NGI Mexico GPI | E&P | NGI All News Access

Pemex 2019-2023 Business Plan Aims to Boost Oil Production by 1 Million b/d

Analysis Tuesday of the long-awaited publication of the 2019-2023 business plan of Mexico’s national oil company Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex) abounded in metaphors that reflected market concern over its contents.

One local newspaper headline placed Pemex and its business plan in the “eye of a storm.” Another spoke of a “coin toss” over the future of both the company and the nation’s economy.

During his regular press conference on Tuesday, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador added a metaphor of his own in an extensive preview of the plan. He said the government is “sowing oil” in the first half of his six-year administration by sharply reducing the tax burden on Pemex. A rich harvest can be expected for the second half, he added.

Pemex CEO Octavio Romero Oropeza said during the press conference the plan reduces the profit sharing tax on the company to 54% from 65%. The change should amount to savings of $7.1 billion for Pemex over the course of the next two years.

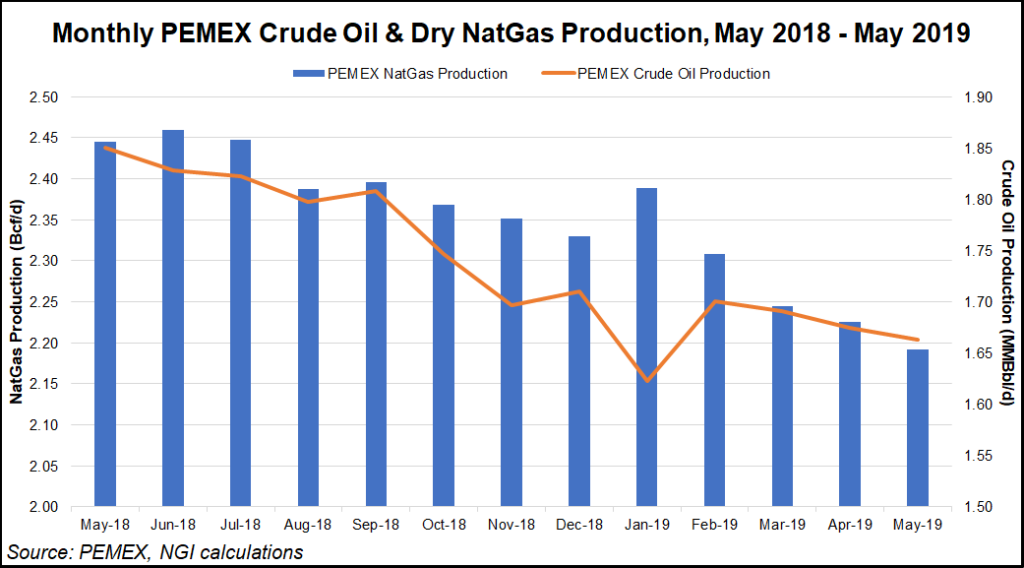

The plan also calls for crude production to reach 2.7 million b/d in 2024, a level not reached since 2008 and an increase of about 1 million b/d on current production.

“We’re going to rescue Pemex, along with its workers and it’s technicians,” López Obrador said. “There’s no question of there having been any resistance. The workers, the company’s pensioners, those with long-term contracts and others on temporary stays, technicians, engineers, all backed the plan.”

Romero pledged to “turbo-charge” production at Pemex. “We’re aiming to slash the times between new discoveries and first fruits of the new fields.”

The upstream emphasis would be on onshore and shallow-water fields. The deepwater strategies of previous governments led to little success, Romero said. “Between 2011 and 2018, about 45% of Pemex exploration was in deepwater projects that so far have yet to produce a single barrel of crude.”

Romero said the plan called for the gradual recovery of refining capacity based on “larger amounts of investment” in the rehabilitation of the six refineries and the development of the Dos Bocas refinery.

“The presentation had no surprises in it, and at least some surprises were needed,” said Energía a Debate editor David Shields. “Once again they appear to have rejected proposals for farmouts.”

Analysts have proposed farmouts as a way of boosting the company’s production and earnings.

“They’re sticking to their guns” on exploration and production “and on the issue of the refinery, and there’s no great profitability in either,” Shields said “It’s not even clear to me that there is going to be an increase in oil output or that they will build a refinery.”

The reduction in the Pemex tax burden “could turn out to be a waste of public money,” he added.

Consultant Luis Miguel Labardini, a partner in Mexico City-based Marcos y Asociados noted the potential of López Obrador’s announcement of 18 new 25-year integral oilfield service (OFS) contracts.

Integral OFS contracts, many of them including incentives, have been used previously by Pemex, most recently during the administration of Felipe Calderón, president from 2006 to 2012. “But the length of the new contracts indicates that they are for field development, and that is an area where Mexican contractors have little or no experience,” Labardini said.

“As a result, Mexican service companies will be looking to form associations with experienced foreign companies that have plenty of knowledge of field development.”

The Pemex business plan, unanimously approved by the board, is more than 200 pages long and is expected to be published later this week.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 |