Regulatory | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

COLUMN: New Cenagas Operating Rules Move Oversight in Right Direction

Editor’s Note: NGI’s Mexico Gas Price Index, a leader tracking Mexico natural gas market reform, is offering the following column as part of a regular series on understanding this process, written by Eduardo Prud’homme.

Prud’homme was central to the development of Cenagas, the nation’s natural gas pipeline operator, an entity formed in 2015 as part of the energy reform process. He began his career at national oil company Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex), worked for 14 years at the Energy Regulatory Commission (CRE), rising to be chief economist, and from July 2015 through February served as the ISO chief officer for Cenagas, where he oversaw the technical, commercial and economic management of the nascent Natural Gas Integrated System (Sistrangas).

The opinions and positions expressed by Prud’homme do not necessarily reflect the views of NGI’s Mexico Gas Price Index.

Changes in the Mexican natural gas market in recent years have added complexity to the physical and commercial operation of the pipeline system. The truth is, the vertically integrated world was easier for operators and users. With a few exceptions in the electricity sector, there were no third parties that were shippers, no defined routes or maximum daily amounts. On two adjoining floors, the marketing and transportation teams of the Pemex subsidiary in charge of natural gas supply paid more attention to operational control variables than commercial considerations.

On the consumer side, each end user consumed gas as tap water is drunk: without notion of the source and how it got to them. Consumption was measured and invoiced volumetrically, without thresholds related to contracted transport capacity.

Then came the gas crisis of 2011 and 2012, significantly restricting supply in large areas of the gas system. The short-term liquefied natural gas (LNG) mass injection solution took a systemic approach, instead of tidying up the specific consumption profiles of users. The solution was weak, and socialized in the transport cost.

Cenagas was created with an explicit legal mandate to contribute to the continuity of natural gas services through effective open access to third parties. Cenagas was also to manage the daily balance of the system.

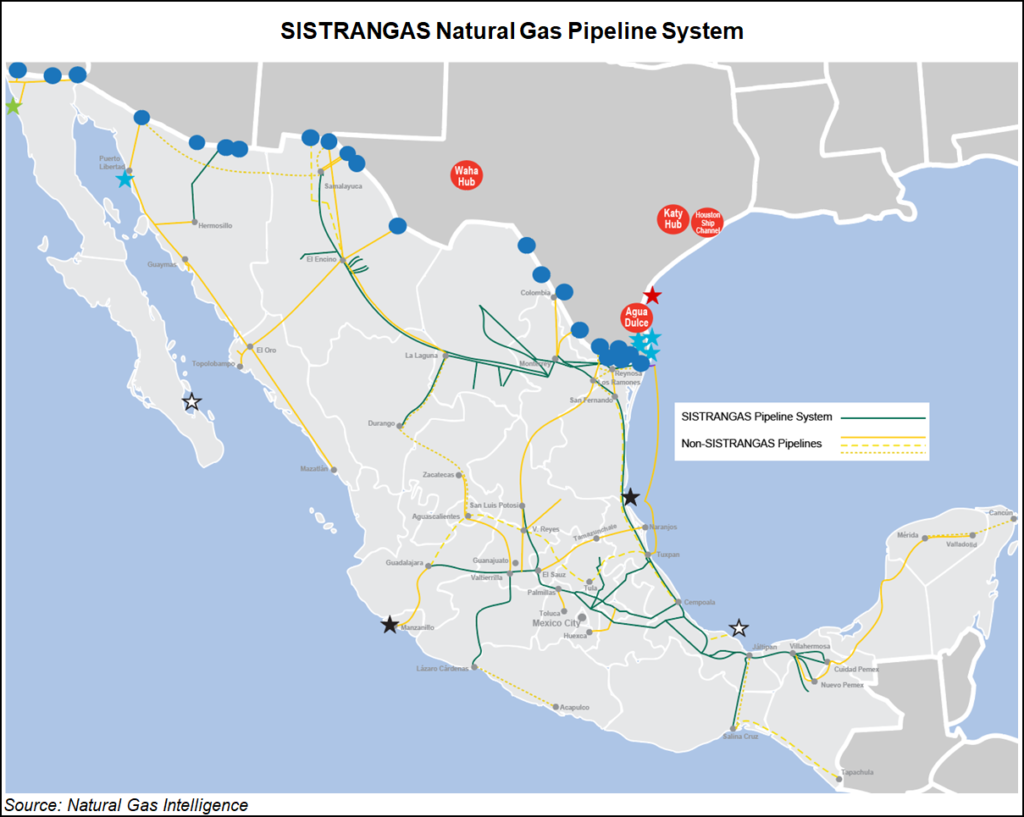

Since July 2017, Cenagas has managed to maintain continuity of supply despite the lack of a regulatory framework for integrated systems. This omission of operating rules hinders Cenagas from accurately assessing the movement of gas throughout the Sistrangas. It is oblivious to operating balance agreements, effective fuel gas efficiency used in the different compression stations, the operating losses of the transport systems not owned by Cenagas, and the measurement at the final consumption points of these systems. In addition, deficiencies in measuring instruments mean that end users share meters so that their volumes consumed have to be estimated.

Without operating rules giving Cenagas the power to collect information from third-party systems and apply coercive measures, the Sistrangas manager has faced serious difficulties in controlling individual imbalances effectively. This situation was further complicated when the CRE decided not only to eliminate the balancing adjustment mechanism as a general measure but also those provisions that allowed it to allocate the cost of injected LNG to users who had notably contributed to the reduction of overall operating conditions. What instead exists is known as the Terms and Conditions for the Provision of Services (TCPS) as drawn up by Cenagas.

The TCPS consists of business rules meant to avoid structural imbalances, facilitate transactions, respect contracts and comply with nondiscriminatory open access. Such rules have as an initial step the reception of orders, or nominations, of each shipper. Orders must clearly define the points of receipt or injection, as well as the location of the points of delivery or withdrawal of the requested service from among the 24 injection points and 162 points of extraction of the Sistrangas. This allows for accurate assessment of quantities of gas that are injected (payback) or withdrawn (makeup) so as to maintain balance of the system or to make adjustments throughout the gas business cycle.

The level of detail of the nomination process has repercussions throughout the business cycle: the nomination is reflected in programmed amounts, assigned transactions, imbalances (a highly sensitive aspect in physical operational exchanges) and often in the way in which natural gas is billed.

Nominations are followed by confirmations that occur between Cenagas and the Sistrangas operators, so that they in turn make their respective confirmations with the upstream system operators, whether with pipelines that interconnect Texas with Mexico or pipelines that they serve before entering the Sistrangas, or with the gas suppliers from the Altamira LNG Terminal and processing centers.

The purpose of this phase is that all operators involved in logistics ensure the consistency of the information they received in the respective gas nominations. This ensures that the gas will arrive from an “upstream” source in the expected quantity, making it possible to take such quantity “downstream.”

Typically, the confirmation processes establish an order of execution to define which restrictions should prevail and which operator on each side of the interconnection is the one that must make adjustments to the orders it has received. If there are significant imbalances, information exchange and order adjustments can occur. Cenagas validates the viability of the flows in the Sistrangas through hydraulic modeling. The confirmed quantities depend not only on the transport capacity in the Sistrangas but also on the availability of gas at the injection points. Confirmation depends on the compatibility with transport contracts with the availability of gas. Hence, each shipper runs the responsibility and risk of having enough gas to occupy its nominated transport.

Programming is the process that follows the confirmations in which the technical feasibility of all the routes is jointly validated, the way in which orders are dispatched and the system will be operated to serve all users. Flows are then executed that can be modified at the request of users or due to operational restrictions that may arise.

Nominations, confirmations, schedules and execution of the flow are stages of the daily commercial cycle of gas transportation that, in theory and with the appropriate monitoring and control equipment, should allow for an orderly service. Payback and makeup transactions allow shippers to adjust imbalances within the same billable period without the need for cashout.

However, this industry practice does not work when system balancing is made with LNG and payments in kind with gas imported by pipeline. When the imbalance size is such that a cash out is imperative, the applicable price is based on a reference such as Henry Hub even though the manager’s purchases were of regasified LNG. This failure of regulation has been very expensive for Cenagas.

With the changes in the direction and composition of the CRE, a window of opportunity opened for a TCPS more in line with the operational reality of the Sistrangas.

On Sept. 1, new Sistrangas operating balance (RBO) rules came into effect. Within the framework of the new RBO, imbalances are the difference in deviations between assigned and scheduled quantities at both reception and delivery points. In the case of these deviations and that they modify the operating conditions of the system, Cenagas has several powers: the ability to modify the quantities of reception and delivery of gas; intervene through the sale or purchase of excess gas; hire additional services such as additional capacity in compression stations, parking, loaning or interruptible services in other systems; and coordinate extraordinary actions with the major market agents: CFEnergÃa, Cenace and Pemex.

The financial viability of Cenagas interventions will be through the obligation of cash settlements associated with the costs incurred. In the same way, for gas injected in excess, the goal will be to park it and then sell it when parking is no longer possible. Cenagas will prorate among shippers the costs incurred for parking and a fraction of the income from the sale with causality criteria for surpluses. In the process of selling said gas, the one willing to pay the highest price will be awarded. If there is a tie in the offers, the award will be with the criteria of first come, first serve.

The RBO includes a list of penalties for deviations from programming and the maximum daily amount put into the contracts. The occurrence of Cenagas interventions will be relevant to define amounts and tolerances regarding such penalties. If once all the penalties and charges of imbalances have been applied, Cenagas has not yet been able to recover the costs incurred for its interventions, a generalized rolling fee may be applied to be included in the rate as a last resort. This fee does not yet have an application methodology approved by the CRE.

Under the new rules, Cenagas can make the liquidation of imbalances in shorter terms enforceable. In the case of nonpayment by a shipper, Cenagas may suspend service without grace periods or even terminate its contract with an almost immediate liberalization of capacity to be assigned to another shipper. In this line, Cenagas can also supervise the measurement, consumption facilities, as well as the operation of the measurement equipment in said facilities through the entire system, at any time that Cenagas deems necessary.

For its part, Cenagas will assume greater responsibilities to provide information to users. The CRE will assign monthly notices of imbalances to each user and the respective charges. In its Electronic Bulletin Board, it will publish the purchases and sales of gas for balancing expressed in terms of volume and energy as well as the costs generated by them, daily at 9:00 a.m., 3:00 p.m. and 7:00 p.m.

As for the imbalances, they will be calculated by Cenagas on a daily basis and accumulated throughout the month of flow by each shipper. In this calculation, makeups are considered at the reception point and paybacks at the delivery points. With the new RBO, an incipient market of imbalances is delineated: if shippers wish to exchange their imbalances, they must notify Cenagas by e-mail once they are notified of the imbalance of the previous month.

Clearly, the new rules imply that shippers devote greater resources, financial and human, to the management of their gas contracts. This change has generated reactions among all agents. What is important is the common knowledge that there is difficulty in overall balancing and there will be no magic solution. Control and measurement equipment must improve so that the economic signals become evident to encourage investment. Regardless of the results obtained from these measures, it is clear that continued dialogue between CRE, Cenagas and the other market agents is needed.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |