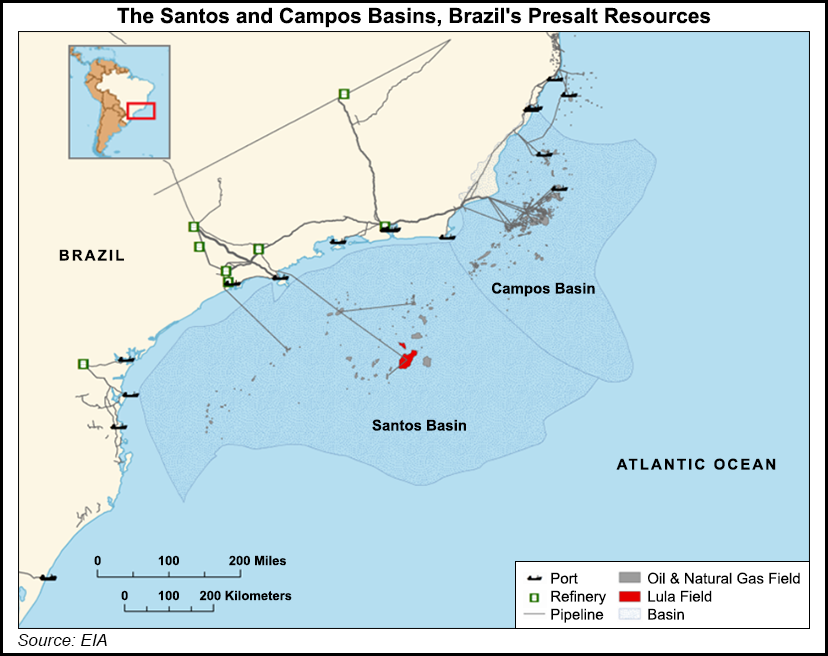

Around 80% of Brazilian gas is extracted offshore, due mainly to the rapid development of the pre-salt deepsea area, one of the fastest growing oil patches globally, according to the International Energy Agency. Hydrocarbons regulator Agência Nacional do Petróleo, Gás Natural e BiocombustÃveis expects oil production in Brazil to double to 5.5 million b/d by 2027 on the back of offshore production.

However, pre-salt operators in Brazil have expressed concern that they can’t proceed with associated gas programs because they don’t have access to pipelines and midstream infrastructure. Instead, gas is often reinjected or flared.

“We don’t have a problem of supply. But we have a bottleneck of transmission,” Araujo said. “It’s important to develop new midstream infrastructure in Brazil.”

However, there are also concerns about demand. After reaching an all-time high of 4.154 Bcf/d in 2015, natural gas consumption in Brazil dropped to 3.473 Bcf/d in December 2018, according to global economic data firm CEIC. This was also a decrease from December 2017, when consumption hit 3.641 Bcf/d.

Demand is also a concern for Argentina’s state-owned YPF, which is partnering with Petronas in the La Amarga Chica joint venture and separately is developing a 5 million metric ton/year (mmty) liquefaction facility to serve producers developing the Vaca Muerta.

“We need demand to happen,” said YPF vice president of gas and energy Marcos Browne. “We’re looking to national companies that have stepped into the Vaca Muerta and will wait to see if demand is real.”

The company earlier this year pumped the brakes on upstream natural gas investment and was forced to curtail gas output because of an excess of supply compared to domestic demand.

While subsidized wellhead prices for unconventional gas have spurred investment in shale and tight sand formations in Argentina, the ramp-up of production has coincided with an economic slowdown in Argentina, where gross domestic product is expected to shrink for a second straight year in 2019. As a result, the government earlier this year said it would be limiting subsidies for unconventional gas.

As for the liquefaction project in development, Browne said that YPF has “learned quite a lot” through its Vaca Muerta wells, and it “can compete on the game level as other projects around the world.”

Argentina LNG is projected to ramp in 2024 as production volumes reach 6 mmty, which could then grow to 10 mmty by 2030, according to Wood Mackenzie. Argentina in June exported LNG for the first time in its history, with LNG produced on Exmar NV’s floating LNG production barge called Tango FLNG using natural gas piped in from Vaca Muerta in the western part of the country.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 |