Regulatory | NGI All News Access

Mexico, Pemex Said Poorly Equipped to Reverse Energy Sector Liberalization

Mexico’s government and national oil company, Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex), are in no position to embark on a reversal of the country’s nascent energy sector liberalization, according to three experts from Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy.

Speaking on Friday at Rice’s Houston, TX, campus, former Pemex CEO Jesús Reyes-Heroles said that President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s vision for Pemex and state power utility Comisión Federal de Electricidad (CFE) is to restore them to the dominant positions they held in the early 1980s, “as if the world had not changed” in the time since.

As a result of the president’s state-centric vision, the government has reversed course from the previous administration’s 2013-2014 constitutional energy reform, which sought to level the playing field for non-state actors and attract sorely needed capital to the sector. But it won’t dismantle the reform, the experts said.

The Baker Institute’s Francisco Monaldi, fellow in Latin American Energy policy, said that to reverse the energy reform would be highly complex.

To be sure, Monaldi said, reversals of energy market liberalization have occurred many times in Latin America, in countries such as Argentina, Venezuela, Ecuador, and Bolivia.

The difference, he said, is that these reversals occurred more gradually, and under more optimal circumstances for the governments in power.

“For example, Hugo Chávez did it five years after he came into power,” Monaldi said of the former Venezuelan president. “And particularly astonishing to me is that in those cases, you had very favorable conditions to reverse policy, in the sense that they occurred after major investment had happened, production and reserves had gone up, and prices had skyrocketed, and as a result, it was a very…easy time to do that.”

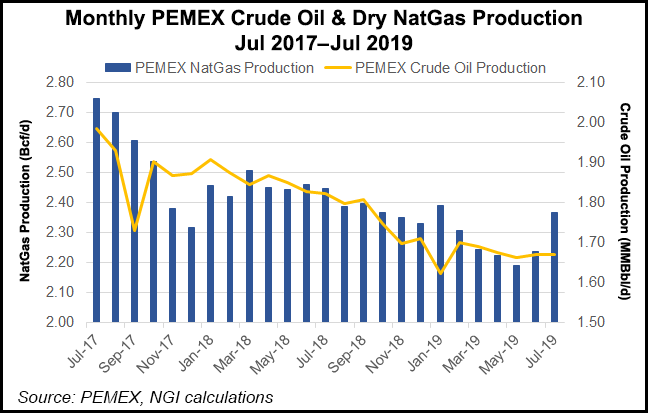

In Mexico, by contrast, Pemex’s production has been on the decline for nearly 15 years. The country’s flagship Maya heavy sour crude oil blend is expected to trade well below sweeter crudes after the International Maritime Organization’s new sulphur restrictions on bunker fuel enter effect in January 2020.

Reyes-Heroles, now a non-resident fellow at the Baker Institute, said that Pemex’s 2019-2023 business plan and proposed 2020 budget are “clearly insufficient, and they clearly won’t allow Pemex to play the role that it is supposed to play in the recovery of our hydrocarbons sector.”

Tony Payan, who directs the institute’s Center for the United States and Mexico, said that the energy reform has been put on hold, but that if anything, any upcoming change would involve a turn toward more openness.

“No one argues that Mexico should have a strong and competitive state oil company,” he said.

“It is the role that such [a] company should play in the broader sector that remains unclear…What is clear is that the energy reform of 2013 and 2014 has been put on hold. It is, however, entirely possible that the Mexican government will eventually realize that it cannot go it alone, and may have to restart it.”

The Baker Institute event coincided with Pemex’s announcement last Thursday that it had completed a $7.5 billion international bond placement, the largest operation of its kind in company history.

The issue was 5.1 times oversubscribed, Pemex said, explaining that proceeds would be used to refinance the company’s short-term debt.

Pemex’s net debt stood at 1.96 trillion pesos as of June 30, or about $100.6 billion at the current exchange rate.

The notes were divided into tranches of seven, 10, and 30 years, with yields of 6.5%, 6.85%, and 7.7%, respectively.

The bond issue was one of three measures announced a day earlier to strengthen the company’s finances.

The other two comprised a $5 billion capital injection from the government to buy back bonds set to mature in 2020 and 2023, and the pending launch of an exchange offer for existing bonds. Pemex said it would release details on the offer once its final conditions were known.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 |