Regulatory | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Natural Gas-Rich Pennsylvania to Join Cap-and-Trade Group RGGI

Pennsylvania Gov. Tom Wolf has signed an executive order (EO) setting the state on a path to join the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI), a move that could prove transformational for the cap-and-trade program among nine Northeast and Mid-Atlantic states.

Members develop individual frameworks through legislation or regulations that comply with RGGI’s aim to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from the power sector. Wolf’s EO directs the Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) to draft regulations for the state’s Environmental Quality Board. If they’re approved, a public comment period would follow.

RGGI states include all of those in New England, Maryland, New York and Delaware. New Jersey adopted rules earlier this year to rejoin the program. But unlike the other members, Pennsylvania is a major energy producer, with a power sector that is still somewhat coal-heavy.

“Given the urgency of the climate crisis facing Pennsylvania and the entire planet, the commonwealth must continue to take concrete, economically sound and immediate steps to reduce emissions,” Wolf said. “Joining RGGI will give us that opportunity to better protect the health and safety of our citizens.

Wolf, a Democrat, indicated that the process to join the program could take two years, an ample opportunity for what ClearView Energy Partners LLC said could allow “Republican opponents to force the governor to either weaken or halt the rulemaking altogether.”

State House Republican leaders signaled their intent to complicate the process, saying “our state is not an autocracy.” Bills are in the works to prevent Pennsylvania from joining RGGI or implementing other programs, such as a carbon tax.

“We believe the executive branch cannot bind the state into multi-state agreements without the approval of the general assembly, and we plan to execute the fullest extent of our legislative power on behalf of the people of Pennsylvania,” House leadership said.

Senate Republicans, meanwhile, said the next steps in the process must preserve the diversity of the state’s energy portfolio, protect state consumers, require that other RGGI states utilize all of Pennsylvania’s energy production and allow the legislature to weigh in.

Republican state Sen. Gene Yaw, who represents parts of Northeast Pennsylvania that account for much of the booming natural gas production there, took to Twitter and said, “it’s clear to me we have very little in common” with New York, New Jersey and “other New England states. How can we have a common interest with them when they prohibit the importation of our gas? They thumb their nose at Pennsylvania gas, and embrace and purchase gas from Russia!”

Yaw was referring to other member states that have resisted pipeline projects that would connect more Appalachian natural gas to the Northeast. Contrary to his claim, the United States does not import Russian gas, Energy Information Administration (EIA) data shows. A cargo of liquefied natural gas that originated in Russia was unloaded from a French ship at a terminal near Boston last year in what Engie SA told NGI at the time was a one-off deal to serve the region during a harsh cold snap. The incident has been widely cited by critics of New England’s energy policies.

Executive director Dan Weaver of the Pennsylvania Independent Oil and Gas Association said Republican comments are a strong indication that “there’s going to be an interesting fight” over the EO going forward. Weaver said he remains concerned about how the state’s possible membership might impact gas-fired power generators, which have become a significant source of local demand for Appalachian shale production.

“It’s one more hurdle,” he told NGI. “We’re already dealing with a struggling market for our producing community because of low commodity prices and basis differentials, and now one of the local outlets for moving gas is going to be under attack. It’s just one more hurdle to jump.”

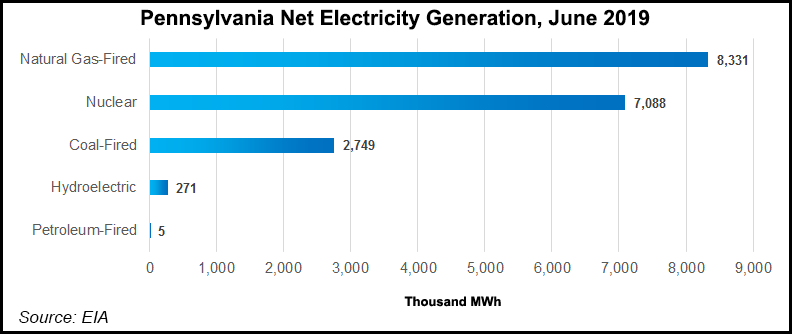

Pennsylvania is the nation’s second largest producer of gas, the third largest electricity and coal producer, and second in overall energy generation, according to the EIA. However, it’s also the fourth highest emitter for carbon dioxide (CO2), surpassing other RGGI members. ClearView noted that if Pennsylvania joined RGGI it would address a key concern in the region about pollution “leakage” and prove a milestone for the cap-and-trade program.

Since 2005, when RGGI governors signed the agreement, RGGI has cut CO2 pollution by 45% in the region. Under the program, power generators in participating states must purchase credits for each ton of CO2 they emit. The program has netted more than $3 billion for member states since 2009 when the cap took effect. Those proceeds have been dumped back into renewable energy, energy efficiency or other environmental measures.

While power generators in Pennsylvania could pay millions of dollars under the program, the Wolf administration said because the state exports nearly one-third of the electricity it produces, the cost of compliance would be passed through to consumers in other states. The Pennsylvania Chamber of Business and Industry (PCBI) expressed skepticism.

“We encourage legislative input and an analysis of costs to ratepayers and the industry in order to ensure that the commonwealth’s approach to greenhouse gas regulations is balanced, making sure to leverage the state’s great energy assets and encourage private sector competition without stifling potential economic growth,” PCBI CEO Gene Barr said. “Climate change is real and so is the need to have the business community at the table to discuss solutions and consider the tradeoffs.”

Moreover, gas-fired electricity output exceeded coal-fired generation last year for the first time in the history of PJM Interconnection, the grid operator serving 13 states and the District of Columbia, including Pennsylvania. Natural gas units, which have continued to gain more of the region’s power stack in recent years as Appalachian production has driven down prices, accounted for 30.6% of PJM’s generation mix in 2018. Dozens of gas-fired facilities have been built or are under construction in the region, many in Pennsylvania.

The Electric Power Supply Association (EPSA), which mostly represents independent gas-fired generators, also signaled that it wants to be “an active participant in any discussions going forward” about Pennsylvania’s role in RGGI.

“We support competitive, nondiscriminatory market-based mechanisms that allow all resources to compete to meet environmental goals,” EPSA CEO Todd Snitchler told NGI.

Industry representatives pointed to the role gas has played in curbing emissions in the state. Between 2005 and 2015, according to DEP’s latest Greenhouse Gas Inventory, carbon emissions fell from 122 million metric tons (mmt) of CO2 equivalent to 86 mmt. The decline coincided with an increase of gas-fired power, which rose from 5% of the state’s generating capacity to 27% over the same time.

The Wolf administration said DEP would “conduct robust outreach” to the business community, energy producers, and labor and environmental stakeholders as it drafts regulations.

Earlier this year, Wolf signed an EO directing state government to cut carbon pollution. In 2016, he launched a methane reduction strategy, which included stronger permitting requirements for new unconventional gas wells and some midstream facilities that took effect last year. His administration has also been working on draft regulations to curb emissions from existing oil and gas production operations.

The announcement to join RGGI came less than three weeks after a bipartisan group of lawmakers pushed Wolf to do more to control methane emissions, especially as the federal government has rolled back regulations. It also comes at a time when his party is taking a stronger stance on climate change nationwide as states implement 100% renewable energy mandates and call for decarbonization.

Environmental groups hailed Wolf’s decision to join RGGI.

“The regulatory strategy outlined…has delivered strong results across the region for a decade,” said the Environmental Defense Fund’s Pam Kiely, senior director of regulatory strategy. “With this template and the intensifying urgency around climate change, we expect the governor’s team will be able to act meaningfully early next year.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |