Mexico Experts Warn of Lost Oil, Natural Gas E&P Opportunities

By limiting the private sector’s role in oil and gas exploration and production (E&P), Mexico is missing out on opportunities that may not come around again, industry experts told the senate last week.

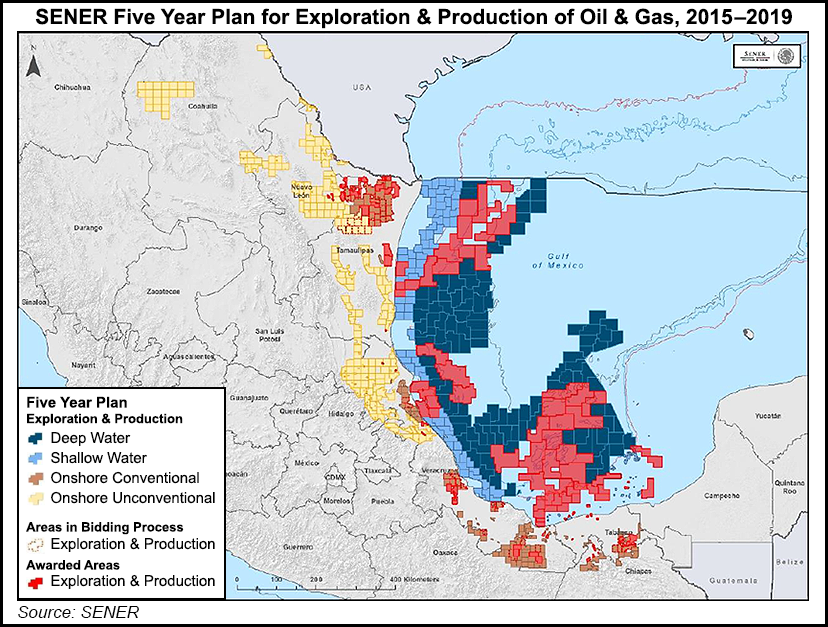

As part of the energy security and sovereignty forum, prominent figures from the public and private energy sectors implored the government to resume bid rounds, promote unconventional drilling, and embrace partnerships with the international oil industry.

The 111 contracts awarded so far through bid rounds, farmout tenders, and service contract migrations under Mexico’s 2013-2014 constitutional energy reform can reasonably be expected to add 500,000 b/d of oil production by 2027, said Asociación Mexicana de Empresas de Hidrocarburos (AMEXHI) director Merlin Cochran.

AMEXHI is a trade group representing oil and gas companies in Mexico.

However, Cochran said, “if Mexico does not continue exploring new areas, production will fall. It’s simply the nature of the industry.”

Since taking office last December, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador has halted the rounds, farmout tenders for operating stakes in acreage held by state oil company Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex), and the migration of oilfield services (OFS) contracts to license or production sharing contracts.

Pemex’s 2019-2023 business plan instead relies heavily on integrated exploration and extraction services contracts, known by their Spanish initials as CSIEEs.

Under this model, the OFS contractor assumes the totality of capital expenditures (capex) and operating expenditures (opex) for the life of a given project, while Pemex retains a 100% operating interest.

The OFS provider is paid a per-barrel fee for oil production and a per-million cubic foot fee for natural gas output.

These arrangements “are not partnerships,” said Miguel Cervantes, founding partner of the energy-focused law firm MCM Abogados.

“They are not what operators seek… I’m not saying they should be abandoned completely, but clearly they don’t work for a certain profile of project,” he told the gathering.

According to its business plan, Pemex seeks to award 40 CSIEEs between 2020 and 2024. Its plan to increase non-associated gas output over the period depends entirely on CSIEEs.

The plan says that Pemex seeks to add 101 MMcf/d of non-associated gas output from the Burgos and Veracruz basins via CSIEEs in 2020, equal to about 10% of the firm’s current non-associated gas production. Pemex sees this figure rising to 147 MMcf/d by 2022, before dropping to 131 MMcf/d in 2023.

However, achieving production from CSIEEs by next year “seems very, very unlikely,” Mexico City-based analyst Gonzalo Monroy told NGI’s Mexico GPI in a recent interview. Monroy said that, during a road show to promote the CSIEEs, Pemex received a “cold shoulder” from drillers.

“Unless they radically change the whole structure of the CSIEEs, it’s not going to happen, at least not in 2020.”

Cochran said that Mexico should follow the example of Argentina, where gas production from the Vaca Muerta shale formation surpassed 1 Bcf/d in December, allowing the country to export its first cargo of liquefied natural gas (LNG) this year.

These milestones would not have been possible if not for collaboration between Argentina’s 51% state-owned oil company, YPF S.A., private sector firms and the local authorities, Cochran said, highlighting that 90% of YPF’s activity in Vaca Muerta has been carried out in joint ventures.

Cochran cited 54 upstream bid rounds either underway or set to launch soon throughout North, Central and South America.

None of these opportunities are in Mexico, Cochran said, “and this, as a Mexican, hurts.”

Cervantes echoed this sentiment, saying that by suspending bid rounds, Mexico “is missing out on an important moment.”

With global oil demand expected to peak between 2035-2040, and given the long lead times for oil and gas projects to reach production, “the time to act is today,” Cochran said.

Senator Armando Guadiana of Coahuila state, who chairs the energy committee, also said that Mexico should embrace hydraulic fracturing to tap the vast shale gas resources in the states of Veracruz, Tamaulipas, Coahuila and Chihuahua.

Rather than endorsing bid rounds, however, Guadiana praised the Bolivian government’s 2006 nationalization of its hydrocarbons sector

“We need…the private sector, [but] with order, and respecting the state, [its] natural resources, and the general interest of the country.”

Deputy energy secretary Alberto Montoya, among the fiercest government critics of the energy reform, said that, “As a result of the policies followed in the recent past, Mexico reduced its capacity to produce the energy it needs.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 |