E&P | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report | Permian Basin

Permian Said Likely to See More E&P Consolidation, Continued Bottlenecks as Supply Increases

The Permian Basin, one of the greatest comeback stories in the long history of the oil and gas industry, was given a new and better life with unconventional techniques, and opportunities still exist, but they won’t come without a few challenges, according to research by the University of Houston (UH).

In “Opportunities and Challenges in the Permian,” a white paper commissioned by Hastings Equity Partners in partnership with UH Energy Research, researchers found that major industry consolidation is unfolding as independents muscle their resources to compete against the oil majors.

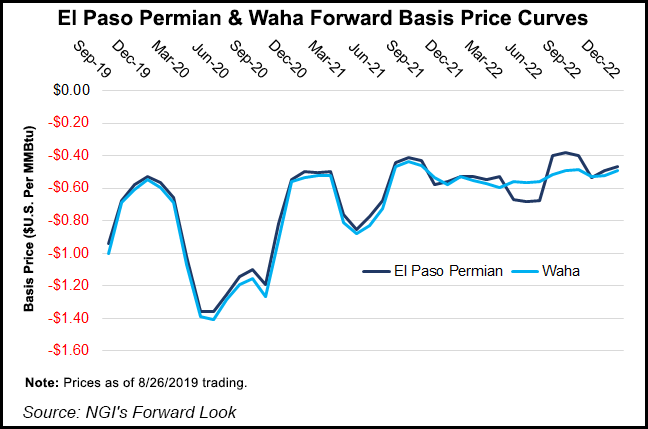

The flowing oil and associated natural gas also face continuing bottlenecks as more pipelines line up to move supply to South Texas and to export markets beyond the border.

“With the Permian Basin predicted to produce an incremental 1 million b/d each year, and the pipeline takeaway issue soon to be resolved with several major new pipelines due to come online in the second half of 2019, Hastings Equity Partners commissioned the University of Houston to find out where the incremental oil is going and to understand the downstream impact that new production levels will have,” said Hastings founder Ted Patton.

“Some facts came out of the research that we didn’t anticipate,” he said, “namely, the impact of the industry consolidation in the Permian Basin and the challenge of how to capture and transport the natural gas that is a byproduct of the process.”

The biggest recent merger was by one of the biggest Permian operators, Occidental Petroleum Corp., which bought Anadarko Petroleum Corp. for, among other things, its prized West Texas assets.

Meanwhile, even the large exploration and production (E&P) companies are facing a big push by deep-pocketed oil majors, led by ExxonMobil and Chevron Corp. The two supermajors alone are projected to produce more than one-half of the oil in the Permian over the next four years, “representing a historic shift in economic power,” according to UH.

ExxonMobil, with 51 rigs and 12 fracture crews in operation, during 2Q2019 saw its Permian output jump 90% year/year to average 274,000 boe/d; it is tracking to increase its Permian output to 1 million boe/d by 2024. Chevron’s Permian averaged 421,000 boe/d, and it expects to deliver 900,000 boe/d in 2023.

“These large companies are consolidating production, resources and supply chains that will meet the majority of domestic needs,” Hastings said. “Their acquisitions of acreage in the Permian, as well as ownership stakes in the pipelines and downstream refineries and petrochemical facilities, mean that smaller independent producers that traditionally sell to the majors will now need to market internationally and export overseas.”

The independent E&Ps initially were the nimble and profitable operators in the Permian, acquiring leases, assets and mineral rights “with more alacrity than their major counterparts.”

However, as the industry’s base in the Permian has matured, the majors have sped up production and decreased margins, basically pushing aside the smaller producers.

“The Permian Basin used to be a place where wildcatters reigned and now, with technology, the economy is being driven by manufacturing,” said Patton.

Independents now face limits from the investment community to reduce production volumes and achieve results with cash on hand.

“The inevitable result will be consolidation by independents in an effort to survive,” Patton said.

As the major producers own refineries and petrochemical facilities, they may not need to purchase supply from from independents. That means finding new customers has become a priority for the smaller players. Independents may need to combine balance sheets to buy downstream assets or form a combined marketing organization to sell their products internationally.

“While refineries have increased processing to keep up with production, supply of crude oil will soon outstrip demand and the producers will need to find new customers,” said UH’s Ramanan Krishnamoorti, chief energy officer and co-author of the research.

More than $90 billion in construction projects now are in place or underway along the Texas and Louisiana coastlines for terminals, liquefied natural gas, refining and petrochemical facilities, and another $200 billion in infrastructure is planned for the next decade, Krishnamoorti said.

Construction overall “can’t keep pace with the supply of oil coming out of the Permian.” Most of the recent incremental oil capacity is expected to continue to be directed to South Texas near the Port of Corpus Christi for export.

An existing obstacle forecasted to persist for the next three years is the ability of very large crude carriers, aka VLCCs, to navigate Gulf Coast waterways to refill for export. Waterways along the Gulf Coast don’t provide the 75 feet of depth needed to accommodate loaded carriers, and hence require ship-to-ship transfers in the offshore.

The demand for crude exporting capabilities also has heightened the need for deepwater terminals. Several projects are on the drawing board, but permitting delays and lengthy construction could hinder progress, creating additional bottlenecks.

Still, many opportunities exist, according to UH. As crude production creates more associated gas, the ability to capture, market and deliver it to potential customers should provide additional revenue streams for producers and service providers.

“Commodity service providers will face continued margin erosion in the fact of customer consolidation and ultimately witness the destruction of enterprise value,” Patton said. “However, differentiated service providers will thrive as long they are able to demonstrate either cost savings or incremental production for their customers.

“These companies provide the rigs, pressure pumping equipment, wireline, wellhead, cement, chemicals and delivery services, and the need is not forecasted to diminish.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |