E&P | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Pemex Charts Its Own Course as Latin American Peers Steer in Opposite Direction

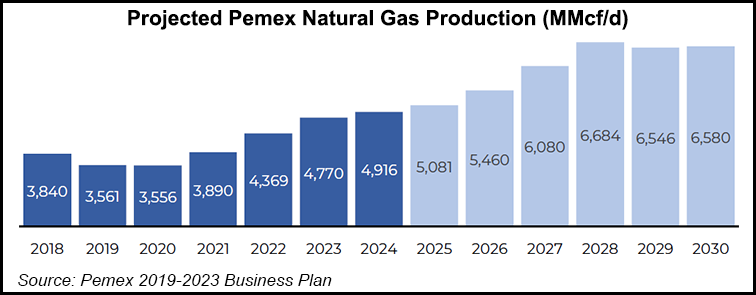

Mexico’s vision for state oil company Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex), revealed over the past few weeks in its business plan and second quarter earnings, contrasts sharply with that of its state-owned peers in Latin America.

As Pemex prepares to build an $8 billion oil refinery and revamp its existing fleet of six refineries, Brazil’s state oil company Petróleo Brasileiro (Petrobras) is in the process of divesting eight downstream assets that account for half the country’s refining capacity to focus on the more profitable exploration and production (E&P) business.

Whereas President Andrés Manuel López Obrador opposes hydraulic fracturing (fracking), Argentina’s 51% state-owned oil company, YPF SA has turned the Vaca Muerta shale formation into the first unconventional drilling story outside of North America, as evidenced by the country’s first-ever exported cargo of liquefied natural gas (LNG) in June.

Colombian national oil company Ecopetrol SA also plans to invest up to $500 billion in shale pilot programs from 2019-2021, and it is appraising two immense, deepwater natural gas discoveries off Colombia’s Caribbean coast made in 2015 and 2017 by joint venture partner Anadarko Petroleum Corp.

Pemex’s 2019-2023 business plan, which was published earlier in July, confirmed that the operator will not seek equity partnerships with fellow producers in the upstream segment, and plans to fund and oversee construction of the 340,000 b/d refinery in Dos Bocas, Tabasco.

These plans, ambitious under the best of circumstances, follow a downgrade of Pemex debt in June by Fitch Ratings debt to “junk” status, and a revision by Moody’s Investors Service of its outlook for Pemex to “negative” from “stable.”

With financial debt of $104.4 billion at the end of June, Pemex remains the world’s most indebted oil major, in large part because of its onerous tax burden.

Pemex’s “high levels of taxation mean it must issue debt, usually in international markets, to finance investment and meet its own budget requirements, as well as that of the government,” according to a paper published in mid-July by the Baker Institute for Public Policy’s Benigna C. Leiss and Adrian Duhalt.

Pemex’s rejection of joint ventures compounds the challenges posed by its crushing debt load, the researchers said.

Under López Obrador, Mexico has suspended bid rounds, farmout tenders for operating stakes in select Pemex acreage, and migrating oilfield services contracts to exploration and extraction contracts. All of these measures had been meant to inject fresh capital and expertise into Mexico’s upstream segment and to spread exploration risk to firms besides Pemex.

Oil companies these days “very seldom take 100% ownership in a project; rather, companies share risks and costs with other firms and take advantage of the technical knowledge and synergies that potential partners may bring to a project,” Leiss and Duhalt said.

The researchers cited that out of 27 conventional and unconventional oil projects in onshore, deepwater, and shallow water environments started by ExxonMobil Corp. between 2013 and 2018, the company held a 100% stake in only three, “while in all the others it had a working interest ranging from 9% to 62%.”

Pemex, meanwhile, continues “to pour expenditures” into mature shallow water fields Cantarell and Ku-Maloob-Zaap to slow the company’s declining oil production, the researchers said.

“For Pemex, the emphasis on production from existing assets results in larger expenditures per unit of production, which leads to greater debt, particularly when current revenues are not able to be redeployed for portfolio expansion and diversification.”

Upstream hydrocarbons regulator Comisión Nacional de Hidrocarburos (CNH) earlier in July approved a modified $4.9 billion development plan submitted by Pemex for the Ku field, which accounts for 4.4% of Mexico’s crude production.

Construction of the Dos Bocas oil refinery in Mexico’s Tabasco state is to begin on Thursday (Aug. 1), energy minister RocÃo Nahle said Monday. Construction of the refinery, which the government will fund entirely, is take no more than three years, Nahle said, and require “maximum” investment of $8.13 billion.

An invitation-only tender for the project’s engineering, procurement, and construction was scrapped in May after none of the invited consortiums was willing to commit to the government’s timeline and budgetary constraints.

In response, the government said Pemex and energy ministry Sener would oversee the project, whose necessity and viability has been widely questioned by analysts.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |